Candace Williams: The Art of Looking

Poet Candace Williams talks about how her dog Madonna has influenced her writing, what a poet's job is, and how observation and documentation can be a radical act.

There are 3 million reasons to admire Candace Williams (though this is a rough estimate – let's allow for a deviation of plus or minus two percent), but I want to focus on one today: her watchful eye. It's evident in her poetry and in her care for her rescue pit bull Madonna. It's all over this interview, and I want to celebrate it.

On her walks with Madonna around Crown Heights, Candace's eye is tuned to her surroundings. She notices "the routines and residue," the history of trauma and oppression that hide behind the shiny veneer of recent development. In her poetry and life, Candace does the necessary work of observing – and hopefully, we are smart enough to take notice, too.

Before we hear Candace talk about Madonna, class, routine, and self-care, here's a little background: Candace Williams is a black, queer nerd leading a double life. By day, she’s head of community operations of a podcasting startup. By subway ride and lunch break, she’s a poet. She's a Brooklyn Poets Fellow and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Sixth Finch, Lambda Literary Review, Bennington Review, Copper Nickel, No, Dear, and elsewhere.

In a two-night run of Ghetto Hors D’oeuvres: COLORS, she collaborated with music, theater, and film artists to perform “Crown Heights” and “Commute” on stage. She’s been a featured reader at the New York City Poetry Festival Couplet reading, Union Square Slam, and other events.

In a past life, Candace was a K-5 science, robotics and comic book writing teacher in the South Bronx. She earned her MA in Elementary Education from Stanford University and graduated cum laude with a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) from Claremont McKenna College. She's participated in Cave Canem and Brooklyn Poets workshops. On an average day, you’ll find her cuddling her pit bull Madonna and tweeting a little too often.

Tell me about how Madonna came into your life.

Madonna was rescued from a church basement by the ASPCA. She spent the first three years of her life there and then had to stay with the ASPCA for close to a year so they could treat her heartworm and start to alleviate some of her anxiety. She was incredibly fearful of humans (she would cower under furniture and couldn't go outside).

At first, they didn't think I should take her because she would be my first dog. After about seven hours of looking at other dogs and talking to their behaviorists, they let me take her.

It was pretty rocky at first. She wouldn't go outside at all and was very afraid of me. I learned how to do clicker training and got her to touch my hand and go to her crate. Once she had that safe space and a way to choose to explore new places with me, the training was a bit easier. She went outside with me for the first time four weeks after I adopted her. Now, she's a much happier dog. She even spends time swimming, hiking, and playing with other dogs at a dog camp when I travel.

Confession: I’ve never been more grateful for an Instagram hashtag than I am for this one: #madonnatherescuepitbull. Your love for Madonna is evident even in the way you photograph her – you can tell she’s never far from your side. What moves you to chronicle this relationship?

Looking is an important and radical act. I peer at and write about personal and social trauma. I’ve realized it’s just as important to document comfort and joy. Also, SHE’S SO CUTE!

“Looking is an important and radical act.”

Candace and Madonna

Let’s talk about your poem “Crown Heights” where Madonna makes a cameo:

…She puts

her pit bull into coat and boots. They do

their morning routine—heading west on Crown

to Rogers; turning right and buying sweets

near President; going east to Nostrand

and walking back to Crown. She walks the heart

of Crown Heights. She walks the ghost perimeter

of Crow Hill Castle—named after murders

of crows that flocked to trees atop the hill;

or darkies lined up on the hill like crows;

or the louring inmates dressed in crow black.

You mentioned in our pre-interview banter that Madonna’s presence here has “links to class, comfort, and routine.” Would you elaborate on these ideas?

I made the decision to adopt Madonna when I achieved stability in Brooklyn. She adds a lot of structure to my life and anchors my decision-making (I spend less nights out and about and more nights reading in bed). I wanted my first poem about Crow Hill Castle to compare my privilege and comfort to the horrors that happened where I now live, sleep, and walk Madonna.

That walk you take with Madonna in “Crown Heights” gives you the opportunity to, as you said, “transport my audience to Crow Hill Castle,” the site of a former penitentiary in Brooklyn. It’s a craft choice that feels so necessary when talking about the history of a place and how gentrification tries to pave over that history. So my question is this:

True or false: it’s a poem’s job to gets its readers’ hands dirty.

False. The only person that can get readers’ hands dirty are readers themselves. One of my jobs as a poet is to spark curiosity in my readers so they attend to what’s on the page and integrate that experience into their conscious life.

“One of my jobs as a poet is to spark curiosity in my readers so they attend to what’s on the page and integrate that experience into their conscious life.”

Photo courtesy of Eva's Play Pups Countryside Dog Camp

In addition to “Crown Heights,” your poem “John Henry Suffering and Dying in the Arms of His Polly Ann After a Ventricular Rupture Resulting from Overwork” is also written in blank verse. A taste for our readers:

I drove through slag and ore so men could move

the Coosa Mountain, God not seen. I fought and won

and found no prize because this work is not the will of God.

The will of God is not the greed of gluttons—masters who

are now the captains….

What draws you to this form, and when do you decide whether or not to tackle a poem in blank verse?

I wrote “Black Sonnet,” “Crown Heights,” and “John Henry Suffering…” in March while I participating in two concurrent workshops with Jason Koo— Blank Verse at Brooklyn Poets and Fast Break: Capturing the Motion of the Mind at Cave Canem. I think blank verse is good for hitching the reader on your back as you push through a thought, memory, or scene.

I’ve always loved the narrative momentum of Shakespeare’s dramatic monologues and the gravity of Robert Hayden’s “Middle Passage.” I had been researching John Henry and Crow Hill Castle for months and couldn’t find the right form for my first works about these somber, sprawling subjects. I’m still experimenting with blank verse and figuring out when it does and doesn’t work.

“Blank verse is good for hitching the reader on your back as you push through a thought, memory, or scene.”

Photo courtesy of Eva's Play Pups Countryside Dog Camp

I want to talk about “Black Sonnet” because I deeply love this poem. A couple lines:

I make the right slight right and I’m still black.

I ring the bell twice and I’m still black.

My love smiles with her eyes and I’m still black.

We kick it for a bit and I’m still black.

I turn off all the lights and I’m still black.

Can you talk a little about the choice to set up moving through daily life and being black as a dichotomy?

I used anaphora and meter to create a sense of inevitability and exasperation. I wanted to show that folks under siege accumulate privileges and accomplishments but still pay a tax for our identities. Little Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Rekia Boyd, and Islan Nettles paid the ultimate price. I’ve been stopped and frisked in Chelsea while wearing a bow tie and suit. I’ve been followed on the streets of New York, New Delhi, and Xi’an. I’ve looked a little too queer on Nostrand. Too black to be that “kind, well-spoken person on the phone.” Too black to spend a day at my coworking space without people asking, “Can you clean the bathroom/office/kitchen when you get a chance?”

“Folks under siege accumulate privileges and accomplishments but still pay a tax for our identities.”

Candace and Madonna

What poetry projects are you working on now?

I’m collaborating with printmaker Laimah Osman on a “Black Sonnet” broadside. I just finished a chapbook manuscript and am developing a full-length work. I’ve started the process of documenting official and community monuments in Crown Heights—everything from street signs to statues and dangling sneakers. I’d like to explore the monuments that have been built and the ones we haven’t built yet. I’m collaborating with a film and performance artist to imagine more monuments. I’d like to invite my neighbors to participate as well.

Back to Madonna – has your writing process changed since taking her in?

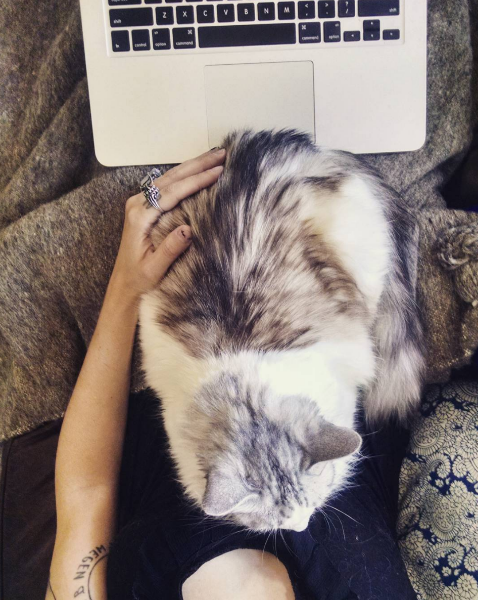

I didn’t start writing poetry until after I took in Madonna (fall 2015). Adopting Madonna helped me have a sense of emotional comfort that allows me to see, process, and write. She snoozes next to me while I write poems and is very attentive audience when I read them aloud. Taking care of Madonna is part of my self-care regimen. Without her, it would be hard to create the intellectual and emotional space to write.

“Taking care of Madonna is part of my self-care regimen. Without her, it would be hard to create the intellectual and emotional space to write.”

Has caring for Madonna changed the way you see or interact with the world? If so, how does that translate into your poetry?

Before I adopted Madonna, I spent more time out and about in the city. She anchors me at home. It’s why I’ve started to explore Crown Heights in my research and work. I spend more time walking the streets of Crown Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Flatbush. I notice the routines and residue.

Fill in the blank: Madonna is most likely to appear in a poem about…

Peanut butter. Or cream cheese.

A simile for Madonna?

Madonna is chicken like chicken.

Jess Feldman: Carry the Wild

Jess Feldman talks about how her cat Willicus helped buoy her through a difficult year and offers writers who work that 9-to-5 hustle some pointers on finding and maintaining creative space for poetry.

Fact: today you'll learn why Jess Feldman doesn't care much for llamas (spoiler alert: they have a v. annoying superpower), the connective thread between Frank O'Hara and her cat Willicus, and her sage advice for melding the 9-to-5 world with the creative life.

Teasers aside, what a joy it is to talk to a poet who is so mindful in the way she moves through her environment. Perhaps that's why she is both a poet and a quilter – both arts require the endurance to advance stitch by stitch.

Before we get to it, a little background: Jess Feldman is a writer, editor, and third-generation quilter originally from New England and now based in New York City. Her manuscript Call It a Premonition was chosen by poet Zachary Schomburg as winner of BOAAT’s 2015 Winter Chapbook Prize, and her poetry has appeared in numerous publications, such as Sixth Finch, Transom, The Portland Review, Vinyl and Tuesday; An Art Project. She holds an MFA in writing and a BA in English from the University of New Hampshire, and currently works as the office manager at a boutique entertainment law firm in Brooklyn.

Let’s hear a little background on your cat Willicus. What a name!

First off, the name breakdown: Matilda > Tilly > Tilly-Will > the Willicus. Purrfect sense, right?

I've had my cat for nearly seven years now (she'll be seven in September – a Virgo / Libra cusp). My partner Mike Luz & I have been together for nearly nine years, and I can't believe that for those first years we didn't have our cat Tilly "the Willicus." How did we survive?!

Willicus is a mere eight pounds, loves salmon & destroying things slightly, and despises cylinders (specifically my round hair-dryer brush). I always saw myself as a dog- & horse-person, but isn't it wonderful to continue to live & find out how truly big and ever-expanding the heart can be? There are so many cool, amazing creatures out there to inspire love & compassion in humankind.

But to be honest, there is one furry creature I don't particularly like and that's llamas. The llamas I've met don't really acknowledge your presence. Instead they emit a high-pitched noise while slowly backing away – I believe that if you were to sustain that llama noise in a direct hit, your entire being would be eliminated off the face of the planet. However, I did see something about a therapy llama named Rojo who may be able to change my mind. Like I said, my heart could hold love for a llama someday.

Back to my cat…

I picked up the Willicus on a chilly, dark night in November 2009. She was one of two kittens left and was raised by a woman who lived in the New Hampshire woods. Willicus's dad was a feral cat of the woods, which is why she's still kind of half-feral (or as Mike & I say: half-domesticated). I told myself the first kitten to walk over to me would be my cat, and that's the Willicus for you – she's bold even when she's scared or uncertain. When I was driving her back to my apartment, she somehow wriggled her way free of the soft cat-carrier I had in my car and made her way onto the seat next to me. #copilot4life

2009 was a difficult year for me. This scrap of a tabby cat sauntering into my life with her sassy strength & take-no-holds approach to enjoying life buoyed me. She continues to be a source of inspiration to me when I feel besieged by the world and its demands. Her talents for napping and playing with junk (elastic bands, tissue paper, plastic bags) help me find balance in the here & now when so often I get tied up in my mental & emotional maelstrom. Willicus is the antidote to world-weariness.

"Willicus is the antidote to world-weariness."

That’s been true for me, too – animals seem to sustain my emotional endurance. Sometimes I’ll look up from my work in full existential-crisis mode and think, I can’t do this for another minute, and then Pete or Bear will look at me with their funny little faces and their sweet eyes, and I’m like, okay, do it so you can buy dog food. That pragmatic motivation that comes with caretaking can be so essential for the minute-to-minute existence, right?

Definitely. It’s a relief to get out of my head in those moments, and it’s a gift to be beholden to something that’s perpetually adorable.

You write for a living now, correct? My experience says that word work (at times) can be mentally exhausting in uncharted ways! What’s your experience been like? And how do you compartmentalize / reserve creative energy for your poetry work?

I do more editing and curating of material now, but no matter what, I use my work experiences as opportunities to gain new language (structure, concepts, diction) that I can fold into my own work. In essence, poet-brain is on all the time for me. Poet David Rivard got me into the habit of tagging good words, ideas, etc. into a small Moleskine. It helps me keep the chaos anchored somewhere and feel productive even if I haven’t had a moment to pull together a complete poem.

Living the 9 - 5 office life at times can feel like I’ll never get any good writing done. Instead of seated somewhere picturesque and quiet with pen & paper, I’m answering phones and emails. In those moments, I remind myself that poems don’t just live in vacationland. Poems live in that mundane free-for-all of our inner & outer lives. They may not look like much at first, but brush them off and they shine.

"I remind myself that poems don’t just live in vacationland. Poems live in that mundane free-for-all of our inner & outer lives."

On to poems! My nerd heart is so happy that you write a lot about animals. Let’s talk about one poem in particular – “Hinterland” – a poem you described as your “calling-all-animals / New-Hampshire-girl manifesto.” For our readers, a few lines:

Crowded with light, am I so grave that what were once maned wolves are now purple

asters?

Are ladles as stiff, as accurate as a flock of hooded merganser?

I have never been a person in the world with hands held out, anticipating Communion.

I have not been that honest.

You, bright helix: Touch; tell this touch I am far from things I knew.

How important are animals in telling the story of a place? In telling the story of what matters to you?

Growing up, the woods were my haven. It was a place I could go to and feel wild & lonely in the most productive way. I’d follow tracks, catch tadpoles, collect empty buckshot canisters, climb trees, sing songs mournfully, set snares that never worked – the whole kid-in-the-woods gamut. Animals both seen & unseen were points of inspiration, things to dream upon, and sometimes, beings to become.

As Sarah Orne Jewett so rightly states in her novella The Country of the Pointed Firs, “In the life of each of us… there is a place remote and islanded; we are each the unaccompanied hermit and recluse of an hour or a day; we understand our fellows of the cell to whatever age of history they may belong.” I carry that wild space inside me still. It feels especially important now since I’m surrounded by more buildings than trees these days.

However, a few words about the city wilderness I’m experiencing now: I never thought I’d like living in New York City, but after three years, it’s become it’s own wild place I inhabit with love. There’s a different sort of wildlife here (rats, cockroaches, pigeons & feisty sparrows, tiny dogs, alley cats) that I’m interacting with and integrating into my new work.

"Animals both seen & unseen were points of inspiration, things to dream upon, and sometimes, beings to become."

Your chapbook Call It a Premonition is based on the Voynich Manuscript, a Renaissance-era text that to this day hasn’t been deciphered, much to the chagrin of linguists, cryptographers, and codebreakers. How did you settle on the interpretation of the manuscript as a collection of mini, experimental dispatches?

I had this teenage girl voice entering my poems for a while. Stumbling upon the Voynich Manuscript (which you can page through via Yale) seemed like a great opportunity to explore that teenage girl voice, reimagining the Voynich Manuscript as her diary. I had just gotten my first smartphone and was managing social media for a hunting & fishing app at the time, so my new awareness of digital presence enters the chapbook alongside this beloved yet nameless girl’s coming-of-age.

In your poem “The Way Back,” a horse “steady in the depths of his soft manured stall” finds a place in a poem steeped in loss. Why did you choose the horse to mirror the speaker’s pain?

I love horses. They are my favorite animal and have been my favorite animal since I can remember. As a kid, I wanted to grow up to be a horse instead of an adult. Instead I grew up to be an adult that stables a horse in any poem she can. I have immense respect for a horse’s perceptive powers. I’ve always seen them as healers; in poems and in real life, their beings are strong enough to act as a conduit for a person’s true feelings.

"I carry that wild space inside me still."

Back to dear Willicus. I know you said you are too close to her to write about her yet, but has she helped you write about the animals that do appear in your poems?

I so want to write a poem about Willicus, but it’s tricky for me to focus a poem on her. It’s like I’ve gotta build up my heart-vulnerability chops in order to capture her on the page. With the other animals that appear in my poems, there’s a distance there which allows me to manipulate them. They are what I imagine them to be. Willicus defies imagination.

Have you read a poem written by someone else that reminded you of Willicus?

Such a great but tough question! I think Frank O’Hara’s poem for V.R. Lang captures something of my love for Willicus and her formidable spirit.

"It’s like I’ve gotta build up my heart-vulnerability chops in order to capture her on the page."

What’s next for you on the poetry front? (More menageries, I hope!)

I’ve been working on a chapbook-length manuscript called “Body Mind” that investigates my relationship to the body. These poems are doing work to ground me (at least momentarily) back into the toes and fingers and guts and sex of a woman-person interacting with other persons. It’s been a challenge but a necessary one. One of the poems from this manuscript just found a home at Sixth Finch, and a few more will soon be out in Paperbag. And don’t worry – there are plenty of animals in these new poems!

A simile for Willicus?

She’s a light for all times.

Sonya Vatomsky: Hierarchify Your Love

Poet Sonya Vatomky talks about how their companion Magpie Underfoot helps them write and survive.

It's hard not to fangirl over Sonya Vatomsky, gothy, cat-loving, say-anything poet with a must-follow Instagram feed and a penchant for concision. So I will cosign myself to saying this: I could've probably asked Sonya any boring question and their response would've been interesting. That's just who they are.

But fear not, dear reader – I didn't put that theory to the test. I talked to Sonya about their painfully cute companion Magpie Underfoot and how this cat helps Sonya write and survive.

A little about Sonya before we hop to it: they are a Russian American non-binary artist with too many feelings on the inside and too much cat hair on the outside. They are the author of Salt Is For Curing (Sator Press, 2015), a debut poetry collection about bones, dill, and survival, as well as one chapbook. Poems, essays, and interviews have appeared in Dirge Magazine, Entropy Magazine, The Hairpin, Lodown Magazine, VIDA, The Poetry Foundation, and other publications. They live in Seattle with their cat, Magpie Underfoot, and a growing collection of taxidermy, wet specimens, and other oddities.

[CW: sexual assault]

Your cat has the coolest name. What inspired it?

Thank you! She’s named after the recurring symbolism of the magpie in 80s progressive rock band Marillion’s lyrics. “Underfoot” was added later after our vet called her “Magpie Vatomsky” — she doesn’t strike me as the kind of cat who would take someone else’s last name.

You mention that you adopted Magpie Underfoot from the shelter and she was "horrifically underweight." Can you talk about the process of caring for her in those early months and what impact it had on your relationship with her?

She fattened back up to normal quickly so that wasn’t really an issue, but whatever her life was like before the shelter left its mark. The first six months I had her, she’d meow me awake at 4 a.m. and meow the entire time I was at work. I almost had to move! She still gets really pissy when she can see the bottom of her food bowl; she has a little plastic bow she carries around and places in her food dish when she’s dissatisfied with it. It’s from a Christmas like 3 years ago but is so funny I don’t throw it out.

“She doesn’t strike me as the kind of cat who would take someone else’s last name.”

In our pre-interview chat, you said Magpie Underfoot is "more like an emotional support source without which most of my writing wouldn't happen." That made me remember your interview with Maudlin House when you said Salt Is for Curing is about "exorcising my demons – literal demons, literal exorcisms." I'm thinking there's a connective thread here – did Magpie Underfoot's emotional support help make those exorcisms possible?

Yes, absolutely. Around when the catalyst for my book happened — actually, I’m just going to be blunt here. I got assaulted by a friend of a friend after a party, and in the month or so around that, I also started taking antidepressants, had a horrific breakup, and needed a medical procedure that really stressed me out so I was basically a shitshow. Magpie, who normally slept by my feet, started sleeping on the pillow next to me. She still does that. I put both arms around her and my nose in her fur.

You described what I'm going to call "love transference" in your poetry, where you're writing about one subject, but channeling feelings you have for another. And I love how you put this to use in "Valerian Tea," a poem you said is "some kind of weirdo hybrid love poem about her [Magpie Underfoot] and my partner." (For our readers, a taste: "this interconnected belonging where our / eyelashes braid together and I fossilize with you and die / tomorrow and live forever and my face feels like my face…") How has Magpie complicated your understanding of what love is?

I don’t think she’s complicated it. Every once in a while my brain does the thing where I NEED TO HIERARCHIFY ALL MY LOVES and I’m like, is it reasonable for a cat to be this important? But she is, so whatever.

“Every once in a while my brain does the thing where I NEED TO HIERARCHIFY ALL MY LOVES and I’m like, is it reasonable for a cat to be this important? But she is, so whatever.”

Not a question about animals, but a question about being a human animal. How has identifying as non-binary influenced your work? I'm thinking specifically about Salt's meditations on what it means to occupy space in a patriarchal world.

At the time that I was writing Salt, I felt very female. It’s actually the only time in my life I’ve felt that way and it was in the aftermath of a sexual assault — like a man stamped WOMAN on my brow. To be so viscerally read as a woman after a lifetime of feeling inadequate was a bit of a journey, for sure. I started coming out as non-binary around when Salt got the publication offer and was worried that would be weird somehow, but it hasn’t been.

Tell me about your writing process. Do you have a ritual or schedule you follow? Does the poem start with an idea or a line? Is Magpie nearby?

No ritual or schedule, but I do prefer to write at home and my apartment is tiny so she’s definitely nearby and trying to sit on my laptop.

“To be so viscerally read as a woman after a lifetime of feeling inadequate was a bit of a journey, for sure.”

Salt is full of references to the body – specifically, the human and animal body as meat, fitting for a collection that uses food as a device to explore power dynamics and to dissect the self. But I want to focus on a specific animal – the fish in "Spidersilk" ("You looked so far away, I felt crazed; gutted myself like / a fish and dug in") and in "Herring under a fur coat" ("I put my coat on. Under, I / am cold wet fish, scales and weights, / I am wide maw and narrow fin"). Why did you choose the fish to name the vulnerability in these poems?

This isn’t that philosophical, but a fish is basically the only animal your average home cook is going to gut, yeah? I wanted the gutting to feel messy and vulnerable but not add any extra context, like using a deer or a rabbit might have. “Herring under a fur coat” is actually just the translated name of a Russian salad, which is why that poem also has all those beet and potato and mayonnaise bits.

True or false: poetry is a kind of spell work.

Definitely.

A poem with an animal in it (metaphorical or otherwise) that you wish you'd written?

I’ve been writing a lot about whales recently, even though I kind of dodged that fish question up above. I guess it would be another sea creature. I’m really fascinated by how little we know of the deep sea, the animals that live there.

“A fish is basically the only animal your average home cook is going to gut, yeah?”

A simile for Magpie Underfoot?

A little lemon. She is so sour. I love it.

James Dunlap: The Briefness of the World

James Dunlap on why art is an inevitable byproduct of dog companionship and how caring for animals taught him how to engage with his father.

Sometimes I'm good at giving advice, so let this be an example: keep your eyes on James Dunlap. If his body of work so far is any indication, he's poised to do incredible things throughout his poetry career. And I'm not just saying that because he's a gold-hearted dog owner, though that certainly doesn't hurt. When he talks about his dog Sadie, you can almost see the world getting a little brighter. It would be a shame to keep that all to myself, so check out James' thoughts on how dogs teach us to love with abandon, how art is an inevitable byproduct of dog companionship, and how caring for animals taught him about his father.

Before we get going, a little about James: he's a poet from Morrilton, Arkansas, and has studied English and creative writing at University of Arkansas and Southern Illinois University Carbondale. His work has appeared in Nashville Review, storySouth, KYSO Flash, Dirty Napkin, Weave, and Heron Tree. He lives with his Jack Russell terrier Sadie.

![IMG_1476[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56d23451d51cd456e60ad697/1467657452253-EC96F3IYL43ZC1W9OI1K/IMG_1476%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_1483[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56d23451d51cd456e60ad697/1467657449491-ICYHS3WF89V7PZ8C3Y6H/IMG_1483%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_2177[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56d23451d51cd456e60ad697/1467657450585-WPIBRK7G1P6TMJ6PY70F/IMG_2177%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_2461[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56d23451d51cd456e60ad697/1467657452554-PMADZVQ462R09QGWONS8/IMG_2461%5B1%5D.JPG)

Let's talk about your dog Sadie. How did she come into your life?

About eleven year ago, my older sister moved in with my parents and me for a little while. She brought with her little bottle rocket of a dog named Sadie. My sister eventually moved somewhere where she couldn’t have dogs and left us with Sadie and a rat terrier named Dixie.

I’ve always had trouble sleeping for as long as I can remember. Some nights when the air in the house grew thick and unbearable, I would take long walks or sit outside or lay down in the living room where we kept the big fan. Nights like that I would find Sadie on the couch and I would dip us a bowl of ice cream or we would share some chips. After a while, she started sleeping in my bed. Soon she began waiting up for me, sitting in my lap while I read, sometimes pawing at the page if she got too tired. She stayed with me any time I was laid up sick and always greets me when I come home. This is how she became my dog.

What makes Sadie different from the dogs you grew up with as a kid?

We grew up out in the country, and between dogs roaming around and people dropping them off, so many dogs came in and out of my life. I loved them all. But I always knew in the back of my mind that they were transient. I knew that they would be moving on one way or the other and that there would always be another dog to fill the void.

It’s not like that with Sadie. It’s going to hurt something awful when she dies. I won’t just tuck my hands in my pockets, look down and say, well, and move on. I’ve seen her grow from a pup into an ornery old lady that tip toes in rain puddles to not get too wet.

In our pre-interview banter, you said that Sadie taught you “how to attend the briefness of the world.” I love that – can you elaborate?

I think there is something moving about people loving things that will go away. The most you get with a dog is seventeen years, if you are lucky. If you raise a dog right, you’ll learn a thing or two. I think you learn a lot about humanity. There seems to be very few reasons to have a dog beyond love and companionship. I think it's easier to love a dog than it is a human. A dog never dredges up fear of rejection, never makes you feel ashamed or inferior. You can love a dog with abandon and you must because they don’t have time for anything less.

“You can love a dog with abandon and you must because they don’t have time for anything less.”

Shifting gears a little: you mentioned that you lived in the country when you were young, and your family raised rabbits to sell and to eat. You said you would get attached and see them as pets. As someone who has two pet rabbits, I can imagine how difficult this must have been for you. Has this informed how or why you write about animals in your poems?

That’s nice; I hear rabbits make good pets. I think so much of my writing concerns itself with the ephemeral nature of relationships. I think this is most true when I’m writing about my father. And our closeness is a strange one. I love him. He’s taught me many things. But there seems to have always been a disconnect. It’s almost like building a house on an uneven foundation. You keep re-squaring the frame, but cracks keep showing up.

My relationship to our rabbits was incredibly ephemeral. I would create these bonds, then break the bonds myself. So I think that I often connect my relationships with humans to those I have with animals and that bleeds into my writing. It would be fair to say I’m haunted by my family at times, and I can’t stop writing about it. So there’s this amalgam of animal, landscape, and family that rule my poems.

In your poem “Boy,” the narrator's father burns a rocking horse and seems disgusted when the (presumably young) narrator cries. Is it fair to say that the animals in your poems (both symbolic and real) help illuminate the dissonance in your relationships with your father and grandfather, especially where masculinity is concerned?

That’s a very nice insight. Thank you for reading my work so closely. I think you are definitely right. My childhood was spent around animals and around my dad. As I learned about caring for animals, even harvesting them for food, I was really learning about him and how he related to me or failed to relate to me.

There was a lot of emphasis put on masculinity. For the longest time I thought my father had penned the phrase, “Stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about.” There was an aggregate of things that he thought make a man a man. A man works with his hands. A man doesn’t cotton much to crying. A man never backs down and takes what he wants. My father was some sort of hillbilly Nietzsche.

So animals, when they appear around me and my father or me and my grandpa, do shine a light on our brokenness. It would come through other ways, I suppose, but since I learned so much through animals, they will always contain the shards of our relationships.

“Animals, when they appear around me and my father or me and my grandpa, do shine a light on our brokenness.”

You mentioned that you're too close to Sadie to write about her yet, but has she influenced your poems or writing process in less overt ways?

She can be insistent when you ignore her (read as: work), so managing time becomes important. She is not beyond jumping on my book or pawing my face. She’s taught me to focus when I have a task and not much time. And I think it just helps having an animal around. She helps get my mind off poems for long enough to refocus. Poems take a long time and Sadie was always around to teach me patience. You can never overestimate a silent companion for writing.

What writing projects are you working on now?

I am working to complete a full-length collection. I think this book will end up being more of mixed-tape type collection, but with the same speaker (me).

What's your favorite poem about a dog, and why do you think poets are so fascinated and drawn to this animal?

I think today my favorite dog poem is “The Black Dog of Blue Ridge” by Elizabeth Hadaway. It has so many things I love about poetry. There is a ghost dog, family tension, it walks the line of lyric and narrative. It’s a great poem in her book Fire Baton (University of Arkansas Press).

Poets have been charged with the task of chronicling the human experience. We know that 15,000 years ago, dogs were wolves. What began as a utilitarian exercise in sanitation and hunting technology became a companionship and occasional obsession. You can’t oversee the development and evolution of a living thing without forming attachments, and ours is a life-giving attachment.

Flaubert said the poet’s life is a dog’s life. Granted, he meant to say it is a rough life, but I see a few parallels, mostly in curiosity and a tendency to come up with a few ticks.

“Flaubert said the poet’s life is a dog’s life. Granted, he meant to say it is a rough life, but I see a few parallels, mostly in curiosity and a tendency to come up with a few ticks.”

A simile for Sadie?

This is by far the hardest to answer. I said I never write about Sadie. I have tried before—a poem about squirrel hunting. Jack Russel terriers were originally bred as squirrel and rabbit hunters. Here is a simile that can never live up to her: See her lighting through the backwoods like a haint made of starlight and ash.

Rachel Mennies: Interrogating Our Animalness

Rachel Mennies talks about the subtle and dynamic ways her dog Otto has shifted her worldview, his wagging presence in and around her poems, and how animals help us understand ourselves.

If you know Rachel Mennies, you don't need me to tell you she's a triple threat of smarts, talent, and generosity. If you don't know her, have a seat, dear reader, and prepare to hand over your heart, silver platter and all. There's perhaps nothing more rewarding than listening to a poet discuss something they deeply love, and for Rachel, that's her dog Otto. She talks about how he came into her life, both the subtle and dynamic ways he's shifted her worldview, his steady presence in and around her poems, and how animals help us understand ourselves.

Before we get to it, a little about Rachel: She's the author of The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards (Texas Tech University Press, 2014), winner of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry, and the chapbook No Silence in the Fields (Blue Hour Press, 2012). Her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Poet Lore, Indiana Review, Black Warrior Review, and other literary journals. She is the series editor (2015-) for the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize at Texas Tech University Press, she teaches in the First-Year Writing Program at Carnegie Mellon University, and she is a member of the editorial staff at AGNI. She lives in Pittsburgh with her dear pup Otto.

How did Otto come into your life?

About three years ago, my husband and I decided to tackle the responsibility of dog ownership, after wanting a dog for many years prior. Moving from that general decision to the specific decision of which dog to adopt—we went the rescue route—was the hardest part of the process. The days spent on Petfinder meant reading one heart-tugging story after another, especially knowing we could only take on one dog and, since we have an apartment with no yard, had to choose a dog carefully that could handle our city-living situation. After all the reading, we went to exactly one shelter and Otto, an Italian greyhound-beagle-other mix who was about four months old at the time, was the second dog we walked. We brought him home the next day.

Did you grow up with pets or was getting a dog a brave new world for you?

My parents got our first dachshund, Maddie, when I was a senior in high school, so I spent most of my time at home without a dog in the house. They now have two sibling dachshunds—Sammie is from the same parents, but a different litter than Maddie—and Otto plays with them as much as Maddie and Sam will allow it when I come home to visit. Because Maddie arrived right as I was preparing to leave home, I participated very little in her dog-care routine—Otto’s mostly “brave new world” territory for me.

“We’re both habit-seekers, and we’ve learned each other’s routines quite well at this point.”

Tell me a story that gives a good snapshot of your relationship with Otto.

As Otto’s gotten older—he’s three now, so no longer a puppy—he sleeps for longer and longer into the day, while I’m a true morning person. He usually pads into my “office,” the room in our apartment that holds my desk and yoga mat and the best natural light (and a plant, if I’ve managed not to kill it), an hour or so past once I’ve made coffee and begun to work, and he sets his head on my knee to let me know he’d like to go outside. We’re both habit-seekers, and we’ve learned each other’s routines quite well at this point.

You mention how Otto's schedule helps keep your writing life structured in your blog post "Poetry on The Animal Calendar" for the Tahoma Literary Review. (Oh, how we live and die by the dog schedule in my house.) I'm fascinated by this very practical and direct way he's influenced your writing process. Other than the built-in time blocking (bonafide productivity hack: get a dog!), are there other ways Otto's presence has helped you write poems?

I think often about the depth of affection a human earns from a dog once the relationship’s had some time to grow: Otto seeks my presence and time and touch so much in exchange for what to me seems like very little (food, water, shelter, predictable and consistent kindness). The bond helps me write because it exists dependably and without question—often the opposite of how I feel in terms of the writing process.

Otto and I had to earn this slowly in each other, which may also be familiar to other rescue-dog owners. The first month we adopted Otto, which also happened to be the first month of my fall semester, he growled at us from under our couch (thankfully, he’s outgrown being able to fit under there…), destroyed a few of our belongings, pulled hard away from me on his leash, and fought to get out of his crate daily. He almost escaped from our car at the animal shelter. He had no idea who we were, where he’d gone, or why we’d brought him to us. I thought for the first month that I couldn’t handle dog ownership.

But the semester continued, and he calmed down, and I found that he became the calmest when I sat beside him on the couch, each of us on a separate cushion, and I took out my computer and wrote (or graded papers). With time, he eased closer; now, if I write on the couch, he stretches out long between my legs and the couch’s back, burrowed in as close as possible. If I snap the laptop closed, he thinks it’s time for a walk. His calmness and affection feel sanctioning, especially in the many moments that I find the writing process difficult or anxiety producing. Sometimes I read drafts aloud to him, which is a comfort, too.

“The bond helps me write because it exists dependably and without question—often the opposite of how I feel in terms of the writing process.”

We've got to talk about "Elegy with Attack Dog," a poem I will remember as long as I'm on this green earth, especially the closing lines: "And you lie awake / and stare at the loss, rubbing / the soft spot at your throat / that misses the shape / of its mouth." I love the metaphor of the dog to illustrate the mechanics of grief. Can you talk a little about the inspiration behind that?

A couple of summers ago, two friends of ours had taken their own two dogs out for a run when a neighborhood dog broke from his yard and attacked all four of them. It’s a long and sad story, but at the end of it, only one of their dogs survived, and Animal Control eventually euthanized the “attack dog.”

As a dog lover, stories like these—in which the creature we love, that we let sleep in our beds and eat from our tables, bares its teeth and reminds us of its power to destroy—are especially difficult to process. In the specific grief I felt for my friends, I began thinking about the fear the incident left behind in me (that whole summer, each dog that ran up to Otto at the park or on the street made my pulse elevate) as a metaphor for a broader sense of loss—how long it takes, if ever, to pass through the process of grief into permanent safety or calm.

I moved practically from these thoughts into a draft of “Elegy…” in a writing workshop I was spying on that was led by the poet Jill Khoury—we were teaching in a Young Writers program together at the time—who had tasked the high-schoolers with writing a poem that utilized anaphora. I started with the specifics I remembered of my friends’ attack—the dog going for their dog’s neck, and holding on—and the poem unfolded slowly from there.

Let's talk about the non-metaphorical dogs and animals that show up in your poems. Why do you think animals have such a prominent place in poetry at large and in yours in particular?

I write often about the human body and its animal-feeling; I wonder if some of our writing about animals comes partially from our desire to interrogate our own animal-ness. To that end, I’m often struck by the strangeness of living with a domesticated animal, but an animal nonetheless—how at times I can see Otto give into what we might call his “animal nature,” despite his training and domestication. A couple of months ago, Otto (somehow) grabbed a live bird out of the air in his teeth and only let go once I pried open his jaw. He’d just spent the morning sleeping beside my desk, docile, but right in front of me—and in a split second—he’d killed a bird. In moments like this one I’m reminded of my own human-animal modulations between desire, restraint, action.

Otto also makes his way into my poems because of our proximity—I see his face and body in each of the rooms of our apartment, in the park across the street, in the backseat of my car. I probably spend more time with him than any other living creature, so it makes sense that he appears in my poems, too.

“I wonder if some of our writing about animals comes partially from our desire to interrogate our own animal-ness.”

Your favorite poem about an animal or with an animal in it?

Paisley Rekdal’s “Why Some Girls Love Horses” and much of Robin Becker’s poetry, as animals (especially dogs) figure prominently throughout her work. She’s written two of my all-time favorite poems specifically about rescue dogs: “Rescue Parable” and “Rescue Riddle.” The lines “When she takes her morning tea, he settles / beside her – body of law and praise, / procuress, his winter and summer hearth” make me think of the routine I have earned with Otto.

Has caring for an animal helped shape how you see the world around you? If so, how?

Entirely, and that surprised me. My husband and I don’t have children, so we often hear from others that Otto is our child—a joke I’ve made a few times myself, too. Before we adopted Otto, I always rolled my eyes at people who referred to their dogs as their children, and I still find the comparison tenuous as I watch some of my friends become parents, but where I do see similarity (I imagine) is the way that keeping any sort of creature alive puts you on a spectrum of tested patience and earned love. I have agreed to care for Otto as long as he is mine; there is no opting-out or break-taking, because forgetting him would harm him. Even if he destroys something (his most recent chew-obsession, horribly, has been books!) or disobeys me, there is still no opting-out. There is more work to do to keep him behaved, perhaps, or longer walks that must be taken, but there is no backing away from the caretaking altogether.

I look at other dog owners in the park with an understanding that I didn’t possess before Otto’s adoption: what I’m understanding is what it feels like to have offered yourself up to an animal, knowing both the vastness of the work and the even more vastness of the reward, the love.

“What I’m understanding is what it feels like to have offered yourself up to an animal, knowing both the vastness of the work and the even more vastness of the reward, the love.”

Writing can put me in a weird headspace, but I've found that my dogs help pull me back to the surface afterward. Can you relate?

Absolutely, yes. Otto has become a reminder to me of how to access simple joys when my writing has cost me them, and a signal back to participation in the daily life I’ve “left” while writing—I have to walk the dog, have to feed the dog, have to hug the dog.

A simile for Otto?

Otto is like a tiny missile (but one that gives you kisses instead of blowing you up at the end?). He’s focused and incredibly fast and target-obsessed (very greyhound), and once he’s spent all his energy and reaches his destination, usually the couch, he’s warm and immediately inert.