Fox Frazier-Foley: What You're Given, What You Use

I was mindlessly scrolling Facebook the other day when I came across a video my friend posted about a man in Aleppo, Syria, who takes care of abandoned cats. Destruction and loss all around him, and here's this man, doing what he can to make the world a little kinder.

And that's one of the things Fox Frazier-Foley and I talk about today: the concrete ways she works to "make a dent in the terrible terrible awful," whether that's by rescuing her dogs or carving out space for writers to share their work. Bonus: she has some really good pointers for writers who are shopping manuscripts and for editors on inclusive publishing.

Before we get going, meet Fox: she's author of two prize-winning poetry collections, Exodus in X Minor (Sundress Publications, 2014) and The Hydromantic Histories (Bright Hill Press, 2015), and editor of anthologies Political Punch (Sundress Publications, 2016) and Among Margins (Ricochet Editions, 2016). Fox created TheThe Poetry Blog’s Infoxicated Corner, which she edits and curates. She is founding EIC of the small literary press Agape Editions.

Tell me a little about your dogs Dalí Nimbus and Oskar Wild.

Dalí was the first of the two to join our family; she's a Maltese & West Highland Terrier mix. It was love at first sight when I went to meet her. A larger, male dog came up and tried to menace her and assert his dominance over her, and she threw him on his back, then stood over him barking into his face. I thought it was so funny that she had such a tough-as-nails attitude (which would come to be less entertaining later—when she attempts to shout down the sky during midnight thunderstorms, for example, which is a self-assigned responsibility that she takes very seriously). Anyway, she literally jumped into my arms when I met her, and I knew that she was meant to be with me.

Oskar Wild is also a rescue dog—a Chihuahua mix, we think maybe a little corgi because he really likes to herd people. He'll nip at our ankles if one of us leaves the room when the family is chilling together at home to try to herd us back to the “pack.” We went through so much to get him! It actually took the help of several people, partly because he was bounced around a little bit before he made it to the shelter, and partly because the shelter lost him for a couple days after we had paid all the fees and finished all the paperwork! Their computer records showed that he had been taken to the vet, and the vet kept insisting that Oskar had never been brought to him.

So when we came to the shelter to find him, the staff told us we should just take another dog instead. I had spent several days bonding with him, and so I told them pretty emphatically that I didn’t think that that was a very good idea. We ended up searching the shelter, even though they were closed that day, and finally found him locked away in an empty part of the shelter that is only used for quarantine. No one could explain who locked him away or why. He had never even been taken to the shelter vet at all—which is something they won’t budge on: every dog has to be neutered or spayed by their vet specifically, so we had to wait a couple extra days, during which time I was a complete basket case and probably not the most pleasant person to be around. But at least the story has a happy ending! He’s curled up on my hip right now, making a complete baby face at me so I’ll stroke his (comically enormous and absolutely adorable) ears.

"It’s kind of like the Red Queen model of evolution..."

You know, I understand why shelters make folks jump through hoops to adopt animals—obviously, no one wants the animals to end up somewhere that’s not a good fit, but sometimes those hoops seem to box out really worthy owners. I’m glad that didn’t end up being the case with you and Oskar Wild!

So let’s segue to this question: why is it important to you to rescue dogs?

I know this is going to sound pretty dark, but I’m constantly aware, or almost constantly aware, of the fact that this world is a pretty terrible place. We talk about “progress,” and I guess that’s true—progress does happen—but in my mind, it’s kind of like the Red Queen model of evolution—many humans work so hard to be better and do better and make things better for as many people as they can—but the end result is that the human race is (at best) just barely able to keep some semblance of balance between what we might simplistically refer to as forces of good and evil. I suspect that the world has always been this way, and it will probably always be this way, until it ceases to exist.

And so, given that that is my worldview, I have a tendency to concentrate my efforts and energies in tangible or concrete ways that seem like they actually make a dent in the terrible terrible awful. So, obviously, rescue animals have usually had it pretty bad. I love animals and want to have them in my family, so to me, it makes sense to try to have that happen in a way that also helps reduce suffering. I know it’s a drop in the bucket, really, but that’s my general motivation.

Do your dogs affect how you think about or write about animals in your poetry?

They probably do, but probably not in a very overt way. I do think my dogs keep me very aware of the fact that we are all animals. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, either—I know we usually use it in a pejorative way, right, like a really heinous crime happens and we’ll say, “Only an animal could do that,” or “Even animals don’t do things like that,” but I think neither of those statements are really true. Again, I know this will probably sound dark, but from a practical standpoint that history has borne out pretty convincingly that humans do way worse things than animals—and that’s really saying something, because nature is pretty brutal.

But, overall, my dogs remind me that some animals—and this includes human animals—are extremely kind and gentle and wise, and some are very aggressive and predatory and cruel, and most are probably some combination of those two extremes. I know that we like to think we are not really animals, but we are. We are. And those ideas influence pretty much everything I write.

"I know that we like to think we are not really animals, but we are. We are. And those ideas influence pretty much everything I write."

I’d love to talk a little about your poem “St. Gemini Collages Photographs of Distorted Dolls in Vulnerable Poses Together With an Ancient List of Indigo-Colored Objects, and Glues Her Revelations Inside the Book of Truth and Water,” a poem you said “not only expresses how animals function in my work, but I think the poem itself is kind of animalistic.”

A lot of what it was trying to interrogate was the relationship within one human (animal) of predatory tendencies and fear or vulnerability (I guess qualities I would associate with feeling like “prey”). The reference to sirens / mermaids was intended to capture that as well. It's funny, because—this kind of goes along with what I was just saying about how I think people are animals—I also think that my dogs are very much like people. They have personalities. They can’t tell us everything that they understand, but they understand so much. (Look! Science agrees with me! Good job, science.)

To elaborate a little on one of my earlier answers, this poem is animalistic (and references those predator / prey qualities that I consider animalistic) because it reflects what I was saying about how my dogs can be wonderfully kind and sweet and loving, and yet they can also be terribly aggressive—sometimes in funny ways, like toward stuffed animals or Cheez-It crackers, and sometimes in less-funny ways, like toward each other (they’ve gotten into a couple knock-down, drag-out brawls over stuffed-animal toys, which I guess sounds a little funny after the fact, but when it’s happening it’s definitely NOT funny)! And so this poem was kind of a nexus for my considerations about ways in which we humans can love deeply and be enlightened and wonderfully kind, but at the end of the day, we also have incredibly violent tendencies coded into our DNA. (I don’t mean to say that I think everyone is physically violent, but I think we’ve all fallen into the trap of saying, “Oh, so-and-so couldn’t have done that awful thing—he’s such a nice guy!” But the truth, of course, is that sometimes even nice people do things that are aggressive or hurtful, things that they shouldn’t do.)

Maybe this stuff explains why my deep love for my dogs is often characterized by extreme silliness—because everything, all those really deep and terrible, visceral truths are always right there at the surface when I see them. It's a weird, refreshing kind of honesty—and the expressions of joy and tenderness they offer are really honest, too. You know, they literally celebrate when they wake up in the morning. They realize they're awake, and look at me and the tail waggles start, and then they start sneezing uncontrollably (this is how they express serious excitement—they sneeze uncontrollably, and it's the funniest thing ever), and then Dalí prances around digging excitedly on the bed and Oskar chases his tail in circles (he does this when I'm sad, too, because it cracks me up—I find it so endearing that he literally tries to make me laugh when I'm crying or sad). And then, like, they see a housefly moving through the air and their predator faces come out. Their lizard brains take over and they don’t want anything other than to catch and kill and eat that fly. I guess I’m glad I’m the mama and not the fly!

I was immersed in these kinds of thoughts when I was writing that poem. Those themes and concepts, and how they manifest in human tendencies, especially where power is concerned—physical power, access to resources, social hierarchies that govern our bodies—the poem, and the way it fits into the book it's from, was geared toward interrogating that human, animal balance.

"A good political poem would try not to reinforce (or innovate, for that matter) any traditions of systemic (or individualized) oppression."

I’m so grateful that in a poem about human power dynamics, you see the animal world there. I’m not going to get all vegan on you, but I think that intersection is such an important and often missing part of discourse surrounding existing power structures. But I digress. You recently edited an anthology of political poems called Political Punch, so let’s talk a little about the anatomy of a political poem. It’s been argued that everything is political, but I don’t really want to rehash that debate. Rather, I’m curious what you think a political poem should accomplish. And is anything off limits?

I think that probably a good political poem would try not to reinforce (or innovate, for that matter) any traditions of systemic (or individualized) oppression. I tend less toward saying any given subject matter should be off-limits, but more come down on the side of asking, “If you think you are the person to tell X story, why is that the case?” and then, “If you are the person to express X narrative or reveal X injustice or make X political statement, how can you do it successfully, and how will it evolve or otherwise depart from ways in which that’s already been done? What are you adding to the conversation? Why is your perspective on this important?”

So my tendency to ask those questions of myself and of other authors probably reveals at least what I react to when I read a political poem.

I think part of what makes me a good reader and a good editor is that I tend to approach a work on its own terms. And that might be why I really struggled to try to answer this question in a satisfactory way—I don’t know that I necessarily feel comfortable trying to prescribe what a political poem should accomplish. I tend to look for—and this is probably my best answer—essentially the same thing in a political poem that I tend to look for in any poem or piece of art, which is an experience that has been rendered for me by an artist.

For example, if you look at the Spotlight Series I’ve curated at THEThe Poetry Blog this year, you’ll see many poems that are political in nature (I admit, I am someone who finds nearly everything political in some way), but the aesthetics and approaches are strikingly different. Actually, for kind a very contained example of what I’m talking about, you could look at Cortney Lamar Charleston’s feature here: all three poems are political (at least, I think they are), but the approach(es) each poem takes are, to my mind, strikingly different. And that’s just from one author! Honestly, when we get too prescriptive or proscriptive, we lose—there are probably lots of ways to write a deeply compelling political poem. In a way, Political Punch is proof that I believe that because the work in it is so varied! It contains multitudes (ha).

"I think as an artist there really is nothing more valuable than finding your people."

I’d be remiss, given your editorial experience, not to ask you for some advice for poets when it comes to finding the right press for their books. And you have insight from both sides of that—you send out your own books and publish the work of others. So, let’s hear it: your best tips for getting a manuscript in front of the right audience.

For me, nurturing friendships with other artists who are truly good people has probably been the most important thing. I’ve definitely been burned a few times (of course, not everyone who seems like a wonderful person is actually going to be a wonderful person or a supportive friend—sometimes you learn the hard way), but I’ve also managed to find people who really are community to me— they understand and value my work, they support me, they want to see me succeed. I think as an artist there really is nothing more valuable than finding your people. There’s a sort of weird psychic alchemy that happens as those friendships begin to flourish: you share your art, you have conversations, you help each other grow as artists, as people.

Those influences help you dust yourself off after something demoralizing happens, help you own and celebrate your successes. In that way, they build your confidence and your resilience. And those types of friends are the people who can give valuable, trustworthy opinions on where you might send your work, when you’ve got a manuscript seeking a home. For me, this is what has meant the most.

I suppose I’ll spare a word here, too, toward not getting too discouraged when you see people with tons of privilege take advantage of nepotism and seem to sail carelessly—really, without care, much less actual effort—into easy successes while you have nothing and are still working as hard as you can. That can be really rough on a person. It can make you feel like you have nothing going for you. I want everyone who has been made to feel this way to guard themselves, to the best of their abilities (please!), against falling into that slimy psychic spiral. I want to say to them: do your best to utterly ignore those people and their entitlement. They aren’t your concern. They really aren’t. You and your work are your concern.

“These are the tools you were given, not the only tools you can use.”

From your experience as a poet, writer, editor, and publisher, what is one piece of advice you’d offer other gatekeepers when considering work for publication?

As an editor, I have this weird little made-up phrase that I repeat to myself sometimes, which is, “These are the tools you were given, not the only tools you can use.”

What I mean is that a few different influences train us in how we read and what we look for. Right? Little subconscious qualifiers about what’s “good” and what isn’t (well, maybe some conscious ones, too, but those are easier to apprehend because we’re aware of them). I’m not saying that there shouldn’t be standards—I don’t think all writing is equally artful or that everyone’s writing or art is always just as good as everyone else’s—but we need to be really mindful of what shapes and informs those standard for each of us. Racial privilege, gender privilege, body privilege—and, to be honest, I think one that’s very overlooked in the indie-lit industry: class privilege—shapes us as readers.

I once worked at a literary publication where a few staff had sort of peripherally considered the idea of publishing something by someone whose literary career had not included a course of graduate study. I thought it was a worthy objective, for sure. But then we got several submissions from authors who didn’t have academic backgrounds, and most of these authors, from their bios, clearly had very different socioeconomic and social-class backgrounds from the people who were reading and evaluating their work.

A lot of what I heard in staff conversations about those submissions revealed to me that, while everyone liked the idea of non-academic writing, a lot of people struggled with the reality of non-academic writing. They wanted writing and aesthetics that were familiar to them, that reflected the qualities they had been taught to value. They essentially wanted an MFA story or poem written by someone who didn’t have an MFA degree. But someone who doesn’t have that type of educational background isn’t necessarily going to have all those same values or the same approach! I remember feeling sort of defeated by those conversations, despite the fact that we didn’t really have many exchanges on the subject. I did point out that if we were looking for writing from a different perspective than what we were used to, then we should probably be open to writing that was different from what we were used to. I was met with radio silence.

But one positive thing about that experience was that it really did crystallize for me how editors—and also people who aren’t editors—can have good intentions and want to be inclusive, but can maybe fall into the trap of thinking that the tools they’ve been trained to use in evaluating writing—or evaluating other things out in the world—are the only tools they can use to that end. They might be useful tools, but they aren’t the only tools.

What are you working on right now? And what are you reading?

Two of the projects I’m working on right now are a novel about the social gentrification of tattoo art and a few other types of labor, and a book of poetry that’s kind of a supernatural take on the American cultural mythologies of hitch-hiking.

What I’m reading right now: The Art of Work by Jen Fitzgerald; Prophet Fever by Wren Hanks; Violet Energy Ingots by Hoa Nguyen; and all the books and e-books that Agape will be putting out in 2017 (they’re really good!).

"The poet Mark Irwin once said to me that the reason we keep pets is because they're the last vestige of the Garden of Eden."

I’m circling back to something you said a few questions ago—you mentioned silliness is a prominent part of your relationship with your pups, and I think that’s a cornerstone of Dog Magic. One of my favorite things to do is (very) dramatically read poem drafts out loud to my dogs. That playfulness makes it easier for me to write the really difficult stuff so I don’t get too lost in it. Has that playfulness crossed over into your work, process or otherwise?

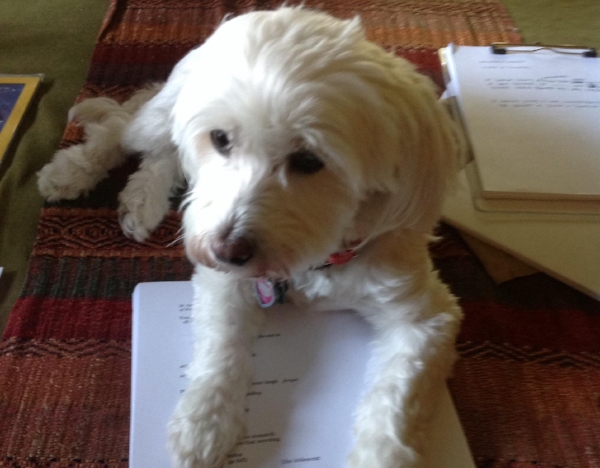

I love that! My dogs really hate it when I work on anything. To illustrate how ornery it makes them, I’m including a photograph of Dalí Nimbus from a few years ago, when she had climbed onto my desk and laid herself down on top of the final draft of my about-to-be-published book to protest the fact that I was not giving her enough attention (read: I was petting her with one hand and making notes with the other. Impermeable puffball of self-interest says, Not good enough, Mom!). Oskar, on the other hand, climbs up onto my lap or my shoulder and hits me in the face repeatedly until he gets my attention.

Anyway, all of this is by way of saying the way they help me through the more difficult moments of my work is that they pull me out of the muck afterwards, very quickly, and they take up as much psychic space as they possibly can, so they divert my attention from things that might otherwise send me into a psychic spiral. They remind me of good things in the world. They remind me of love.

A simile for your dogs?

The poet Mark Irwin once said to me that the reason we keep pets is because they're the last vestige of the Garden of Eden—I love that. So, for my simile about my dogs, I decided to riff off that a little bit:

As Charon & Mercury ensconced

in downy hide, they guide me

to the Garden where man spurned

his holiest self: huddled & howling what

gleaming marrow down in our exile.