David Winter: A West-Facing Window in Coal Country

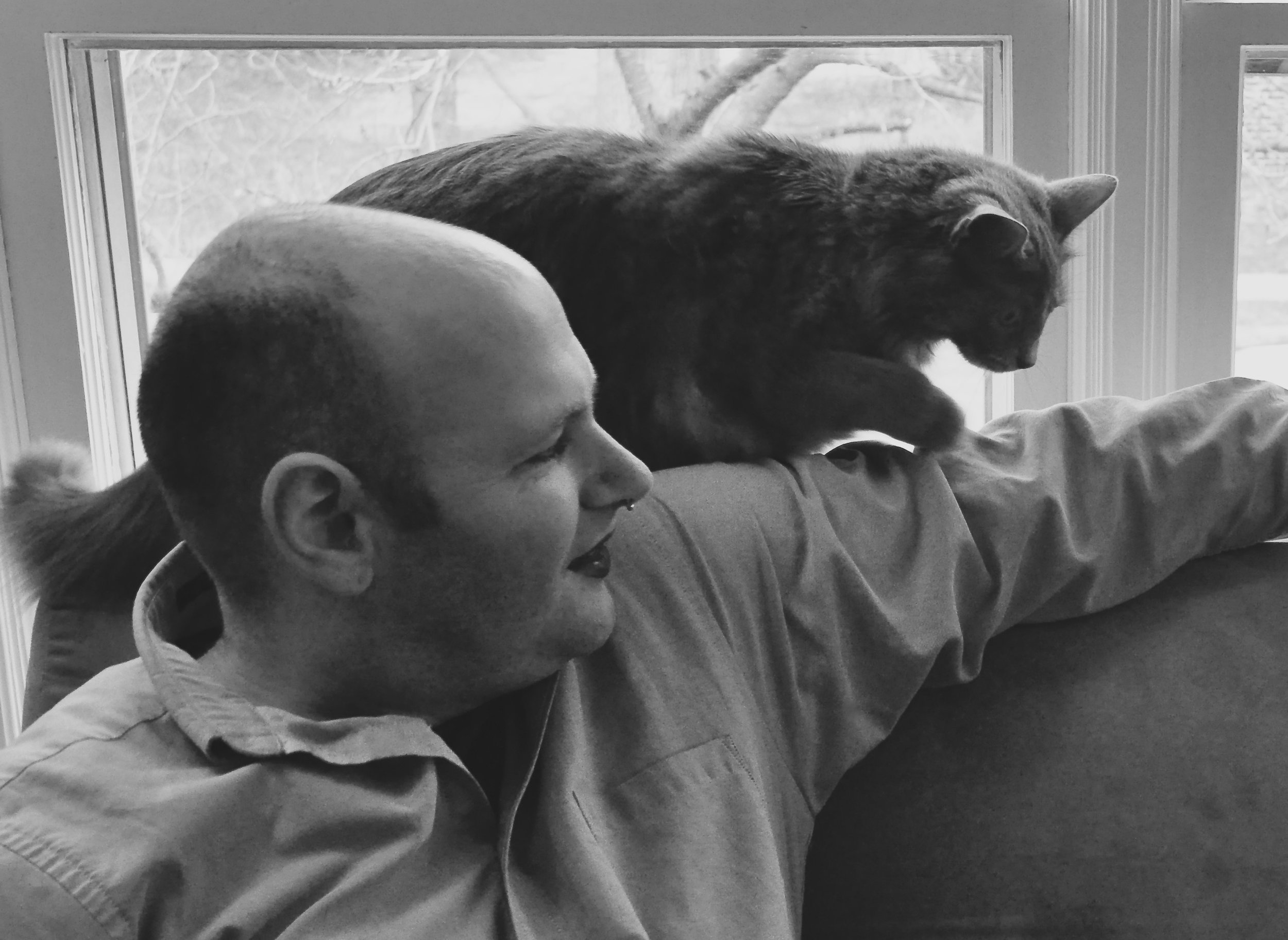

Photo by the exuberant Raena Shirali

I know you're here for pets and poetics, but let me just say: no one rocks deep-plum lipstick like David Winter. And that's not even scratching the surface of this surprising, talented, considerate person and poet. You'll see.

Here we talk about his lovely cat Emily Cream McWinterson III, his hopes for what exists in the space between his lines, the best line of poetry he's ever written, the art of listening, what makes or keeps people safe, and more.

A bit about David: he is a 2016-18 Stadler Fellow at Bucknell University, the recipient of a 2016 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, and author of the poetry chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013). His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Baffler, The Dead Animal Handbook, Forklift, Ohio, Meridian, Muzzle, New Poetry From the Midwest, Ninth Letter, Winter Tangerine, and other publications. His interviews and reviews have been published by The Journal and the Poetry Foundation. You can find more of his work here. And more pictures of Emily here.

Tell us a little about your cat Emily Cream McWinterson III. I’m guessing she’s as regal as her name suggests?

Like most cats, Emily Cream McWinterson III occasionally strikes a regal pose, but like most members of long and illustrious lines (including imaginary ones), she’s also rather fussy. I don’t mind her fussing most of the time, but her insistence on talking about every step she takes and every craving she experiences does undercut the more dignified visual impression you get in photos. But if you’re the kind of person who likes talking to cats, Emily’s actually a very personable animal, and I think she really tries to be a good friend. There’s this idea about cats being indifferent to humans, but when I’m home and she’s awake, Emily rarely leaves my side. She’s very affectionate and also conscientious of boundaries, at least to the extent that a cat can be. I pretty quickly trained her not to wake me up too early in the morning. And after watching me scoop her litter into plastic bags a few times, she started trying to help by pulling the plastic bags into the litter box after she used it and burying the bags along with her droppings. Of course that actually made more of a mess, but I appreciated the gesture.

How has having Emily’s companionship shaped your writing life? It seems like she may be more than just a bystander to your work.

Emily has been a really important source of emotional support in my writing life. I adopted her shortly after moving to a small town in central Pennsylvania for a fellowship at the Stadler Center for Poetry. The fellowship itself and becoming a part of the the creative community that the Stadler Center cultivates has been an enormous gift and privilege—one I wouldn’t trade for anything. But as a queer Jewish poet who had lived my whole life in or around cities, when I suddenly found myself in the middle of coal country during the 2016 election season, I felt pretty anxious and isolated. I’m a fairly anxious person to begin with—I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and social anxiety disorder as a kid, although I’m ambivalent about what those diagnoses mean—and I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done.

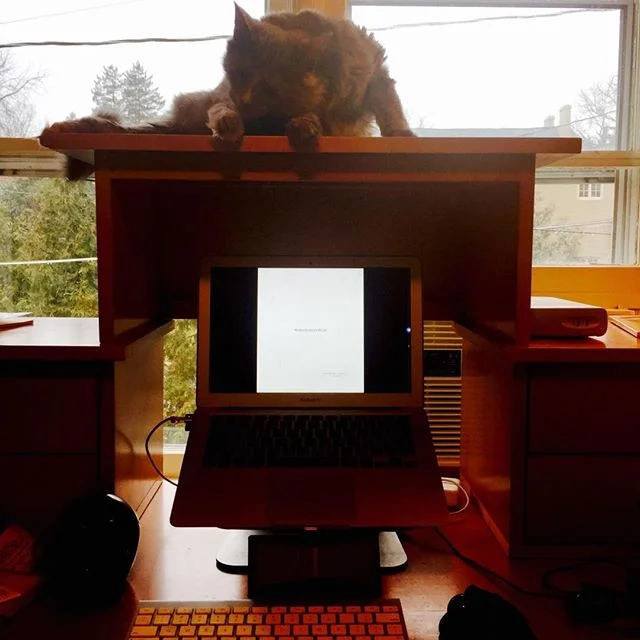

After I adopted Emily, I positioned my desk in front of a west-facing window, and the desk has a built-in shelf above the computer that gets some sunlight in the morning. I usually write for a couple of hours in the morning while Emily lies on that shelf, soaking up some sun and watching the birds, or just napping. It’s really an ideal arrangement because I can enjoy her company while I write, and she’s usually comfortable and occupied enough that she doesn’t walk all over the keyboard while I’m working. I’ve learned that when I feel too anxious to write, I’m better off taking a few minutes to play fetch with her and then returning to work more calmly, rather than opening up Twitter and panic-scrolling through the endless stream of news about the death-throes of American democracy.

"I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done."

I recently read your chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013), and I’m really compelled by its guiding question: “What makes a place safe?” Some poems seem to answer with the psychological (“Introductions” and “Lament With Cello Accompaniment”). Others explore or subvert safety as a physical space (“Parole”). And perhaps my favorite is how we find safety in others (“To Ask Our Bodies” and “Luciano Serafino’s Lover” – especially the line “Men like us / only ever find salvation in the dark.”). Can you talk about how you arrived at this theme?

Thank you for reading the work so closely. In some sense I’ve been thinking about this almost as long as I can remember, and I’m not certain why that is, exactly. I remember as early as second or third grade feeling very cynical about the social boundaries that were supposed to protect kids emotionally—the idea that if someone picked on you, you could tell them to stop or get an adult to protect you, for instance. That idea just seemed absurd to me, although I don’t think I was getting picked on or picking on anyone else all that much. But when I did get picked on, instead of confidently drawing a boundary, I often let things go until I got mad enough to hit back. Maybe this all has to do with being a queer kid before I knew I was queer, or maybe it has to do with my anxiety disorder, or maybe it’s something else altogether. I don’t know.

As I’ve gotten older, it has only become more clear that there’s no reliable adult stepping in to save us from ourselves or each other, and so we have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can. I grew up in what a lot of people would consider a safe and sheltered suburban town, and while I certainly benefited from the privilege that geography afforded me, there are also poems in this chapbook about watching one of my closest childhood friends smoke crack, and how my perception of the world changed the first time he came home from jail and told me what happened to him there. It was really during those years of late adolescence when I started to understand how the safety of the environment I grew up in was predicated upon barely concealed violence.

"We have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can."

In this chapbook, the poems are lithe and really put that whitespace to work. Henri Cole once told me (I’m paraphrasing here) that what goes unsaid in a poem can be as powerful as what we write. We were talking about Franz Wright, but I see this at work in your poems, too. Can you talk about the art of deciding what exists in the spaces between your lines?

That’s a great question. I think one of the hardest parts of learning to write poetry for me was (and is) accepting that I don’t entirely get to decide what happens in that space between the lines. Because it’s not just the space between the lines themselves, which would be a two dimensional space I could shape, and which might remain fixed and static once I’d shaped it. The space between lines is always also the space between the lines and a reader, which makes it a three-dimensional space somewhat beyond my control as a writer. And so I guess I’ve learned to make my peace with that reality by becoming almost obsessively controlling and deliberate with the language I do put on the page, in the hope that a reader will really engage with my work as they inhabit the imaginative space it creates. But I do think what happens there is ultimately up to the reader.

Here's a hard question: what’s the best line of poetry you’ve ever written and why?

I have no idea at all how to answer this question. Maybe because of what your last question was getting at—for me so much of what happens in poetry happens outside the lines, between the reader and the lines—or maybe just because I lack the distance from my own work to judge. But perhaps one answer is that the line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line. At any given moment the line-in-progress has the most potential energy; it has the potential to become something we’ve only begun to imagine.

"The line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line."

True or false: A poem can teach a reader how to listen.

True, so long as someone is speaking the poem. I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music. But I do think the poem must be read aloud; otherwise what we’re talking about is looking, and that is a different (although equally worthwhile) conversation. From what I understand most people subvocalize as they read—meaning they make imperceptibly minute movements and sounds—particularly when they’re reading something emotionally engaging or intellectually challenging, which poems tend to be. So I guess what I’m really saying is, yes, a poem can teach a reader how to listen, but the onus is on the reader to engage actively in that project.

What’s your favorite poem ever written about a cat? And do you write about Emily, either directly or indirectly?

I am working on a poem about Emily. It’s about two-thirds of the way finished and I can’t seem to figure out the ending, although I visit the text every week or so and try to figure out where it’s heading, what it wants. At first I thought it was about how much I loved her and also how fascism is encroaching upon and threatening everything we love, but I showed it to a poet I really admire when she visited the Stadler Center and she disagreed. She said it really just seemed to be a poem about a cat, or perhaps about a cat and how we hurt the ones we love. So I’ve been going back and forth on that for a while, exploring these different trails, but not quite finding my way. Who knows where it will end up, or if it will really end up going anywhere at all.

As for the other part of your question, T. S. Eliot’s “The Naming of Cats,” the opening poem in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, is by far my favorite cat poem. There are points in that book—as in pretty much all of Eliot that I’ve read—where his perpetual xenophobia and other prejudices not-so-subtly show, but the musicality of the language is top-notch, and it’s far more fun than most of his other books, and that poem in particular has a very strange wisdom to it. If he wasn’t so obviously a jerk, I’d give a copy of that book to every parent of young children I know, but alas, whiteness strikes again . . .

"I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music."

A metaphor or simile for Emily?

Well, she didn’t turn out to be much like her namesake, Emily Dickinson. I suppose in some ways she’s more like Whitman. Her mouth never closes for long, but I’m thankful for that, because she contains multitudes.