Brandon Jordan Brown: Satan Must Love Animals

Poet Brandon Jordan Brown on his cats Wyatt and Little Bear, writing about spirituality, the absolutes that exist for him in poetry, and the one statement about poetry he can stand behind for five (or 50) years.

I'm going to keep this introduction short and sweet because I am so excited for you all to check out this interview with Brandon Jordan Brown, a poet whose craft is outshined only by his generosity – and maybe his cute kitties. Friends, I even stole the title for this interview from a line of one of his poems because I love it too much. I had the singular honor of chatting with Brandon for a few hours about everything – growing up in the South, how animals help define a place in his poems, religion, schools of poetic thought, and some advice any writer would be wise to remember.

DID I MENTION HE HAS A KITTEN RIGHT NOW? Let's do this.

Some background: Brandon was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in the South. He is a PEN Center USA Emerging Voices Fellow, winner of the 2016 Orison Anthology Poetry Prize, a scholarship recipient from The Sun, and a former PEN in the Community poetry instructor. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Grist; Scalawag; Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review; Forklift, Ohio; Day One; Winter Tangerine Review and elsewhere. He currently lives in Los Angeles and you can follow his work here.

Note: The following interview has been edited for both length and clarity. Enjoy!

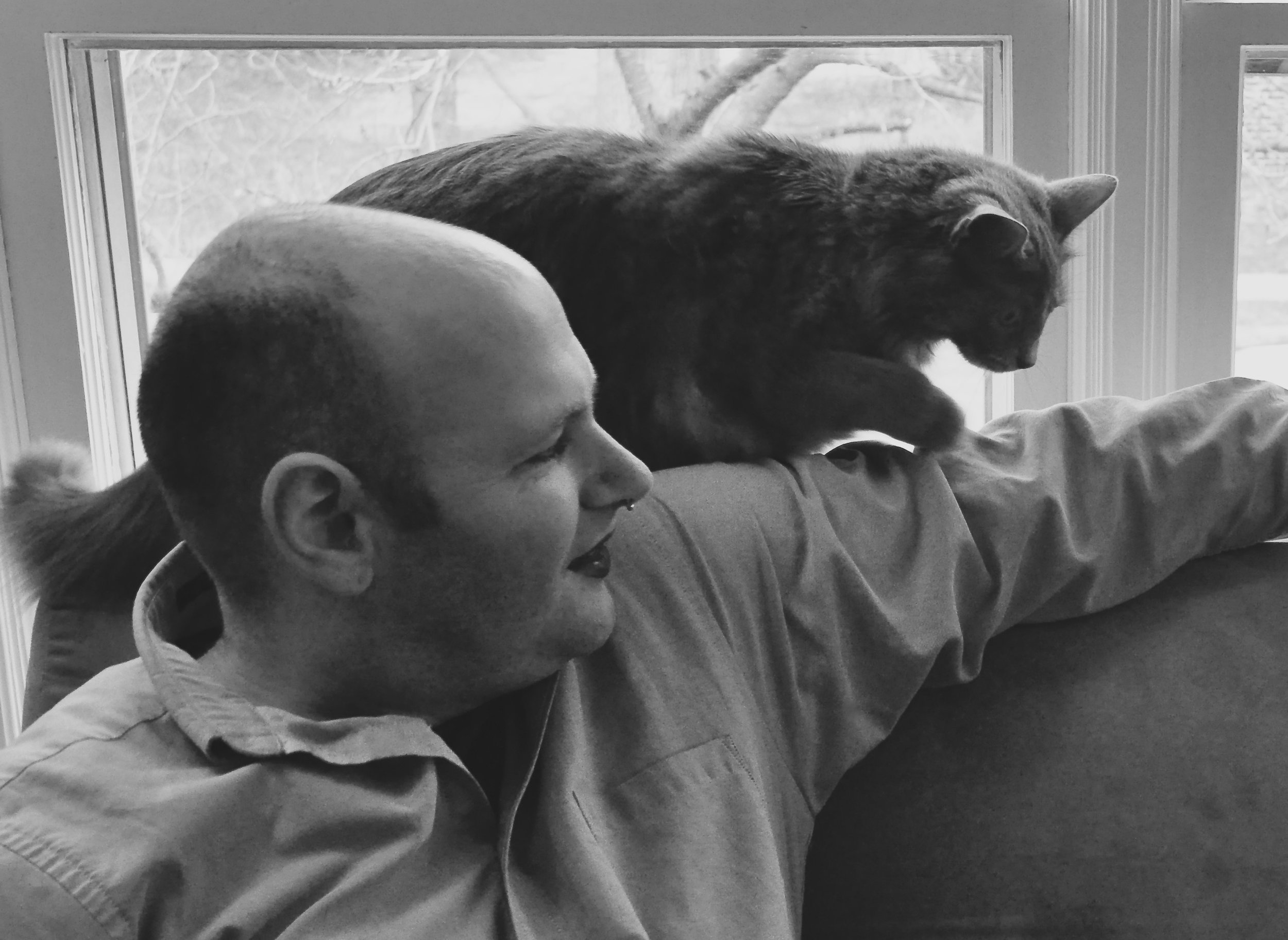

Photo: Little Bear, a tortoise-shell baby cat, sitting on stack of books on a desk.

I guess this is a good time to ask about your cats. So tell me everything – how your cats came into your life, how they changed things for you – everything.

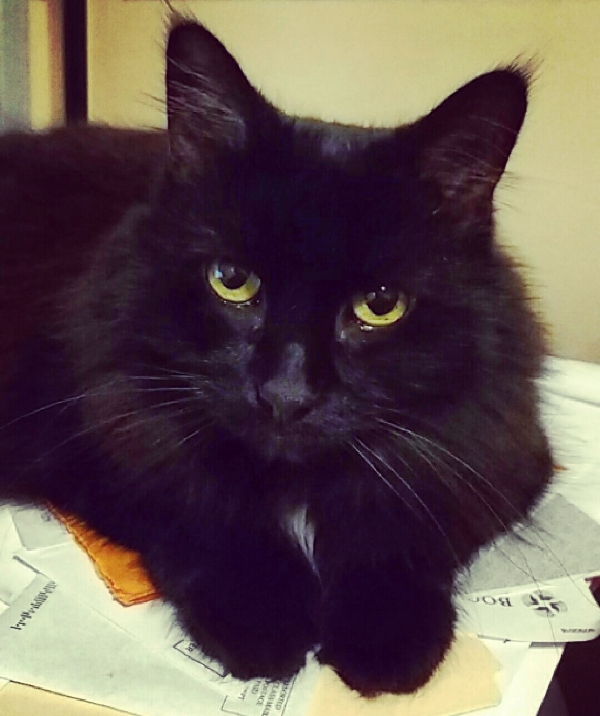

We have two cats. The older brother, his name is Wyatt. He's a tuxedo cat, and we adopted him from a shelter out here a little over a year ago when he was a few months old, and he is such a unique cat. He is a very needy cat. He is very high maintenance, but he's such a sweetheart. He wants engagement and play, but that can be tricky when you're not always able to offer it because you have to go to dinner after work or you make plans to go on a date or go hang out with friends.

And we made the decision to adopt another cat so he can have a friend. So we were at the vet getting Wyatt a checkup because of his behavioral issues and told the doctor we thought about getting another cat. And they said, “We have some kittens in the back that you should come check out.” And that's where we found Little Bear. She’s brand new to our family. We've had her for a little under a month now and she's tiny, tiny, tiny, a little tortoise-shell cat. And she's been so good for Wyatt. Wyatt has a friend, we have more love in the house. Last night, I was sitting in a chair in my living room with her asleep on my lap and him asleep on my chest. And I had achieved a rare moment of joy. Like I was I was fully in a moment.

And we only have plans to get more animals. We would really love at least one dog. Having a goat would be rad. I have big dreams. Give me a cow. Give me everything. I want it all.

My favorite piece of cow trivia is they have best friends.

That's amazing. And I think, too, the idea of having animals is almost synonymous with a certain pace of life. Like having pets and being able to tend to your pets is a sign that you have enough space in your life to care for something and to develop a relationship with something. I think that is one of the most powerful things about what it means to have animals – this ability to take time to be slow. Especially living in the city, that can be very hard. And coming from where I grew up [in Alabama and Tennessee], it's almost like it has a heavy symbolic weight, that idea.

"I think that is one of the most powerful things about what it means to have animals – this ability to take time to be slow."

That falls in line with something that I always tell people about what changed in me when I got animals, and it's that caring for animals takes you out of yourself, you know? It gets you off your bullshit.

There's something unique about that: pulling you out of yourself to care for something. I mean I even see it in [my] relationship [with my wife]. It's like only one of us bottoms out at a time because as soon as one of us does, the other person snaps to attention to care for that person. I think we do the same thing with pets, too.

Pets are magic. So let me ask you: have your pets ever influenced or inspired your poetry? Specifically, I want to ask you about your cats inspiring some of the lines in your poem "Satan," which is amazing:

The sun has a particular way of cutting

through the blinds and lighting up

the cat’s spine. That sunlight is all Satan.

And so I must make peace with two hells cooking me

at once: the hell below me and the one above

this ball of light and its army of swirling moons. Now I hate birds.

And this wonderful line: “Satan must love animals, too.”

For some reason, it's kind of rare that I write about things that are happening in the present for me. I almost have this feeling the things that need to be in my poems need to have some sort of sticking power so that I'll be proud of them sticking around later, I guess.

But animals from my childhood make an appearance in my poetry. I have poems with my Papaw's goats or the cow in the backyard that he got angry at and he punched. And because a cow is much stronger than my Papaw, it broke his hand. Just standing there, being a cow… So I have animals that pop in and out of my work all the time. But I'm in a season of writing right now where I'm focused a lot on recalling memories from the past and sorting through all that. So maybe I'll have some really good poems about Wyatt and Little Bear in like 2020, 2022. Look for them; they're coming.

Photo: Wyatt, a tuxedo cat, looking up at the camera with soulful eyes.

You know, some people sit down and write every single day. Maybe that lends itself more to poems born of the present. I write whenever I feel like it, and I usually reach far back into my most painful past.

So are we in the glutton for punishment school? When people talk about literary movements, is that where our names are going to pop up?

You know, I hope that my name pops up under that school because I would be very proud.

Because our last names are close, we may be near each other in the list. We may be just a few commas away.

That would be a really great anthology. So hold on that idea and then take my work.

It's really just you and me dialoguing back and forth about being super sad.

Being sad and loving animals.

That's it. A great working title.

My follow-up question: I was reading every poem of yours I can find online. And in your poems "Boyhood" and "Biology," I notice that you use animals to help tell a story about a place's values and also about masculinity and its expectations. For example, in the poem "Boyhood," you write:

This is how things are to be done. How a man is to be made: by pushing

logs that fall from the backs of trucks into the ditch across the road and

whipping the mutt that follows you to the mailbox each day

until it feels thankful and a little scared to even be alive.

So I was hoping you would talk about the relationship between animals and place – how you use animals in poems to help shape a place and its mood and its values.

Animals, they're so intimately connected to a place. How they share space with you. I grew up with animals everywhere. Like lightning bugs – those don't exist in other parts of the country, but I know what they are. And I remember having memories directly connected to an animal that doesn't exist other places. And my home in Tennessee – we always had dogs and right beside us was a field full of cows. And then you'd go visit your grandparents and there are more animals down there, animals to be afraid of and animals to get excited to see. For the sake of writing, they almost can become a literary device in a way to pull out the feeling.

I think there is something about our relationships to animals that closely mirrors our relationships to each other. So a defenseless, even confused or clueless dog getting beat – that's only a small subset of things that we do to each other. And that's both in the tenderness that we show and in the violence that we commit against each other. You look through history, and one way that we oppress whole groups of people is to liken them to creatures that are not human. On the other hand, we call people we love pet names, right?

"You look through history, and one way that we oppress whole groups of people is to liken them to creatures that are not human. On the other hand, we call people we love pet names."

Exactly! So I read that you are working on your first book of poetry. Do you want to talk a little bit about that project, the scope?

I have a chapbook manuscript that is done – several of the poems that you've mentioned are in there. And the big thrust of it is really some of the themes that you nailed down just by reading a couple of pieces that you found online. It deals a lot with growing up in the South. That is my whole lineage, I guess, that's the place that shaped me in a lot of ways. Maybe even in the most unconscious of ways, the most subtle and unexamined of ways.

And I didn't even realize until I was ordering the manuscript how big the theme of manhood or masculinity was until I started looking at it as a whole, cohesive unit and having other people give me feedback on it. I had this idea that it was about faith, a lot about the landscape, a lot about family, relationships.

One of the themes is based off of Saint Augustine's understanding of sin, this idea that your love is out of order, the things that you are pouring your love into are disordered. And so you need to reorder them to flourish or live the best life. You have to pour your love into the right places. So the book is a wrestling with what it means to love someone or something. How do I do that, and in what order? That's how we end up spending our life, I think – trying to figure out how to do that.

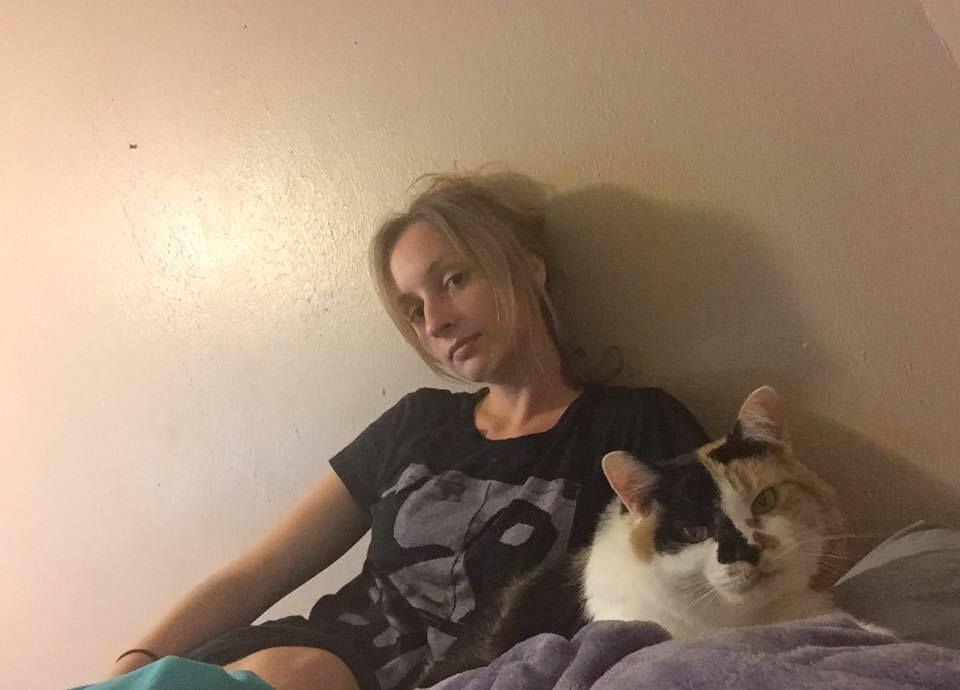

Photo: Brandon with Little Bear, faces together.

I never thought about that before and I really like that concept. I kind of hate to think about how much of my time and effort I pour into like my job, my work. So in your own life, where do you think you're placing your love and do where you want to place it?

Oh my gosh. That question is terrifying. I guess one of the questions that I have a lot is: how much love do I place on myself? Because that can be a very tricky question to answer. And I think maybe there's a thing in me, there's an impulse in me, that says leaning too far in either direction is wrong. Like overly loving yourself at other people's expense or self indulgence or super ego-driven narcissism – I never want to lean in that direction, but I also want to be kind to myself. I had a mentor one time tell me that I needed to talk to my own heart like I would a friend because we can be so hard on ourselves. And I want to be able to do that.

That is such a difficult balance to strike. Can I ask a prying question? Do you consider yourself a religious person?

I do. So I got into religious studies, thinking that I would maybe take a more traditional, vocationally religious life trajectory. And as I moved further and further in that direction, it started to feel less like a full expression of who I am. That is a part of me. And even if that's the central part of me where everything else flows from, in many scenarios, there's only one way that you can show that side of yourself. And I feel like through the arts, I'm able to do it as a much fuller expression of who I am.

Are there special considerations you make when writing about your faith? I'm angling at how you approach writing and engaging with your spirituality on the page.

I mean, to put it bluntly, all I think about is God. That's I think a really succinct statement that requires a ton of unpacking. That's my chief source of questions. If you're taking faith seriously, it necessitates so many questions – like how could we imagine that we can easily encapsulate the infinite?

"Poetry is a long game... I don't have to say it all at once."

You could write about that for a lifetime and never be done. Ok, here’s a hard one: make a statement about poetry you think you could stand by for the next five years.

What a rad question. I think for the next five years, you could confidently walk up to me at any moment and I would always say, I should be writing more. That is definitely a statement I will probably be able to say in the next 50 years.

You could put that on any poet’s gravestone.

"Should've wrote more. Could have been a contender." I guess some advice I give myself all the time – and this is maybe less about the effect of poetry and more about the practice of writing poetry – is that you don't have to say it all at once. That poetry is a long game. And I think that makes me feel better when I start getting anxious about my output or my momentum or my personal satisfaction with how often I'm writing or investing in the community. I think that's advice that is always good for me remember: I don't have to say it all at once. When you're a poet, you don't retire from being a poet. And that gives me a lot of comfort.

Is there any particular subject that you absolute won't write about? Do absolutes even exist for you in poetry?

I don't want to co-op someone's story or use someone else's pain for some strange artistic benefit because we see that a lot in the history of writing. We still see it happen today, and there are a lot of really good conversations happening around that idea. And I don't want to be a person who does that. When that happens, something about the work has gotten off track, whether the writer realizes it or not. I don't want to make that mistake, so I think about it a lot. Like, I've started this project where I'm working on a series of persona poems, so I've been asking myself, why do I want to do this project?

Photo: Wyatt on Brandon's shoulder.

I feel like poetry and memoir have always kind of dovetailed, but maybe even more so these days, you see a lot of memoir's influence in poetry. And I know for memoir, that's a huge question: what stories do I have a right to tell, what stories are mine?

I feel like throughout our whole conversation, everything feels like to me it's this question of interrelatedness and neighborliness. A lot of our conversation today has been defining our relationships to things or other people that orbit in our sphere. I guess to bring it full circle, in the New Testament, there's this question that gets posed: "Who is your neighbor?" It's kind of a rhetorical question. The whole point of the story is to basically point to the fact that everyone is your neighbor. And we're supposed to treat our neighbors with dignity and love and respect, and I feel like that's kind of one of the central themes that keeps popping into my mind in this conversation – this question of like neighborliness to animals or people. And it's really interesting.

You tend to look outward with your answers, which is really refreshing. I really appreciate when people have that worldview of looking beyond themselves consistently.

I hope so. Long may it continue! Thank you. I guess I should just say thanks.

"Everyone is your neighbor. And we're supposed to treat our neighbors with dignity and love and respect."

So I watched the videos for a couple of your poems on your website. I was wondering if you had a background in visual art? And what’s the process for pairing poetry with visual imagery?

So before I found my way into writing, I was a musician in high school, in college. I started learning the bass guitar in eighth grade, and in high school, I joined my first hardcore band and I was the screamer in this hardcore band. When you’re in a band, it matters that you have T-shirts. It matters that you put on a good performance as opposed to just writing good music. And I think because I have that background, I'm just very interested in how things look. And so I think a video can be a really cool way to bring some of those elements in and to connect with people who are maybe even too intimidated to read the poem on the page because they don't know how to approach it. And so video could be a really cool way to kind of bridge that gap and jump over that threshold.

The guy who I shot those videos with is a buddy of mine, Dru Korab – he's an amazing filmmaker – and we have plans to make more because if it's really about making an impact, getting your work into the world, and making some sort of contribution, then I think collaborating with other artists who have that same impulse in a different medium can be a really cool way to do that.

I’m going to talk about Beyoncé for a second. My favorite parts of Lemonade are when she reads Warsan Shire's poetry. The images paired with the spoken word is some of the most striking stuff I've seen in a long time. I really love how visual imagery can elevate the imagery in the words of the poem.

Yeah, totally. Maybe some people are nervous because they're afraid that it will supersede the poem. But that is the artistic process of figuring out how to say it best. We cut and add new words and phrases all the time to our poems. I think if you're even approaching the visual component like that, it can be similar. It doesn't have to overcome the poem. It can be a nice complement.

It also makes poetry accessible for people who depend on listening to experience poetry, too.

That's a super great point for sure.

Photo: Close-up of Little Bear, her paws stretched out in front of her, looking unbearably cute.

Are you ready for your final question?

Let's do it.

I need a metaphor or a simile for Wyatt and Little Bear.

I'm going to say that Wyatt by himself is a single tooth in a mouth because I think all of the proper elements are there. But our experience with him is he cannot do his best alone, he cannot be his best alone. So he needs another tooth. You're not chewing any food with one tooth.

Little Bear feels like a bubble that won’t burst. Where the whimsy and the exploration and magic is there, but I also don't have to fear that it will burst suddenly.

It's just so, so cheesy, right?

David Winter: A West-Facing Window in Coal Country

Poet David Winter on his lovely cat Emily Cream McWinterson III, his hopes for what exists in the space between his lines, the best line of poetry he's ever written, the art of listening, what makes or keeps people safe, and more.

Photo by the exuberant Raena Shirali

I know you're here for pets and poetics, but let me just say: no one rocks deep-plum lipstick like David Winter. And that's not even scratching the surface of this surprising, talented, considerate person and poet. You'll see.

Here we talk about his lovely cat Emily Cream McWinterson III, his hopes for what exists in the space between his lines, the best line of poetry he's ever written, the art of listening, what makes or keeps people safe, and more.

A bit about David: he is a 2016-18 Stadler Fellow at Bucknell University, the recipient of a 2016 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, and author of the poetry chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013). His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Baffler, The Dead Animal Handbook, Forklift, Ohio, Meridian, Muzzle, New Poetry From the Midwest, Ninth Letter, Winter Tangerine, and other publications. His interviews and reviews have been published by The Journal and the Poetry Foundation. You can find more of his work here. And more pictures of Emily here.

Tell us a little about your cat Emily Cream McWinterson III. I’m guessing she’s as regal as her name suggests?

Like most cats, Emily Cream McWinterson III occasionally strikes a regal pose, but like most members of long and illustrious lines (including imaginary ones), she’s also rather fussy. I don’t mind her fussing most of the time, but her insistence on talking about every step she takes and every craving she experiences does undercut the more dignified visual impression you get in photos. But if you’re the kind of person who likes talking to cats, Emily’s actually a very personable animal, and I think she really tries to be a good friend. There’s this idea about cats being indifferent to humans, but when I’m home and she’s awake, Emily rarely leaves my side. She’s very affectionate and also conscientious of boundaries, at least to the extent that a cat can be. I pretty quickly trained her not to wake me up too early in the morning. And after watching me scoop her litter into plastic bags a few times, she started trying to help by pulling the plastic bags into the litter box after she used it and burying the bags along with her droppings. Of course that actually made more of a mess, but I appreciated the gesture.

How has having Emily’s companionship shaped your writing life? It seems like she may be more than just a bystander to your work.

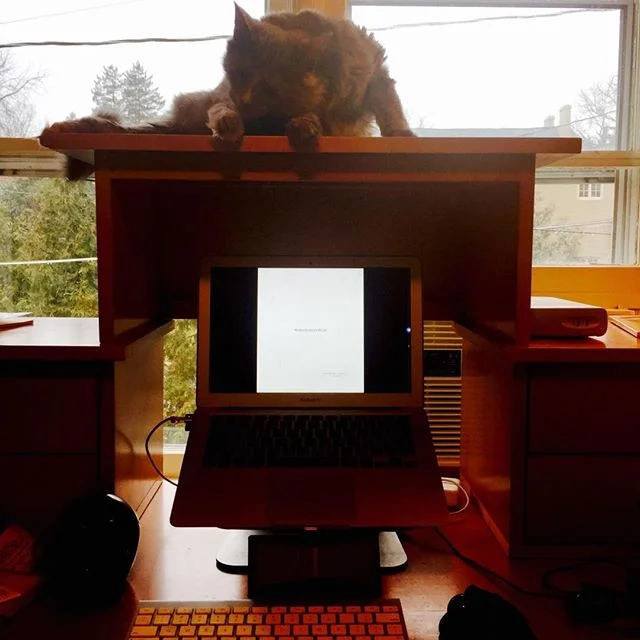

Emily has been a really important source of emotional support in my writing life. I adopted her shortly after moving to a small town in central Pennsylvania for a fellowship at the Stadler Center for Poetry. The fellowship itself and becoming a part of the the creative community that the Stadler Center cultivates has been an enormous gift and privilege—one I wouldn’t trade for anything. But as a queer Jewish poet who had lived my whole life in or around cities, when I suddenly found myself in the middle of coal country during the 2016 election season, I felt pretty anxious and isolated. I’m a fairly anxious person to begin with—I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and social anxiety disorder as a kid, although I’m ambivalent about what those diagnoses mean—and I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done.

After I adopted Emily, I positioned my desk in front of a west-facing window, and the desk has a built-in shelf above the computer that gets some sunlight in the morning. I usually write for a couple of hours in the morning while Emily lies on that shelf, soaking up some sun and watching the birds, or just napping. It’s really an ideal arrangement because I can enjoy her company while I write, and she’s usually comfortable and occupied enough that she doesn’t walk all over the keyboard while I’m working. I’ve learned that when I feel too anxious to write, I’m better off taking a few minutes to play fetch with her and then returning to work more calmly, rather than opening up Twitter and panic-scrolling through the endless stream of news about the death-throes of American democracy.

"I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done."

I recently read your chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013), and I’m really compelled by its guiding question: “What makes a place safe?” Some poems seem to answer with the psychological (“Introductions” and “Lament With Cello Accompaniment”). Others explore or subvert safety as a physical space (“Parole”). And perhaps my favorite is how we find safety in others (“To Ask Our Bodies” and “Luciano Serafino’s Lover” – especially the line “Men like us / only ever find salvation in the dark.”). Can you talk about how you arrived at this theme?

Thank you for reading the work so closely. In some sense I’ve been thinking about this almost as long as I can remember, and I’m not certain why that is, exactly. I remember as early as second or third grade feeling very cynical about the social boundaries that were supposed to protect kids emotionally—the idea that if someone picked on you, you could tell them to stop or get an adult to protect you, for instance. That idea just seemed absurd to me, although I don’t think I was getting picked on or picking on anyone else all that much. But when I did get picked on, instead of confidently drawing a boundary, I often let things go until I got mad enough to hit back. Maybe this all has to do with being a queer kid before I knew I was queer, or maybe it has to do with my anxiety disorder, or maybe it’s something else altogether. I don’t know.

As I’ve gotten older, it has only become more clear that there’s no reliable adult stepping in to save us from ourselves or each other, and so we have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can. I grew up in what a lot of people would consider a safe and sheltered suburban town, and while I certainly benefited from the privilege that geography afforded me, there are also poems in this chapbook about watching one of my closest childhood friends smoke crack, and how my perception of the world changed the first time he came home from jail and told me what happened to him there. It was really during those years of late adolescence when I started to understand how the safety of the environment I grew up in was predicated upon barely concealed violence.

"We have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can."

In this chapbook, the poems are lithe and really put that whitespace to work. Henri Cole once told me (I’m paraphrasing here) that what goes unsaid in a poem can be as powerful as what we write. We were talking about Franz Wright, but I see this at work in your poems, too. Can you talk about the art of deciding what exists in the spaces between your lines?

That’s a great question. I think one of the hardest parts of learning to write poetry for me was (and is) accepting that I don’t entirely get to decide what happens in that space between the lines. Because it’s not just the space between the lines themselves, which would be a two dimensional space I could shape, and which might remain fixed and static once I’d shaped it. The space between lines is always also the space between the lines and a reader, which makes it a three-dimensional space somewhat beyond my control as a writer. And so I guess I’ve learned to make my peace with that reality by becoming almost obsessively controlling and deliberate with the language I do put on the page, in the hope that a reader will really engage with my work as they inhabit the imaginative space it creates. But I do think what happens there is ultimately up to the reader.

Here's a hard question: what’s the best line of poetry you’ve ever written and why?

I have no idea at all how to answer this question. Maybe because of what your last question was getting at—for me so much of what happens in poetry happens outside the lines, between the reader and the lines—or maybe just because I lack the distance from my own work to judge. But perhaps one answer is that the line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line. At any given moment the line-in-progress has the most potential energy; it has the potential to become something we’ve only begun to imagine.

"The line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line."

True or false: A poem can teach a reader how to listen.

True, so long as someone is speaking the poem. I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music. But I do think the poem must be read aloud; otherwise what we’re talking about is looking, and that is a different (although equally worthwhile) conversation. From what I understand most people subvocalize as they read—meaning they make imperceptibly minute movements and sounds—particularly when they’re reading something emotionally engaging or intellectually challenging, which poems tend to be. So I guess what I’m really saying is, yes, a poem can teach a reader how to listen, but the onus is on the reader to engage actively in that project.

What’s your favorite poem ever written about a cat? And do you write about Emily, either directly or indirectly?

I am working on a poem about Emily. It’s about two-thirds of the way finished and I can’t seem to figure out the ending, although I visit the text every week or so and try to figure out where it’s heading, what it wants. At first I thought it was about how much I loved her and also how fascism is encroaching upon and threatening everything we love, but I showed it to a poet I really admire when she visited the Stadler Center and she disagreed. She said it really just seemed to be a poem about a cat, or perhaps about a cat and how we hurt the ones we love. So I’ve been going back and forth on that for a while, exploring these different trails, but not quite finding my way. Who knows where it will end up, or if it will really end up going anywhere at all.

As for the other part of your question, T. S. Eliot’s “The Naming of Cats,” the opening poem in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, is by far my favorite cat poem. There are points in that book—as in pretty much all of Eliot that I’ve read—where his perpetual xenophobia and other prejudices not-so-subtly show, but the musicality of the language is top-notch, and it’s far more fun than most of his other books, and that poem in particular has a very strange wisdom to it. If he wasn’t so obviously a jerk, I’d give a copy of that book to every parent of young children I know, but alas, whiteness strikes again . . .

"I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music."

A metaphor or simile for Emily?

Well, she didn’t turn out to be much like her namesake, Emily Dickinson. I suppose in some ways she’s more like Whitman. Her mouth never closes for long, but I’m thankful for that, because she contains multitudes.

Rochelle Hurt: Between Place and Identity

Poet Rochelle Hurt on her cat Frida, her newest poetry collection, and the relationship between place and identity.

I debated whether or not to pick up this series again. It seemed an insurmountable task after losing Pete, my beloved dog who inspired this project. But it feels like the right way to honor her. She was, after all, my favorite writing companion.

This is a long way of saying: welcome back, lovers.

Rochelle Hurt is up today, and we discuss her cat Frida and her latest book, which explores how place shapes people. It's a timely topic given what's going on right now (re: our country using nationalist appeals to keep folks out).

A little about Rochelle before we get to it: she's the author of two poetry collections: In Which I Play the Runaway (Barrow Street, 2016), which won the Barrow Street Book Prize, and The Rusted City (White Pine, 2014). She is the recipient of awards and fellowships from Crab Orchard Review, Arts & Letters, Hunger Mountain, Poetry International, the Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fund, Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. You can find recent poems online at The Awl, American Literary Review, and Phoebe.

Tell us a little about your cat Frida. How long have you had her? What’s her origin story?

Frida has a great origin story. Twelve years ago, a college boyfriend and I went looking for a mythical cat warehouse we’d heard was full of strays who needed homes. Alas, it did not seem to exist, but near its rumored location we found a veterinary clinic, so we stopped in to ask if they knew about this warehouse. The vet staff we encountered at the front desk had not heard of it, but as we were about to give up and go, another vet approached the desk and said: “Do you want a cat? I have a cat for you! She’s right here!” She led us into a closed exam room, and there was Frida wandering around on the floor. She greeted us immediately. The vet said that Frida (unnamed and six months old at the time) had arrived in her backyard with no collar or chip and starting meowing loudly until she was let in—but the vet couldn’t keep her, so she’d been bringing Frida to work during the day. I have no idea what the first six months of Frida’s life were like, but when we got her home, we discovered that she already knew how to play fetch.

What’s the most poignant way your pets have impacted your life?

I’ve been lucky in that I haven’t—in all my thirty-two years—lost a very close friend or family member yet. It’s sort of incredible, actually. I have lost a pet though—Trotsky, feline companion to Frida and me. He was only five, so his death was unexpected, and it was the first time I’d ever felt such grief. His absence was enormous. He’d been a big showoff, and was very friendly to strangers—jumping in their cars when he was outside, head-butting their palms for attention. He was the most enthusiastic cat I’d ever known. Most poignant I think was the way in which he remained so alive and real to me after that. I’d always thought of pets as family members, but until then I hadn’t considered how resonant their spirits could be—or how expansive their lives. The day after we buried Trotsky, I got cards and condolence notes from several neighbors in my building (a big house divided into apartments) whom I’d never met. They all wrote about how they knew Trotsky—he’d visit them and play while they were in the backyard, the driveway, etc. It turned out he had more friends in the neighborhood than I did.

After that it was just Frida and I living together, and I think we became much closer, more emotionally reliant on one another. She’s been with me now longer than any other companion I’ve had in my adult life. That’s a serious bond.

"I’d always thought of pets as family members, but until then I hadn’t considered how resonant their spirits could be—or how expansive their lives."

Have you written a poem about Frida yet, and if so, what spurred it? If not, do you think you will one day?

I tried to a few times in college—not by name, but using her image. I don’t think the poems were very good. They were all breakup poems, and she and Trotsky were always lazy symbols of something like loneliness. I never tried to actually write about them in any specific way. I’ve noticed that I rarely use animals in my writing, and I’m not sure why that is. Maybe one day I’ll commit to more animal writing and give Frida a narrating role. She’d be good at that; she’s very direct.

I read your newest book over the holidays – In Which I Play the Runaway (Barrow Street Press, 2016) – and loved, loved it. I especially admire how this collection recasts small towns in middle America as their own sort of Oz. It’s like these poems are a collective voice of these towns: Needmore, Indiana; Honesty, Ohio; Hurt, Virginia. I also love how the Self-Portrait poems use place as a mirror for the speaker. Can you talk a little more broadly about how place came to be a lynchpin for this book?

Place has always been fraught for me because I grew up in a place that gets a lot of flak: Ohio—more specifically, the Ohio Rust Belt. When you tell people you’re from Youngstown and they say, “That’s a rough area,” or (jokingly) “I’m sorry,” you can’t help but internalize the idea that you are also, as a product of that place, somehow inferior. We tend to conflate place and character—as a show of camaraderie and as a form of insult. From one angle, it’s comforting; from another it’s diminishing—especially since culture and class are so often woven into our perceptions of place.

When I moved from Ohio to North Carolina, I began thinking about this relationship between place and identity. I was homesick, but also dealing with a breakup, a new relationship, and a jumble of fears about domestic life that were rooted both in lived experience and in fictions I’d created about who I was. The personal traits attached to place are not inherent, though it can sometimes feel as if they are. For me, this paralleled the ways in which I’d let some of my family history and personal habits become an excuse for fatalism and self-destruction. With the self-portrait poems I replaced the usual “self-portrait as” conceit with a “self-portrait in” conceit to suggest how profoundly origin and setting can inform identity and warp self-image.

"We tend to conflate place and character—as a show of camaraderie and as a form of insult. From one angle, it’s comforting; from another it’s diminishing—especially since culture and class are so often woven into our perceptions of place."

From a craft perspective, what changed the most between your first and second books? Was either harder to write? If so, why?

Both books are, incidentally, about place—but formally they are fairly different from one another. My first book, The Rusted City, is a narrative collection comprised mostly of linked prose poems. That writing came easy. Once I was creatively invested in the world I’d begun to build, sitting down to write felt almost like lucid dreaming. All my characters would be there waiting for me when I re-entered the space of the book.

In Which I Play the Runaway is more of standard collection in that it’s largely made up of discrete poems. That said, there is an arc of sorts, and several recurring series braided into the book. Writing this one was harder because I didn’t know it was a book at first. I was writing all these different series with shared themes, but I didn’t try to put any of it together until I already had a quite a lot to work with. Then I had to continue writing new poems and shaping the collection as a whole. Because of the nature of my first book, I’d never organized a collection primarily by theme, motif, tone, or anything other than narrative. So this time around, I learned that there are countless ways to organize a collection. After rearranging and revising until I could barely stand the poems anymore, I realized that I just had to choose a structure and stand by it.

“Inheritance” might be my favorite poem of this collection – those closing lines:

Don’t even open the door to your old room—the world

in there won’t know you.

This is how a house ends: once emptied,

the walls erode as the wind picks up,

and you are left

coaxing your memory back like a dog.

For this reader, it names the specific loneliness of leaving and returning to one’s home. But it’s the image of the dog, I think, that breaks my heart. There’s something about calling for an animal that makes you know desperation, whether it’s for their trust or just to bring them safely to you. Do you find you often turn to animals when the human world needs edification in your poems?

You found an animal poem! There are only a few in there—notably, dogs (including Dorothy’s Toto). I think in this collection I turned specifically to dogs because people expect them, unlike cats, to come home when called. That’s a lot of pressure.

I think I sometimes turn to animals when considering vulnerability and loneliness. I remember reading a passage by Derrida in “The Animal That Therefore I Am” about language as a wall between humans and other animals. Our relationships with them are fraught because we want so badly to convey to them that we understand their experiences, but we can’t—not fully. They remind us of our own animality, but this is somewhat frustrating because we can’t fully connect with them on a linguistic level. As someone who is deeply invested in verbal and written language, this holds some truth for me. I think we do want animals to teach us things about ourselves—and sometimes they do, but sometimes they just don't. I can project this feeling of separation onto Frida the cat and assume that she wishes she could better communicate with me, too—but perhaps she doesn’t. We’re both animals existing in this house together, but our realities could be entirely different in ways that neither one of us will ever know. That doesn’t detract from my love for her—and it may not affect her love for me—but it’s still a lonely realization.

"We’re both animals existing in this house together, but our realities could be entirely different in ways that neither one of us will ever know."

What’s bringing you to the page these days and what’s next for you (readings, new projects)?

I’m working on a third collection of poems that is more of a world-building project akin to my first book. It’s about this group of adolescent girls and all the ways in which language and consumer culture shapes them into performers of femininity, for better and worse. For example, one series in the book riffs on pickup lines and aphorisms. Another draws narratives from the names of beauty products. I’ve got a lot of poems at this point, but I just started toying with the idea of adding an annotation element, so I’m excited about it. Also, I’m about to finish my PhD this year!

A metaphor or simile for Frida?

Since you got me thinking about that Derrida passage, now I’m also thinking about Lia Purpura’s essay “Sugar Eggs: A Reverie.” In it, she describes the sensation of peering into spaces that are physically inaccessible—or accessible only through imagination, which requires a splitting of self. She writes: “The space is a privacy into which, as a child, I imagined, not my body but myself, eye to the window at the egg’s pointed end, the dim, egg-shaped world before me.” A cat’s mind isn’t exactly the same thing, but I’d like to borrow Purpura’s sugar egg as a metaphor for my human-feline relationship with Frida. Her feline point-of-view is only accessible to me through an imaginative process that places me outside of my human body. We’re so close, but she remains in some ways a mystery. Given their nature, that’s probably just how cats want it.

Sandy Longhorn: Stranger Muses

Poet Sandy Longhorn on how her cats inadvertently helped her write her latest book, why caring for animals is soul-growing work, and how to be a good literary citizen.

I'm grateful for this chat with Sandy Longhorn for so many reasons. She's incredibly insightful and generous with said insight (if you get the chance, interview her at once). But so much of what she said about caring for her ill cats really resonated with me. Caring for sick animals is almost always sure to invite unwanted opinions about "quality of life," so it's a relief to hear from someone else who finds it a worthy endeavor, despite the high emotional cost.

This week, we talk about how Sandy's cats inadvertently helped her write her latest book, why caring for animals is soul-growing work, and how to be a good literary citizen.

But first, meet Sandy: she's the 2016 Porter Fund Literary Prize winner and the author of The Alchemy of My Mortal Form, winner of the 2014 Louise Bogan Award from Trio House Press, The Girlhood Book of Prairie Myths, winner of the 2013 Jacar Press Full-Length Poetry Book Contest and Blood Almanac, winner of the 2005 Anhinga Prize for Poetry. New poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Cincinnati Review, diode, Hayden's Ferry Review, Hotel Amerika, The Southeast Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere.

Sandy holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in poetry from the University of Arkansas and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from the College of St. Benedict. She teaches for the Arkansas Writers MFA Program at the University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR, where she directs the C.D. Wright Women Writers Conference. In addition, she blogs at Myself the only Kangaroo among the Beauty, accompanied by her cat George.

When we first started chatting about this interview, you wrote, “My spouse and I have loved and lost three cats in our 10 years of marriage, with George still with us, who we adopted with Gracie, after the loss of Libby and Lou-Lou, each to unpreventable (and in one case bizarrely rare) diseases.”

Has losing so many companions in such a short amount of time affected how you think about or interact with your last living cat George?

With Libby and Lou-Lou, their deaths happened within months of each other, and we spent those months after Libby’s death in and out of the vet’s office trying to keep Lou-Lou alive. We were in crisis mode the entire time. Things are different now.

George is an older cat who suffers from hypothyroidism and kidney disease, but in the wake of Gracie’s death, we are only in maintenance mode and living a fairly normal life. Still, that fear hovers over us all the time. From George’s point of view, now that he is an “only” cat, he is loving all of the attention.

A few months ago, you lost your cat Gracie, and I know that was exceptionally hard for you. Has writing played a role in coping with the loss?

Writing does play a role in my coping with loss; however, not in the most direct way. Aside from a blog post, a few emails, or a Facebook update, I haven’t written directly about any of the cats or their deaths. However, that mourning pops up in my poems in other ways and adds a layer of gravitas to the work.

True or false: poetry is a form of coping.

Truth. Poetry helps me cope when writing it, sure, because I’m working through issues and emotions even when I’m not writing directly about a loss. However, for me, the real coping happens by reading the poetry of others. I was drawn to poetry first as a reader because a poem has the power to make such a quick connection with the audience and to leave memorable lines as touchstones.

"The real coping happens by reading the poetry of others."

Lou-Lou

You mentioned your third book The Alchemy of My Mortal Form (what a great title, by the way) was in part inspired by your cat Lou-Lou's rare blood marrow disease. Can you elaborate?

Thanks for the compliment on the title. This book is a collection of poems all in the voice of a single persona, a woman suffering from a difficult to diagnose illness. Her situation is complicated by the fact that she is hospitalized and completely alone. She has no visitors and only communicates with one other person through letters that may or may not ever get mailed.

I wrote the first poems right after Lou-Lou’s diagnosis and wrote much of the collection just after her death. Lou-Lou was diagnosed with “a fever of unknown origin.” When antibiotics didn’t clear it up, blood tests revealed shredded red blood cells. Working with a specialist, we eventually received a diagnosis of myelofibrosis: an immune-mediated disease causing her immune system to attack her bone marrow and make it fibrous as layers of scar tissue built up. She put up a good fight with steroids and immune system-suppressant drugs, but she died about four months after we learned the source of the fevers.

What’s odd is that the book revolves around a human being, and there isn’t a single cat in it. The drafts occurred organically, and it never crossed my mind to write about my own feelings of caring for and then losing Lou-Lou. As the poems in the book unfolded, two things were happening. One was Lou-Lou’s medical treatment by our awesome team of vets; the other was my father’s medical treatment by a host of doctors and nurses for both Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s. Fortunately, my father is still with us.

"Writing the book gave me some sense of control over a situation that is always out of our control in real life."

As we worked with our vets, Chuck and I were constantly awed by their willingness to go above and beyond for our cats. Often, one of the vets would call us at 7:30 p.m. (closing time is 6:00 p.m.), still at the office, still researching treatments or just providing some feedback and comfort. These people were proactive in giving our cats the best quality of life while also fighting for that life, and when the time came to make hard decisions, our vets were compassionate and honest.

On the other hand, even today, while a few stand out as exceptional, most of my father’s doctors might not remember his name, often have schedules so full that he gets only a few minutes with them at each visit, and my mother has to raise hell to be an advocate on his behalf. It was an amazing juxtaposition, and the book turned into an indictment of what I call the “medical-industrial complex,” as the sickly speaker has to navigate her treatment, in this case, all alone without any advocacy.

The last thing I’ll say is that while Lou-Lou’s death was a fact by the time I wrote the second half of the book, I myself didn’t know if the speaker was going to live or die until I wrote the last poems. Looking back, I can see that writing the book gave me some sense of control over a situation that is always out of our control in real life.

I love that you said part of being a caregiver is “embracing empathy and sadness at the same time.” If you don’t embrace the empathy and sadness, you’re swimming upstream, right? You’d have to deal with these overwhelming feelings all while trying to take care of someone you love.

While I admit that sinking too far into the sadness of a loved one (animal or human) with a terminal diagnosis can be harmful, I believe we lean too far in the opposite direction. We are conditioned, especially in the US, to deny sadness and whitewash our mourning. For me, allowing myself to be sad throughout all three cats’ last days helped me survive their deaths.

I do believe that Libby, Lou-Lou, and Gracie have all taught me important empathetic lessons about being a caregiver and mourning a loved one. I don’t think this means I’ll weather another loss any easier, but I’ll be less confused, more caring, and more willing to give myself a break when I need one.

"We are conditioned, especially in the US, to deny sadness and whitewash our mourning."

Libby

Are there specific poems you turn to when you seek out comfort?

Mary Oliver’s “In Blackwater Woods”

Lucille Clifton’s “won’t you celebrate with me”

Stephen Dobyn’s “How to Like It”

Emily Dickinson’s “After great pain, a formal feeling comes”

Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art”

Let’s switch gears a little. In your blog post “The Work Behind the Reward,” you write, “I've made a conscious effort to champion writers I admire, whether I know them or not. I've made a conscious effort to read widely and diversely to combat the gatekeepers. When I read a poem that blows me away, I Tweet/Facebook post about it. Often, I send private messages to a poet when I've read something that strikes me as extraordinary. Most importantly, I buy books of poetry, so many books of poetry that I don't have time to read them all.”

To me, these are the hallmarks of good literary citizenship, something I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. What other advice do you have for poets who want to support the community and make it more inclusive?

Seek out writers of work different from your own and interact with them and their work. We are living in a time of amazing access to all manner of voices. Take advantage of all that the online world has to offer (but don’t get sucked down the time-waste drain – some self-control is required).

Writing is hard, and many writers are more inclined to introversion, so going out and seeking literary events and other writers can be tough from the beginning. Once we find our crowd, I think we are in danger of inertia. This is not to discount the support of a solid literary community, but one runs the risk of stagnating and writing the same poem over and over again. Along with this, I think the poetry world, in particular, is prone to cliques and those cliques can lead to a kind of us-versus-them mentality. Before we can change this tendency, we have to be aware of it in ourselves.

All art is subjective, and I’m not saying we have to force ourselves to enjoy art that isn’t to our taste; however, if we don’t read widely, how will we know what our tastes are?

"If we don’t read widely, how will we know what our tastes are?"

Gracie

On your blog, you often write about the process of drafting your poems. Does blogging about the process help you revise the poems or write poems in general? Also, please tell us the secret to diligent blogging.

Hah! Your last statement makes me laugh. Once upon a time, I was quite diligent. In fact, you can find draft notes on the blog for all of the poems in The Alchemy of My Mortal Form and many of the poems in my second book. However, I’ve fallen out of that practice. In part, this is because I recently started a tenure-track job with more responsibilities than I had in my previous position at a community college. Like all things, blogging well takes time and concentration, two things I’ve been short on lately.

That being said, posting draft notes was once a great motivator to keep my BIC (Butt in Chair) and to keep me writing new poems. I confess that just a few comments on a blog post is enough gratification to make me want to post the next set of notes, propelling me to write the next new draft.

What projects are you working on now? I noticed a few blog posts about a “self ekphrasis” project based on your collages… tell me more!

When I’m not working on poems, I often work in collage. Last year, I starting thinking about a project where I would make a certain number of collages and then write poems in conversation with them. Once the project became a reality, I called this “self ekphrasis” since I was working with my own art, and the collages always came first.

One of my goals with this project was to try and explore my subconscious in a new way to find out if I had other obsessions lurking there. I tried my best to let the images of the collages guide the process. With the collages in hand, I sat down to draft the poems. After several false starts and a few weeks of frustration, everything clicked and I was able to draft a matching poem for each collage.

The result is “20 x 20: a Self-Ekphrastic Poetry Project,” which includes 20 collages and the 20 self-ekphrastic poems. I’ll spend the next few month revising the poems and sending out poem/collage pairs for publication. The ultimate goal is to publish a collection of the complete project.

Working my way back to George – do you think he’ll show up in a poem one of these days? And a follow-up: when are animals mostly likely to appear in your poems?

This is a great question. None of the cats have ever been mentioned in a poem, I don’t think. So, there’s a good chance this will remain true for George as well. Although, maybe this will be a new draft challenge. I admit that I might have steered away from poems about Chuck and the cats, or from even including them tangentially, because of the way these subjects often result in women’s poetry being labeled “domestic” as a way of lessening its importance.

I’m also fascinated with the next question. The animals most likely to show up in my poems are non-pets: coyotes, fox, bobcat, birds of all kinds, wolves, bears – they’ve all been there. I’ll be thinking about why this might be the case and what I’m trying to say by featuring the wild over the tamed.

"These subjects often result in women’s poetry being labeled 'domestic' as a way of lessening its importance."

Lou-Lou & Libby

A simile or metaphor for your cats?

George has a voice like a firehouse alarm when he is hungry or lonely, but he is my mindfulness guide, reminding me to stay in the moment.

Gracie was a green-eyed bowling ball of a diva; she was the only cat that never lost weight on chemotherapy.

Lou-Lou was Tony Hawk’s shadow; she could leap and zoom with the best of them.

Libby was my blood pressure medicine, hot water bottle, and bed burrower.

Jess Feldman: Carry the Wild

Jess Feldman talks about how her cat Willicus helped buoy her through a difficult year and offers writers who work that 9-to-5 hustle some pointers on finding and maintaining creative space for poetry.

Fact: today you'll learn why Jess Feldman doesn't care much for llamas (spoiler alert: they have a v. annoying superpower), the connective thread between Frank O'Hara and her cat Willicus, and her sage advice for melding the 9-to-5 world with the creative life.

Teasers aside, what a joy it is to talk to a poet who is so mindful in the way she moves through her environment. Perhaps that's why she is both a poet and a quilter – both arts require the endurance to advance stitch by stitch.

Before we get to it, a little background: Jess Feldman is a writer, editor, and third-generation quilter originally from New England and now based in New York City. Her manuscript Call It a Premonition was chosen by poet Zachary Schomburg as winner of BOAAT’s 2015 Winter Chapbook Prize, and her poetry has appeared in numerous publications, such as Sixth Finch, Transom, The Portland Review, Vinyl and Tuesday; An Art Project. She holds an MFA in writing and a BA in English from the University of New Hampshire, and currently works as the office manager at a boutique entertainment law firm in Brooklyn.

Let’s hear a little background on your cat Willicus. What a name!

First off, the name breakdown: Matilda > Tilly > Tilly-Will > the Willicus. Purrfect sense, right?

I've had my cat for nearly seven years now (she'll be seven in September – a Virgo / Libra cusp). My partner Mike Luz & I have been together for nearly nine years, and I can't believe that for those first years we didn't have our cat Tilly "the Willicus." How did we survive?!

Willicus is a mere eight pounds, loves salmon & destroying things slightly, and despises cylinders (specifically my round hair-dryer brush). I always saw myself as a dog- & horse-person, but isn't it wonderful to continue to live & find out how truly big and ever-expanding the heart can be? There are so many cool, amazing creatures out there to inspire love & compassion in humankind.

But to be honest, there is one furry creature I don't particularly like and that's llamas. The llamas I've met don't really acknowledge your presence. Instead they emit a high-pitched noise while slowly backing away – I believe that if you were to sustain that llama noise in a direct hit, your entire being would be eliminated off the face of the planet. However, I did see something about a therapy llama named Rojo who may be able to change my mind. Like I said, my heart could hold love for a llama someday.

Back to my cat…

I picked up the Willicus on a chilly, dark night in November 2009. She was one of two kittens left and was raised by a woman who lived in the New Hampshire woods. Willicus's dad was a feral cat of the woods, which is why she's still kind of half-feral (or as Mike & I say: half-domesticated). I told myself the first kitten to walk over to me would be my cat, and that's the Willicus for you – she's bold even when she's scared or uncertain. When I was driving her back to my apartment, she somehow wriggled her way free of the soft cat-carrier I had in my car and made her way onto the seat next to me. #copilot4life

2009 was a difficult year for me. This scrap of a tabby cat sauntering into my life with her sassy strength & take-no-holds approach to enjoying life buoyed me. She continues to be a source of inspiration to me when I feel besieged by the world and its demands. Her talents for napping and playing with junk (elastic bands, tissue paper, plastic bags) help me find balance in the here & now when so often I get tied up in my mental & emotional maelstrom. Willicus is the antidote to world-weariness.

"Willicus is the antidote to world-weariness."

That’s been true for me, too – animals seem to sustain my emotional endurance. Sometimes I’ll look up from my work in full existential-crisis mode and think, I can’t do this for another minute, and then Pete or Bear will look at me with their funny little faces and their sweet eyes, and I’m like, okay, do it so you can buy dog food. That pragmatic motivation that comes with caretaking can be so essential for the minute-to-minute existence, right?

Definitely. It’s a relief to get out of my head in those moments, and it’s a gift to be beholden to something that’s perpetually adorable.

You write for a living now, correct? My experience says that word work (at times) can be mentally exhausting in uncharted ways! What’s your experience been like? And how do you compartmentalize / reserve creative energy for your poetry work?

I do more editing and curating of material now, but no matter what, I use my work experiences as opportunities to gain new language (structure, concepts, diction) that I can fold into my own work. In essence, poet-brain is on all the time for me. Poet David Rivard got me into the habit of tagging good words, ideas, etc. into a small Moleskine. It helps me keep the chaos anchored somewhere and feel productive even if I haven’t had a moment to pull together a complete poem.

Living the 9 - 5 office life at times can feel like I’ll never get any good writing done. Instead of seated somewhere picturesque and quiet with pen & paper, I’m answering phones and emails. In those moments, I remind myself that poems don’t just live in vacationland. Poems live in that mundane free-for-all of our inner & outer lives. They may not look like much at first, but brush them off and they shine.

"I remind myself that poems don’t just live in vacationland. Poems live in that mundane free-for-all of our inner & outer lives."

On to poems! My nerd heart is so happy that you write a lot about animals. Let’s talk about one poem in particular – “Hinterland” – a poem you described as your “calling-all-animals / New-Hampshire-girl manifesto.” For our readers, a few lines:

Crowded with light, am I so grave that what were once maned wolves are now purple

asters?

Are ladles as stiff, as accurate as a flock of hooded merganser?

I have never been a person in the world with hands held out, anticipating Communion.

I have not been that honest.

You, bright helix: Touch; tell this touch I am far from things I knew.

How important are animals in telling the story of a place? In telling the story of what matters to you?

Growing up, the woods were my haven. It was a place I could go to and feel wild & lonely in the most productive way. I’d follow tracks, catch tadpoles, collect empty buckshot canisters, climb trees, sing songs mournfully, set snares that never worked – the whole kid-in-the-woods gamut. Animals both seen & unseen were points of inspiration, things to dream upon, and sometimes, beings to become.

As Sarah Orne Jewett so rightly states in her novella The Country of the Pointed Firs, “In the life of each of us… there is a place remote and islanded; we are each the unaccompanied hermit and recluse of an hour or a day; we understand our fellows of the cell to whatever age of history they may belong.” I carry that wild space inside me still. It feels especially important now since I’m surrounded by more buildings than trees these days.

However, a few words about the city wilderness I’m experiencing now: I never thought I’d like living in New York City, but after three years, it’s become it’s own wild place I inhabit with love. There’s a different sort of wildlife here (rats, cockroaches, pigeons & feisty sparrows, tiny dogs, alley cats) that I’m interacting with and integrating into my new work.

"Animals both seen & unseen were points of inspiration, things to dream upon, and sometimes, beings to become."

Your chapbook Call It a Premonition is based on the Voynich Manuscript, a Renaissance-era text that to this day hasn’t been deciphered, much to the chagrin of linguists, cryptographers, and codebreakers. How did you settle on the interpretation of the manuscript as a collection of mini, experimental dispatches?

I had this teenage girl voice entering my poems for a while. Stumbling upon the Voynich Manuscript (which you can page through via Yale) seemed like a great opportunity to explore that teenage girl voice, reimagining the Voynich Manuscript as her diary. I had just gotten my first smartphone and was managing social media for a hunting & fishing app at the time, so my new awareness of digital presence enters the chapbook alongside this beloved yet nameless girl’s coming-of-age.

In your poem “The Way Back,” a horse “steady in the depths of his soft manured stall” finds a place in a poem steeped in loss. Why did you choose the horse to mirror the speaker’s pain?

I love horses. They are my favorite animal and have been my favorite animal since I can remember. As a kid, I wanted to grow up to be a horse instead of an adult. Instead I grew up to be an adult that stables a horse in any poem she can. I have immense respect for a horse’s perceptive powers. I’ve always seen them as healers; in poems and in real life, their beings are strong enough to act as a conduit for a person’s true feelings.

"I carry that wild space inside me still."

Back to dear Willicus. I know you said you are too close to her to write about her yet, but has she helped you write about the animals that do appear in your poems?

I so want to write a poem about Willicus, but it’s tricky for me to focus a poem on her. It’s like I’ve gotta build up my heart-vulnerability chops in order to capture her on the page. With the other animals that appear in my poems, there’s a distance there which allows me to manipulate them. They are what I imagine them to be. Willicus defies imagination.

Have you read a poem written by someone else that reminded you of Willicus?

Such a great but tough question! I think Frank O’Hara’s poem for V.R. Lang captures something of my love for Willicus and her formidable spirit.

"It’s like I’ve gotta build up my heart-vulnerability chops in order to capture her on the page."

What’s next for you on the poetry front? (More menageries, I hope!)

I’ve been working on a chapbook-length manuscript called “Body Mind” that investigates my relationship to the body. These poems are doing work to ground me (at least momentarily) back into the toes and fingers and guts and sex of a woman-person interacting with other persons. It’s been a challenge but a necessary one. One of the poems from this manuscript just found a home at Sixth Finch, and a few more will soon be out in Paperbag. And don’t worry – there are plenty of animals in these new poems!

A simile for Willicus?

She’s a light for all times.

Ruth Baumann: Feral Like Me

Ruth Baumann talks about the heart-opening work of caring for animals, how her two adopted cats helped her get some stability in her life, and her best advice on getting your poetry to stand out in the slush pile.

Ruth and I are working on a little theory: maybe all Ruths are ardent animal lovers. (Are you a Ruth and a detractor? Let us know so we can account for outliers.) Maybe one day we'll meet in person and it will be an instant Disney movie – animals EVERYWHERE. #TeamRuth

Here's the next best thing: talking to Ruth about the heart-opening work of caring for animals, how her two adopted cats helped her get some stability in her life, the feral nature of love and heartbreak, and her best advice on getting your poetry to stand out in the slush pile.

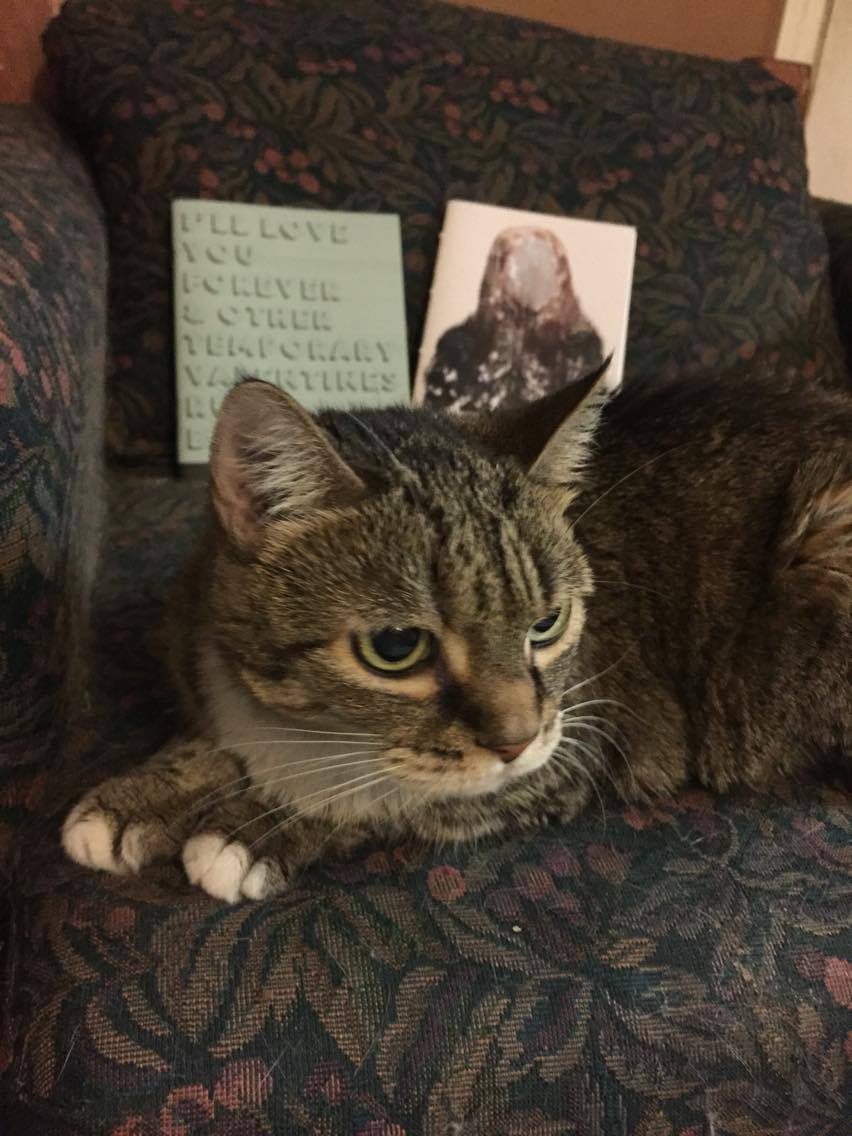

So now that you're biting at the bit to hear her do the talking, some background: Ruth Baumann is the author of three chapbooks: I’ll Love You Forever & Other Temporary Valentines (Salt Hill, 2015), wildcold (Slash Pines Press, 2016), and Retribution Binary (Black Lawrence Press, forthcoming 2017). Her poems have been published in Colorado Review, Sonora Review, Sycamore Review, The Journal, Third Coast, and others. She received an AWP Intro Journals Project Award in 2014. She holds an MFA from the University of Memphis and is pursuing her PhD at Florida State University.

Additionally, she is former managing editor of The Pinch literary journal, and she currently edits Nightjar Review with Tara Mae Mulroy. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with her two cats Julia and Autumn (and the occasional foster feline).

You mentioned that you adopted your cats Julia and Autumn from the Richmond SPCA when you were in a transitional period in your life. Was it the uncertainty of this time that made you seek out your cat companions?

I wonder about this—or, the bigger picture version: what draws me to animals, particularly cats? I’ve always loved animals, always gravitated towards that which watches, communicates differently, needs protection or translation. There’s something really comforting to me about the animal mind, about how wild & honest it is. I think it’s a sort of perpetual underdog empathy that comes from a billion sources & can be analyzed to death but never eradicated.

On a smaller scale: I was something of a delinquent youth (as I imagine many artists were), & I adopted the cats a little over 8 years ago, when I began to transition my life into stability. I think the turn into acceptance of a normal, non-chaotic life allowed me to open my heart back up, & to be able to care responsibly for animals. Anytime I’m not in fight-or-flight mode, I feel like the person I want to be, which is one that is useful & has a lot of love to give. The cats probably grounded me in this new life as much as I helped ground them in a home where they’d be loved (the little one, Julia, was an owner surrender multiple times before we fell in love, & I believe she’d been abused).

Also, I grew up with cats, & have consistently loved them—I’m the weirdo at the party who will go hang out in the corner with the resident cats rather than talk to y’all.

"There’s something really comforting to me about the animal mind, about how wild & honest it is."

Autumn

I love the biographical note left in Julia’s file when you first got her: “EVIL.” They didn’t even try to mince words, huh? Can you talk a little about how affirming the affection of a picky animal is? And what caring for animals teaches you about unconditional love?

Oh, so affirming! I’ve given it a lot of thought & Julia is pretty solidly my soulmate. (Or, one of—I guess we get a few.) Like I mentioned, I got them when I was in the process of shifting lifestyles, & any transition that requires letting down defenses & feeling what’s been numbed causes a lot of fragility. Fragility that’s been there all along, I believe, but has been masked. Julia in so many ways represents this me, the me that I still contain: she’s been endlessly loving to me from the first moment (she will sit by me sometimes & purr for hours on end, she is waiting at the front door whenever I come home—even if it’s just from a walk to the mailbox, etc.), but gets so instinctual sometimes. If someone pets her too soon, or if I pet her too much, or don’t pay attention to her body language, blood is shed (very literally). I had an ex she used to spit on—I’d never seen a cat spit before!

I believe that most creatures are like that, honestly: it’s just our hurts that block our unconditional love capacity. By whatever stroke of luck/fate, Julia recognized a kindred in me, & we bring out the best in each other. She’s mellowed a little bit over the years, too, believe it or not. (Autumn, too, is a fragile spirit—she was found on the streets at about a year old, & is incredibly skittish. Once she’s comfortable around you, she’s completely demanding of love & won’t stop purring & cuddling, but until then, she will—despite being a 17 pound calico—be impossible to find.)

I think unconditional love is easily taught by animals. I think perhaps more correctly, unconditional love is already inherent but animals remind us of it. There’s no fear of the hurt or trickery that can come from human relationships, really—a kitten won’t have control issues or manipulate you or drink too much or fall in love with a different person, etc. (I hope.) Taking care of animals also grants me a specific purpose in the relationship—especially in the case of the baby kitten I fostered recently & had to bottle-feed every few hours—which I think is a lot of what we want as humans, to feel love (not just towards us, but to feel love outwards) & to feel useful. I’ve heard a lot over the years about love being not a feeling but an action, & taking care of animals is a great way for me to practice this.

"Unconditional love is already inherent but animals remind us of it."

Ruth and Julia

To thread the needle of the last question, let’s talk about your poetry through the lens of unconditional love. Does it play a role in your work or how you engage with your subject matter?

That’s an interesting question. I wish I could say yes, but so many of my poems have come from my wounded places, from my difficulties with trauma & human relationships & reconciliation with my past that I’m not sure they deal in unconditional love as much. They try to. They try to wade through the conditions they were taught, & they try to learn to love themselves & others as best they can. I guess my poems are as fallible as their writer. While there are moments of light in the poems, they’re often more concerned with seeking & broadcasting the truth than a particular kindness or love.

Poetry is often a safe space for me, as all written language is, to work out the pains that can’t be expressed healthily or comprehended in a particular relationship (often the relationship between self & universe). Maybe I can reframe this as unconditional love for self being an unspoken tenet of writing at all—that there’s some hope, some flicker of survival that wants to be love underneath every attempt at communication, growth. Otherwise, why bother?

Even in your poems, the speaker can’t stop thinking about the wellbeing of the animals that populate the lines. Examples: in “Loving You Terrifies Me,” you write: “Your fear is waking up with a raccoon in your face. My fear is / the poor animal will realize there’s another side” and in “In Media Res,” you write: “Scientists are killing one species of owl to allow another to survive. / I’ve forgotten to read the news for a decade. Promise love isn’t a series of / selfish confessions? Did anybody ask the owls?” Would you say that’s a confessional impulse at work?

Oh, of course! Probably all writing (& all actions) are confessional, really. Also, I literally was dating someone once that had a wild animal in his attic. Every night we’d go to bed this one winter & hear scratching above our heads. This was years before I fell in love with raccoons, of course, so I didn’t befriend him/her. That anecdote isn’t really that useful, but it’s confessional, too.

I don’t know anything beyond my own experience, I think. I mean: I can understand many other things, I am guilty of having way too many opinions sometimes, I can sympathize & empathize with others, etc.—but all that I can truly speak to is that which I have been through. I try to be mindful of never speaking for that which I’m not qualified, & I’m sure this reflects in my poems.

"I identify with the sense of watchfulness, the wariness of animals."

Ruth bottle-feeding Luz

I was so heartbroken to hear your little foster kitten Luz didn’t survive, but I’m moved by how deeply you cared for her in your short time together. Can we expect to see a poem about Luz in the future?

Yes. I’ve already written her into some. I also dedicated my full-length manuscript to her. Luz meant a lot to me because she was ridiculously perfect, & I’ve never been in that much of a mothering position before: it’s impossible (at least for someone like me) to not attach deeply to an animal you wrap up in a washcloth & bottle feed & tuck in with a heated blanket every few hours. (I mean—did you see the pictures?) I also was going through a period of some loss in my personal relationships, & having an animal to love deeply & claim as family was really crucial to my healing at the time, to my remembering & walking back into the depths of my capacity to love.

Animals show up quite a bit in your work, especially when you write about love and heartbreak. How are these ideas linked for you?

We are animals! I think humans forget that far too often. We are animals, pack animals at that. As much as it may seem that our consciousness separates us, & our laws & rules & ideologies do, I don’t think we’re that far off from the other species. We are just one animal on the planet, & it gives me peace to remember this. Also, as a writer, as a Pisces, as an introvert, etc., I identify with the sense of watchfulness, the wariness of animals.

In terms of love & heartbreak, I believe these are some of the most deep, visceral emotions we can experience, & I’ve often felt intensity that seems wild. If you’re a poet & you don’t claim you’ve felt feral before, I’m not sure I believe you.

"If you’re a poet & you don’t claim you’ve felt feral before, I’m not sure I believe you."

Autumn

You’re the author of three chapbooks: I’ll Love You Forever & Other Temporary Valentines, wildcold, and Retribution Binary. What about the shorter form of the chapbook appeals to you? And your best tip for putting together a chapbook?

I think maybe my attention span? It’s easier for me to write a cohesive body of work when it’s shorter. I’ve actually written some longer manuscripts, but they usually eventually end up feeling too disparate—it’s really difficult to pull together a full-length book’s worth of poetry that connects from the first to last page.

The best tip I have for putting together a chapbook is to print out everything you’ve written lately (lately being a relative term) & spread it across your floor. Then I pile together the poems that make sense with each other, the poems that speak to each other, & see if the pile(s) are big enough to attempt a larger endeavor like a chapbook or book. Usually, poets have obsessions or work through something for long enough that there’s a thread through a season’s worth of work, I think.

Fill in the blank: when you’re reading through piles of slush, the work that most catches your attention…

Has a moment of truth. Has a break into clarity. Says beautiful things that have meaning, gives as much credence to the message as to the delivery. Reminds me of an old self or a new way to look at my current self or a self I want to be.

"My cats are like an affirmation from the universe."

Meta Julia

If cats were a poetic form (e.g., sestina, sonnet, ode), they’d be…?

Free verse! Would you try to contain them?!

A simile for your cats?

This stumps me. I want them to be metaphors. My cats are like an affirmation from the universe.

Sonya Vatomsky: Hierarchify Your Love