Amie Whittemore: The End of an Era

Lovers, I hope you're as excited about the first-ever interview in the Pet Poetics series as I am, and what a way to kick it off. I got the chance to chat with Amie Whittemore about her cats, the specific way grief works when a pet dies, and her advice for writing about that loss in a meaningful way.

Before we dive in, a little about Amie: she is a poet, educator, and the author of Glass Harvest, forthcoming from Autumn House Press in July 2016. She is also co-founder of the Charlottesville Reading Series. She holds degrees from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (B.A.), Lewis and Clark College (M.A.T.), and Southern Illinois University Carbondale (M.F.A.). Her poems have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Sycamore Review, Rattle, Cimarron Review, and elsewhere. She spent a year photographing her former cat Stevens every day as an experiment in affection and Instagram filters. She lives in Charlottesville with her cats Chicory and Sage.

First of all, Amie, I'm happy to hear your cats Chicory and Sage are finally letting you get some sleep. Tell me about your decision to bring them into your life.

About a year ago, my beloved cat of ten years Stevens (yep, she was cat Stevens) died. As the first pet of my adulthood, adopted the year two grandparents died and lost the year after I divorced, her death marked not only a grievous loss, but also an end to an era of my life. She felt like the last anchor holding me steady; once she was gone, I felt entirely unmoored.

As anyone who has felt unmoored knows, it is largely impossible to imagine feeling moored again. Yet, with time, fantasies of kittens began to frolic in my mind. Having spent a decade fretting that Stevens was excruciatingly lonely as a single cat, I decided to adopt two kittens this time around. I began haunting the SPCA, waiting for love at first sight.

I met Chicory on one of these visits. She mewed at me as I passed her cage. I picked her up; she purred immediately, completely at ease curling up in my lap. A four-year-old boy sat on the floor next to me and informed me this kitten’s name was George and he was going to take her home when his dog died.

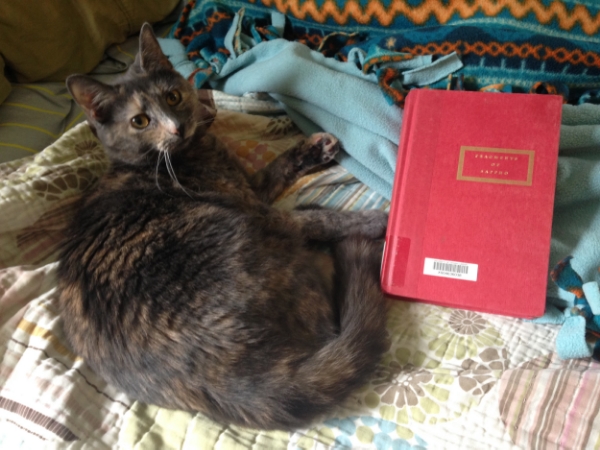

However, Chicory (whose middle name is George, in honor of her almost-owner) was there two days later when I decided I needed her in my life. That’s when I found a calico companion for her in Sage. Where Chicory is confident, charming, sociable, and playful, Sage is timid, frenetic, and (strangely enough) aggressively affectionate. They are loving and standoffish with each other in turns. I find their personalities, and their relationship, intensely interesting.

“As anyone who has felt unmoored knows, it is largely impossible to imagine feeling moored again.”

I know you lost your cat Stevens not long ago, and you reference her death in your poem “Year In Review." The line "Grew weepy in conversation about said dead cat / more often than is culturally appropriate" struck a chord with me. Did you feel pressure to meter how you wrote about her death because of the "culturally appropriate" expectation?

The poem picks up on the pressure I felt to withhold the intensity of my grief when friends politely shared their sympathies with me. Even recalling that grief brings tears to my eyes. There is not a day I do not miss Stevens.

I also think my poems about Stevens address a larger issue regarding grief in American society. I do not think we know how to honor it well in each other. We rely on tropes like “time heals” and “you’ll get over it,” though I think, in all our hearts, we know there is no “getting over.” And time may heal, but scars remain.

I think we could learn something from our pets about handling grief. They are such good caretakers of us in times of sorrow. They do not judge our weeping. They cuddle with us. They do not put time limits on feelings.

How did writing about Stevens help you process the loss? I'm thinking specifically about your poem “Song for Stevens” where there's heartbreak in every line. I can hardly read this without tearing up: “If given seven slides of calico hides, / I’d know which side was hers. If blindfolded / and handed seven cats, I’d know her by shape.”

I can’t read those lines without tearing up either. I wrote “Song for Stevens” while she was still alive. Writing that poem, and the poems that confront her death, helped me to honor the unique experience of adoring a pet. These poems give voice to the unbearable—and breathtaking—need to love something else unconditionally, passionately, and thoughtlessly. We have such a hard time doing this well with each other. With pets, we can learn to do this better—for their sakes and for the sakes of our relationships with our partners, families, friends, and all the creatures we with whom we share this earth.

“I think we could learn something from our pets about handling grief. They are such good caretakers of us in times of sorrow...They do not put time limits on feelings.”

What's your writing process like, and do your pets ever figure into it?

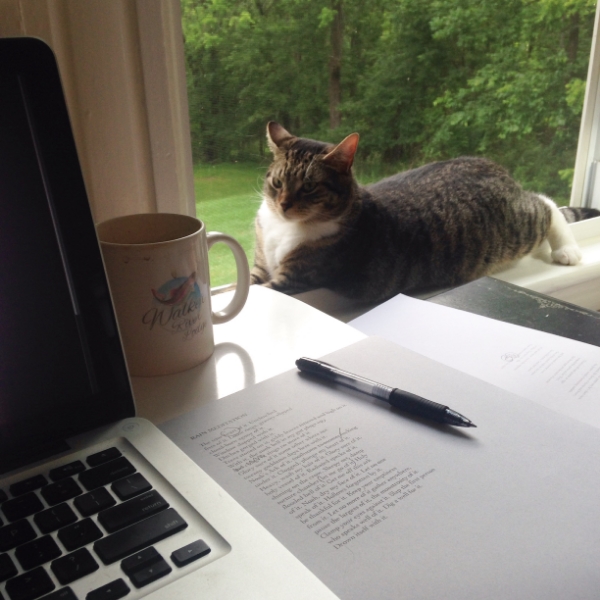

My cats are active writing partners! I usually write in the morning, which is one of their favorite times to play. My writing time is interspersed with crumbling up paper balls to toss at them while I work. Usually one decides to stroll across the keyboard to make some edits. One is usually perched in the window beside me or on a printed poem—drafts make great beds, apparently!

Your debut poetry collection Glass Harvest will be out soon (and I can't wait to read it). Do you have some advice for poets who are trying to complete or publish their first book?

Some of the most bolstering advice I received was from the poet Jane Hirshfield when I took a workshop with her at the Key West Literary Seminar. She said to treat every rejection as a gift of time—time to help the manuscript become its best self. I worked on this manuscript for eight years. It was not always easy to see rejection as a gift; however, when I recall its past selves, I’m incredibly glad they did not get published.

Poetry publishing is all long game. And it can feel even longer when you begin to compare your journey to Poet X or Poet Y. Try not to—or, indulge your envy, let it know you hear it, you understand its fiery pain, then move on. Try to remember comparison is the thief of joy. It is the thief of your very life.

“Try to remember comparison is the thief of joy.”

Fill in the blank: you're stuck on a poem, so you…?

Ignore it. I’m always working on multiple poems at a time, so when one is being disagreeable, I focus on others and let my subconscious chew on the stuck poem awhile. Or, I “break” it, tackling the subject from a different angle, trading narrative for lyric, long for short. I try to notice where my attention drifts and cut those parts. If I’m bored or restless, no doubt a reader is, too.

What is it about the animal world that most captures your attention as a poet?

I love learning about animal societies. I’m working on a poem about albatrosses and discovered that they spend years crafting complex courtship dances. Once they mate, the mates abandon the dance and form a private language, discernible only to each other. This is amazing to me and seems profoundly similar to human partnership: every long-term couple I know also has its own private shorthand.

Advice for poets who want to write meaningfully about the death of their pets but don't want to be dismissed as sentimental?

The advice is the same as what I would give for writing about the grief of losing a beloved human: be concrete. Focus on the specific interactions you have with the pet, the specific expressions of its personality. Don’t be afraid to be humorous. My favorite memory of Stevens is of her lying on my face and neck at 3 a.m., a ball of purring sweetness, while also drooling all over me. Include the drool with the purrs and you’ll be in good shape.

A simile for your cats?

Oh lord, I’m such a poet; my cats’ names are metaphors for themselves.

Chicory is an invasive weed in Illinois where I grew up—incredibly hardy, able to grow along roadsides and in pavement cracks. Chicory the cat is the same—hard to imagine her not thriving wherever she goes.

Sage is much like the spice—unique. Flavorful. And, as with the spice, which I rarely use but love the scent of, I don’t quite know what to do with her most of the time.