Gretchen Marquette: The Last Time We Were Strangers

Poet Gretchen Marquette on her life-making relationship with her dog Lucy, the creative process, Rumi's love dogs, and what animals have taught her about vulnerability.

I'll keep this short because I want you to experience Gretchen Marquette’s love stories about her dog Lucy and her insight on the creative process right now. But I will say, if you haven't checked out her first book May Day yet, do it. It sticks with you.

About Gretchen: Her work has been featured in Poetry Magazine, The Paris Review, Tin House, Harper’s, The Literary Review, PBS NewsHour, and other places. Her first book, May Day, was released in 2016 from Graywolf Press. She lives and works in Minneapolis.

Tell us about Lucy and your 14 years of companionship with her. Some favorite moments, memories?

I brought Lucy home on Mother’s Day in 2003. Lucy (then named Minnie) had been living at a shelter for six months, and was a little over a year old. I’d gone to the Humane Society with a friend to see if they had any rabbits, but while we were there, he convinced me to look at the dogs, and the second I saw her, I knew she was mine. I visited her several times, and went through the long application process they required, but eventually I was there handing a green leash over to the woman behind the counter. She said, “This morning I told Minnie that she’s finally going to her forever home.”

Now that I’ve written that, it sounds saccharine, but it wasn’t. Lucy had shown up there in pain and a little underweight, and watched her littermate be adopted and disappear three days into her own six month stay. She arrived knowing no commands, and with an infection in her leg so bad she couldn’t step on it. She wasn’t spayed, and didn’t know her own name. I didn’t know it yet, but here was a dog that wanted to be touched all the time, and she had gone so long without any consistent affection. And all of that was over for her. She did have a home.

There have been dark times in my life, but rescuing Lucy and giving her the love she wanted is one thing I know I’ve done right, and one reason I’ve been glad I was alive to help her. We’re getting into an It’s a Wonderful Life moment here, which is the opposite of trying to prove all this isn’t saccharine, so I’m going to stop there.

When I took Lucy outside of the shelter, she was too afraid to get in the car. It turned out she was afraid of everything. While we stood there, a strong wind blew, and she cowered in the grass and peed. It had been so long since she’d been outside, and her entire puppyhood had been spent in a small outdoor kennel. I knew I had to lift her in the car, but I was afraid, too. Would she bite me? It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since.

It’s hard to pick the stories I want to tell about my life with Lucy – I could write pages and pages, and this is especially true because until July of 2014, there was another dog with us – my husky, Sage. Sage and Lucy were not very close most of the time, but were partners in crime when it came to getting in trouble – running away in particular.

Once, I got a phone call from an unknown number. It turned out that someone had left the gate open at the house I was renting, and my dogs had gotten out. Lucy is a Treeing Walker Coonhound, but when the woman said, “I have your beagle I think?” I knew it was Lucy. “My husband is trying to catch your husky,” she said. I was two hours away, so I told the woman my address and asked if she would put the dogs inside (I left my doors unlocked in those days), and she said, “Honey, these dogs have been down to the river rolling in dead carp and they are covered in it.” When I showed up at home, I saw for myself. It was the foulest thing I could imagine, but they were both so happy. Still, it was a night of a thousand baths.

Lucy has always been a good friend to me; she’s very tuned in. One night, I woke in the worst pain I had ever felt. I would have a root canal later that day, but when I woke, I didn’t know what was going on, and it was 3 a.m., and I was afraid. My boyfriend told me to relax and not get upset because it would make it worse, and then went back to sleep, but Lucy sat up with me for hours while I cried on the living room floor. At one point she came and sat right in front of me, and I put my arms around her and cried into her neck, and she sat there and let me do that for as long as I needed. It was a profound experience of being loved and comforted – it’s for that reason that of all the thousands of days I’ve spent with my dog, this is one I choose to tell you about.

"It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since."

In your book May Day’s dedication and in your interview with Kaveh Akbar on Divedapper, we can see that you value your friendships: “I don’t think I’d be here if it wasn’t for those friendships. Which is strange because we give such a privileged place for romantic love and familial love, but in both of those forms of love you are under a contract in some way. But then you have friendships, which have actually been some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had in my life.” Do you count Lucy among these life-saving relationships? Or do you consider that relationship more familial? I’m always curious about how folks think about their relationship with their pets.

My relationship with Lucy is definitely a life-making/life-saving one. She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman. I realized recently that I’ve spent more time with her than I have with my siblings.

One thing I hate is getting in the car for a long drive home alone. Especially at night, but really any time. Having Lucy in the back seat makes it suck less. She’s lived in three states with me, and at nine different addresses. She was there when my brother deployed (twice) and when my partner left (also, unfortunately, twice) and she was there when my niece came home from the hospital and when I came home after signing the contract for my first book. I know she hasn’t “shared” in these moments in the way a human being could have, but she accompanied me through them in a deep way and I’m grateful.

"She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman."

I love that your dogs show up in your first poetry collection May Day (Graywolf Press, 2016), like in the poem “Powderhorn, after the Storm.” This part is one I think most people with dogs can relate to (maybe too well – I winced remembering times I had lost my temper with my now-dead dog Pete; I think that regret will follow me a lifetime):

I jerked her leash, nudged

her through the door

with my knee. These cruelties

aren’t held against me.

I regret them deeply.

What is it about documenting regret in a poem that appeals most to you?

Sage

I suppose I felt like it was important to be honest about that night, and losing my temper with Sage was part of it. I didn’t know it until I had time to process it later, but I was irrationally angry at her that she was sick, and I knew that she wouldn’t be with me much longer. I was terrified to think of losing her. I’d raised her from a six-week-old; she’d been in my life since I was nineteen.

I had also just had a terrible, frightening day, and I wanted so much to be asleep. She’d woken me up, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to fall back asleep. The power was out everywhere and it was hot, and there were constant sirens. I still regret it. Sage was such a good dog. She deserved so much better that night. Letting myself off the hook in that poem would have ruined it.

So much of May Day is in conversation with the interiors grief creates (to quote one of many examples, in “About Suffering”: “there are so many / places for grief to live that we can’t note each address”). These poems trace the ending of a romantic relationship, the worry over your brother who was deployed to Iraq. And it seems that animals are a language for grief in this collection – the deer wandering through these poems (which we’ll talk more about in a bit), the macaw and painted turtle, the cardinals in the poem “Red.” Can you talk a bit about how animals helped you excavate this rawness, this vulnerability in your work?

I lived outside of a small town in a wooded area, and there were animals everywhere. There would be hoofprints in the sandbox some mornings, and the railroad tie retaining wall behind our house was full of toads. There were skunks, and raccoons, chipmunks and squirrels – I saw them every day. Sometimes terrible things happened to these animals. They got sick and died. They killed each other. They were hit by cars. I don’t remember processing any of this, but my dad told me that when I was two, I would remind him, every time he drove away from the house, not to “bump the deers.” So their well-being was an early concern. They were vulnerability personified.

I also think (and this might have to do with my deer imagery issue as well) that watching a deer skinned and dressed in my neighbor’s yard when I was small was shocking and transformative in a huge way for me. For one thing, it changed how I thought about bodies, including my own.

I have used this quotation many times in connection with stories about what might have led me toward poetry, but it has never stopped feeling right to me. Alan Williamson says that, “for many of us, the moment when we experienced something we could not share with our outer world, because our outer world had given us no 'word' to acknowledge it, was the moment that impelled us toward poetry. And poetry was a struggle with the given language, to make it give us better words than 'unlikely' for what had fallen out of this world’s likelihood.” I think that’s the truest statement I’ve ever read, and my earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals.

"My earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals."

True or false: To love is to grieve in slow motion.

False. I feel they are separate. I’ve actually spent a lot of time thinking about this! I prefer to think of grief as being powerless to negate or eliminate beauty or joy, and I’ve also accepted (more or less) that beauty can’t eliminate grief. Grief is not going anywhere – there’s always more to come. But there’s a good insurance policy in that. If grief and joy can’t touch each other, joy is protected, and there will always be more of that, too.

Lucy is going to be sixteen years old in December. In August, they thought she had a mass in her bladder, and for a few weeks I was wiped out with sadness and worry. It turned out that wasn’t true, and now she’s healthy again. But I know she can’t stay forever. Every day, I cook ground beef and mix it with pureed pumpkin and mix it with her dog chow, to help keep her weight up. Every day it makes me happy to watch her eat. She wags her tail the entire time.

When I was reading May Day, I started noting in the margins “Gretchen’s deer” whenever one popped up. Let’s look at “Deer Suite” in particular, where the deer is directly tied to the theme of want that drives so much of this collection:

If I say my longing is a doe,

that it bounds,

that it chokes, has parts that splinter,

that it can be split

from breastbone to pelvis.

(I love how seamlessly this connects to the epigraph in “Doe,” a poem that appears earlier in the collection: “A Wounded Deer—leaps highest—” from Emily Dickinson.) Let’s talk about longing and want and when you first realized that theme would shape this book.

I think that theme has shaped everything I’ve ever written and will continue to do so. About a third of the poems in May Day were taken from my thesis. At the time I was really interested in those lines of Rumi’s – “There are love dogs / no one knows the name of. // Kill yourself / to be one of them.” I heard another poet use them once in the spirit of romantic adventure and they rang a little false to me. I don’t think we all get to be love dogs.

The poems I was writing during graduate school were about the partner I was in love with, and about Lorca, and about my little brother who is a soldier. They were about my own broken heart. I wondered if we were all love dogs, and if the condition of being one comes and goes, or if it really is a choice, as the poet I mentioned above seemed to think it was. I still don’t know. But this idea of longing plays into that directly.

During graduate school I wrote a poem called “Love Dog” (and, in fact, that was the title of the manuscript I first turned over to Jeff Shotts). The poem was about the first dog I ever met who was afraid of me and didn’t want to be touched. It was the dog that belonged with the family who bought our house in the woods. I had reached out to pet the dog and she growled at me. Her boy held her collar and apologized, and then said, “Some people hurt her for fun,” and then told me that she had been a stray, and that someone had shot her with BBs and they were still under her fur when they found her, running loose.

I realized there was nothing I could do to prove myself to this dog, and I saw myself for the first time as an unknown quantity to another creature. That I had the capacity to hurt someone else. She didn’t get to be a love dog. Things have happened in my life that have made it harder for me to be one, too. Is that a failure of courage or character? I don’t know.

Even though this seems to be getting off topic, I don’t really think it is. I want to be a love dog. I long to be one. And sometimes I feel like I am killing myself to be. But what I really wish is that I could be a love dog and also not kill myself.

"I don’t think we all get to be love dogs."

What are you absolutely obsessed with right now? It can be anything, not necessarily poetry or animal related.

I’m obsessed with cave paintings, with the spacetime continuum, with images of The Madonna, and with origins of human mythology and our earliest attempts at situating ourselves in the world. (I’ve been reading Joseph Campbell.)

What’s changed the most for you since your first book came out?

I suppose that it’s been an adjustment to realize, after so many years, that my poems have an audience. For so long it was just my classmates and my teachers. I’ve met new people because of my book; it’s brought friends and opportunities into my life. In some cases, it gave me a deeper home in poetry, and a chance to connect with other poets I deeply admire – some new to their audiences like I am, and others who have been heroes a long time.

Advice for poets staring wildly at the expectation of a second book and coming up short?

I’m working on my second book, too. Some days I feel like I have an answer for you, and some days I want you to tell me what others have to say on the subject!

I know that for me, the process is different than it was when I was writing May Day. I’m much farther removed from my academic community, and I’m working differently because my life as a poet has changed (see above). When I’m writing a poem I have to remind myself that each one deserves its own space. Every poem won’t make it into the book; I have to let the poems arrive, whatever they’re about and whatever form they want to take. That said, it is fun to watch a book arrive slowly – to see themes and motifs materialize. It helps me understand myself and the life I’m living.

I would say trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something.

It’s also a good time to rest, especially if your book just came out. I like intentionally taking time away from writing and using that time for reading. Collections of poetry are always inspiring, but nonfiction books also bring a lot to the surface for me. I just work hard in my writer’s notebook–taking notes, jotting down ideas or lines, etc. During my writing vacations, either what I read will inspire me, or the obstinate part of my brain that’s been told it can’t write for ten days will suddenly find itself very active. It works most of the time.

"Trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something."

A metaphor or simile for Lucy?

Lucy is my home.

Daniel M. Shapiro: Rules You Never Considered Breaking

Poet Daniel M. Shapiro on his pupper Pepper, how a poem has changed his mind before, how he makes editorial decisions, and why he avoids writing about certain topics.

I'm still grieving the election results hard, and I don't know what to say other than I don't want to think about silver linings or "bridging the divide." (You don't get to threaten the majority of Americans and advocate for our oppression and demand that we respect "different opinions." Nah. You get to have an opinion about a favorite ice cream flavor, not the persecution of entire communities.)

But I am grateful for people like Daniel M. Shapiro who remind me that the world isn't a complete garbage can. Thanks, Dan.

Daniel and I spoke before the election, so we don't get into that here. But I know my dogs have been a reliable source of comfort since Tuesday, so I'm glad we get the chance to honor our small companions and talk about poetry because, dammit, something has to get us through.

A little about Daniel M. Shapiro: he is the author of Heavy Metal Fairy Tales (Throwback Books, 2016), How the Potato Chip Was Invented (sunnyoutside, 2013), and The 44th-Worst Album Ever (NAP Books, 2012). Some of his recent work has appeared in Ink in Thirds, Bitterzoet, Uppagus, and Forklift, Ohio. He is a senior poetry editor and reviews editor for Pittsburgh Poetry Review, and he interviews poets at Little Myths.

Tell us a little about how your pupper Pepper came into your life.

Our 13-year-old golden retriever, Heidi, had died more than five years ago, and I was distraught to the point of telling my wife, Kris, that I didn’t think I would want a dog again. Previously, we had discussed getting a cairn terrier, but I had wanted a rescue dog and thought it would be unlikely to find a cairn that way. A couple of weeks after Heidi died, Kris sent me a link to a cairn rescue home page with a picture of an absurdly cute dog, and she wrote, “Maybe we could get one like this sometime.” Even though I had sworn off dogs, I wrote back: “I don’t want a dog LIKE that one. I want THAT one.” So we drove a couple of hours to Ohio and picked her up. She was wormy and weighed 2 pounds. She looked like a Beanie Baby.

What’s the biggest perk of having a dog? The biggest drawback?

The biggest perk is that you get to have a family member that provides unconditional love. She’s perceptive and knows when people need to be left alone or want cuddles or kisses. I don’t think there are any major drawbacks. I don’t like having to board her when we go out of town, but that’s probably it.

Has Pepper had any influence on your writing? If so, how?

I think she has influenced me by helping to provide a comfortable setting. I always write in the same chair, I always put my feet up on an ottoman, and she almost always lies there on top of my legs. She contributes to the right mindset to write.

"I don't want my poems to suggest I have lived or felt things that belong to other people."

If you had to describe your poetry wheelhouse – topics you’re most likely to write about – what would it be? Anything you try not to write about?

My wheelhouse is typically rock or pop music, but it has included other elements of pop culture. I have some new poems based on board games, for example. I try not to write about topics or themes I’ve seen repeatedly, such as nature. I feel like I would be competing against everyone else who has done that, and I wouldn’t have anything to add. I also avoid topics I’m interested in but don’t believe I’m the appropriate speaker for; I don’t want my poems to suggest I have lived or felt things that belong to other people.

True or false: a poem has changed your mind before.

Probably 10 years ago or more, I started to read books by Russell Edson, James Tate, and others who blurred the boundaries between poetry and prose. They broke what I had considered to be rules I never would’ve considered breaking, and their poems encouraged me to be more open to whatever structure or odd subject matter suited my needs as a writer. Now I write more prose poems than anything else.

As an editor for Pittsburgh Poetry Review, you’re no stranger to slush. What are the hallmarks of a poem you’d want to publish?

I am drawn to poems that express the individuality and/or specific obsessions of a poet but that covertly reveal an element of universality. I find that a lot of writing uses the opposite approach; it’s more dedicated to universality, and the unique ideas or experiences of the poet are secondary. The latter scenario can create a sameness in the submissions we see.

One of the best poems we’ve published in PPR was about baseball, but of course it wasn’t about that only, and you could argue it wasn’t about it at all. The poet blended her love of baseball with the culture of where she grew up, her adolescence, her relationship with her father, etc. So I got a sense of why only that poet could write that poem, but the drive of the language, combined with “America’s pastime,” provided a broader appeal, as well.

"The best poets can rearrange topics I tend to avoid—e.g., religion, which usually inspires a kind of emotional shorthand—and find something in the topics I never would’ve seen without their help."

And a follow up: any pro tips on checking an aesthetic bias while reading submissions?

If a poem covers a topic I think has been done to death, I focus on the poet’s approach. Are the trees really trees? Maybe a poem starts as a conventional tree poem, but the trees become vengeful and start to kill people who are ruining the environment. Turn the tree poem upside down, and I’m there. If it’s a dead cat poem, will it become a zombie cat poem (please?)? The best poets can rearrange topics I tend to avoid—e.g., religion, which usually inspires a kind of emotional shorthand—and find something in the topics I never would’ve seen without their help.

What do you think is the best poem you’ve ever written and why?

I don’t know if it’s my best poem, but my favorite poem I’ve written is called “Don Knotts Returns to His Hometown of Morgantown, W.Va., 1982.” I like it because people always laugh when they hear the title, but eventually they realize the poem is quiet and sad. I like how the poem can be many things: silly, poignant, surreal, journalistic, etc.

A metaphor or simile for Pepper?

Pepper is like a neighborhood bar: occasionally deafening, filled with love, on the verge of a pratfall, and all-out fun until she winds up in a deep sleep.

Megan Peak: Something Other than Myself

Poet Megan Peak on self care, bridging the gap between thesis and manuscript, and poetry's role in effecting social change.

I don't know about you, but I've been keeping my eye on Megan Peak, a hella smart writer who is already penning some of the most memorable poems I've had the good fortune to read. She's bound to do amazing things over her career.

And so as a Halloween treat (no tricks), you get to spend some time with Megan and her dog Radish. We chat about how Rad helps her put self care first (and how writing is part of that process). We also discuss bridging the gap from poetry thesis to book manuscript and poetry's role in effecting social change, including dismantling rape culture.

I told you – all treats.

A little about Megan: she received her MFA in poetry from The Ohio State University, where she was former poetry editor at The Journal. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming from Blackbird, DIAGRAM, Four Way Review, Indiana Review, Muzzle, Ninth Letter, North American Review, PANK, The Pinch, Ploughshares, Sou'wester, Tupelo Quarterly, and Valparaiso Poetry Review, among others. She lives in Fort Worth, TX with her partner and her dog Radish. You can find her at www.meganpeak.com.

Tell us a little about Radish and how she came into your life.

My family has always had pets. There hasn’t been a time in my life when I didn’t have an animal of some kind as a part of my daily experiences. So, when I moved to Ohio from Texas for my MFA, I felt that void intensely. And, if I remember correctly, the five of us poets in the incoming MFA program were some of the most heartsick people—all coming from some personal grief: break-ups, homesickness, sheer loneliness. But, as the year went on, I was comforted and enlivened by my cohort, my professors, the act of coming to the page day after day, the poems. So, when I rescued Radish in my second year at OSU and she was the one mistreated, malnourished, fearful, I was ready to tend to something other than myself. She taught me a great deal about relearning how to trust and practicing patience.

From what I can tell, Rad is part Chihuahua, part Miniature Pinscher. The people at the shelter named her Radish, and I couldn’t agree more with the name. She has a little kick to her—bold but sweet. She’s fiercely loyal, smart, and resilient. I think she misses the snow and the longevity of the Ohio winter, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter because she is such a mama’s girl. She is happy wherever I am. She is sitting on my lap right now, belly thick and rhythmic with whatever little dream she is having.

"I was ready to tend to something other than myself."

Throughout these interviews, I’ve talked on and off about my experiences with Dog Magic. It’s difficult for me to picture how much different a person I would be now if it weren’t for my dogs. (For example, my dog Pete is the reason I became a vegan. She’s also the reason I’m a very reluctant traveler. She hates traveling.) Have you noticed any significant way your life has changed because of Radish’s companionship? Has she impacted your writing?

I think, with Rad’s help and the outright passage of time, I have become more aware of my need to balance self-care with that of comforting others. What I love about Radish is that if she doesn’t want to be crammed on the couch with my partner and me while we watch a movie, she will jump down and curl up in her bed. I love that independent impulse in her, knowing when she needs us and when she would like to have some space. There have been times in my life when that boundary has been slippery at best, and when I notice these small moments with Radish, I find some affirmation in my impulses to be alone, to reach out, and/or to serve others.

Going off of that, one of my needs is to write. So, Radish does influence my writing, I suppose, indirectly. Writing exists, for me, as a form of self-care because without it I become anxious, overwhelmed, unable to process my surroundings and the events in my life. She aids in that ritual of returning to the page each day.

What’s one poem you couldn’t have written without a spark of inspiration from the animal world? What unexpected place did it take the poem?

Actually, my whole second manuscript that I am currently working on draws directly from the animal world. Egrets, horses, does—the project emerges from the strange connection between sisters and place and what drives one away from and back toward family. The manuscript explores the wild and the domestic, the exterior worlds of New Orleans, of swamps, of the Texas plains and the interior spaces of the home. It focuses on the female experience of marriage, of sacrifice, of daughterhood and sisterhood. The project attempts to examine that very tender, wild thread that links sisters as they bear witness to each other's trajectories. Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual.

One poem, “The Egret Bride,” which was recently published in Iron Horse Literary Review, is one such piece. It was one of those pieces that had no title, that began after reading someone else’s work (Kiki Petrosino, I think!). Ultimately, I found a way to speak about marriage, what one might lose in that union, and the ways in which family influences our choices. The poem documents the speaker watching as the sister transforms from girl to egret, from daughter to wife, from connected to estranged.

"Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual."

You graduated from OSU with an MFA in poetry last year (belated congratulations!). I don’t know if this is true for you, but I graduated expecting to just shop around my thesis as my book and that would be it. But after sitting with it for a couple months and even after getting a few finalist bites, I realized I still had more work to do before the thing was a legit manuscript for me. What has your experience been like? How much distance is there between your thesis and your current manuscript?

Oh, I definitely feel that. I knew the thesis wasn’t where I truly wanted it to be after my defense. My professor and mentor even said, “You have a thesis, but now we need it to be a manuscript.” I’m a perfectionist, so I don’t know if it will ever really be “done,” in my opinion, but the fact that I am comfortable moving on to this second project is a good sign that the manuscript is in the right place. And yes, the manuscript is pretty different than the original thesis—different title, different order, new poems, all of which has created a more compelling arc than what I originally had. Here’s to hoping that it won’t be a bridesmaid for much longer!

Your biggest, most ostentatious poetry goal that you may not even want to publicly admit? Here, I’ll share mine: I want to win a freaking Pulitzer one day.

Oh, goodness. I suppose I would love to be financially stable from my poems and books one day, to be able to rely solely on my writing as a source of income. I don’t know if that will ever happen with poetry, but one can dream. On a broader note, my partner and I are working on a graphic novel together, and I would absolutely LOVE 1) to finish it and 2) to have some network like HBO pick it up. That would be the life.

Several of your poems are about sexual assault: “Elegy with a River Inside It,” “What I Don’t Tell My Mother About Ohio,” and “When Asked If I Said ‘No’.” How do you balance the beauty of language when writing about something so violent and traumatic?

I’ve always remembered this quote by Plath from her journals:

“Some things are hard to write about. After something happens to you, you go to write it down, and either you over dramatize it, or underplay it, exaggerate the wrong parts or ignore the important ones. At any rate, you never write it quite the way you want to.”

The poems that you mention and others that address assault and sexual violence came from this very raw and unhinged place at first. Just me trying to get it down on paper. And yet, they never felt “right” or “done” or whatever you say in terms of finishing a poem. People in my workshop never really knew what to say about them, except that it was brave or important or necessary work. While it was nice to hear, it wasn’t helpful. So, I had to find my own way to frame these poems, and that usually emerged by juxtaposing the “drama” or trauma of the event with the violent beauty of place, environment, weather. I think it helped me, and I suppose the speaker of the poem, to fluctuate the lenses on these traumatic moments, which felt truthful to the experience and gave the poem / reader perspective.

"Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict."

And a headier follow-up: what role do you think poetry has in changing rape culture?

Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict. Even now, we have poets writing necessary pieces ranging from race and gun violence to the injustices of the current academic job market in regards to contingent faculty. So, I think poetry has and always will have a vital role in bringing awareness to cultural and social trends and issues.

Will my poems change rape culture? I don’t know. But magazines publishing these pieces like Vinyl, Winter Tangerine Review, Tinderbox Poetry, The Adroit Journal, etc. are dismantling that taboo cloud that hangs over the subject of sexual assault and rape—something that happens to too many women, girls, and members of the LGBTQ community. I don’t know what my poems will do in regards to changing rape culture, but I know that writing / talking about it is the only way to show the world that it is an unacceptable violence that occurs all too often in our society.

A metaphor or simile for Rad?

An America’s Next Top Model contestant. She can smile with her eyes, and she’s got a snout for days. She’s got a sturdy following on Instagram of 2,200 admirers and counting. You can follow her at @radthedog to see all of her shenanigans and beauty shots.

Sandy Longhorn: Stranger Muses

Poet Sandy Longhorn on how her cats inadvertently helped her write her latest book, why caring for animals is soul-growing work, and how to be a good literary citizen.

I'm grateful for this chat with Sandy Longhorn for so many reasons. She's incredibly insightful and generous with said insight (if you get the chance, interview her at once). But so much of what she said about caring for her ill cats really resonated with me. Caring for sick animals is almost always sure to invite unwanted opinions about "quality of life," so it's a relief to hear from someone else who finds it a worthy endeavor, despite the high emotional cost.

This week, we talk about how Sandy's cats inadvertently helped her write her latest book, why caring for animals is soul-growing work, and how to be a good literary citizen.

But first, meet Sandy: she's the 2016 Porter Fund Literary Prize winner and the author of The Alchemy of My Mortal Form, winner of the 2014 Louise Bogan Award from Trio House Press, The Girlhood Book of Prairie Myths, winner of the 2013 Jacar Press Full-Length Poetry Book Contest and Blood Almanac, winner of the 2005 Anhinga Prize for Poetry. New poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Cincinnati Review, diode, Hayden's Ferry Review, Hotel Amerika, The Southeast Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere.

Sandy holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in poetry from the University of Arkansas and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from the College of St. Benedict. She teaches for the Arkansas Writers MFA Program at the University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR, where she directs the C.D. Wright Women Writers Conference. In addition, she blogs at Myself the only Kangaroo among the Beauty, accompanied by her cat George.

When we first started chatting about this interview, you wrote, “My spouse and I have loved and lost three cats in our 10 years of marriage, with George still with us, who we adopted with Gracie, after the loss of Libby and Lou-Lou, each to unpreventable (and in one case bizarrely rare) diseases.”

Has losing so many companions in such a short amount of time affected how you think about or interact with your last living cat George?

With Libby and Lou-Lou, their deaths happened within months of each other, and we spent those months after Libby’s death in and out of the vet’s office trying to keep Lou-Lou alive. We were in crisis mode the entire time. Things are different now.

George is an older cat who suffers from hypothyroidism and kidney disease, but in the wake of Gracie’s death, we are only in maintenance mode and living a fairly normal life. Still, that fear hovers over us all the time. From George’s point of view, now that he is an “only” cat, he is loving all of the attention.

A few months ago, you lost your cat Gracie, and I know that was exceptionally hard for you. Has writing played a role in coping with the loss?

Writing does play a role in my coping with loss; however, not in the most direct way. Aside from a blog post, a few emails, or a Facebook update, I haven’t written directly about any of the cats or their deaths. However, that mourning pops up in my poems in other ways and adds a layer of gravitas to the work.

True or false: poetry is a form of coping.

Truth. Poetry helps me cope when writing it, sure, because I’m working through issues and emotions even when I’m not writing directly about a loss. However, for me, the real coping happens by reading the poetry of others. I was drawn to poetry first as a reader because a poem has the power to make such a quick connection with the audience and to leave memorable lines as touchstones.

"The real coping happens by reading the poetry of others."

Lou-Lou

You mentioned your third book The Alchemy of My Mortal Form (what a great title, by the way) was in part inspired by your cat Lou-Lou's rare blood marrow disease. Can you elaborate?

Thanks for the compliment on the title. This book is a collection of poems all in the voice of a single persona, a woman suffering from a difficult to diagnose illness. Her situation is complicated by the fact that she is hospitalized and completely alone. She has no visitors and only communicates with one other person through letters that may or may not ever get mailed.

I wrote the first poems right after Lou-Lou’s diagnosis and wrote much of the collection just after her death. Lou-Lou was diagnosed with “a fever of unknown origin.” When antibiotics didn’t clear it up, blood tests revealed shredded red blood cells. Working with a specialist, we eventually received a diagnosis of myelofibrosis: an immune-mediated disease causing her immune system to attack her bone marrow and make it fibrous as layers of scar tissue built up. She put up a good fight with steroids and immune system-suppressant drugs, but she died about four months after we learned the source of the fevers.

What’s odd is that the book revolves around a human being, and there isn’t a single cat in it. The drafts occurred organically, and it never crossed my mind to write about my own feelings of caring for and then losing Lou-Lou. As the poems in the book unfolded, two things were happening. One was Lou-Lou’s medical treatment by our awesome team of vets; the other was my father’s medical treatment by a host of doctors and nurses for both Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s. Fortunately, my father is still with us.

"Writing the book gave me some sense of control over a situation that is always out of our control in real life."

As we worked with our vets, Chuck and I were constantly awed by their willingness to go above and beyond for our cats. Often, one of the vets would call us at 7:30 p.m. (closing time is 6:00 p.m.), still at the office, still researching treatments or just providing some feedback and comfort. These people were proactive in giving our cats the best quality of life while also fighting for that life, and when the time came to make hard decisions, our vets were compassionate and honest.

On the other hand, even today, while a few stand out as exceptional, most of my father’s doctors might not remember his name, often have schedules so full that he gets only a few minutes with them at each visit, and my mother has to raise hell to be an advocate on his behalf. It was an amazing juxtaposition, and the book turned into an indictment of what I call the “medical-industrial complex,” as the sickly speaker has to navigate her treatment, in this case, all alone without any advocacy.

The last thing I’ll say is that while Lou-Lou’s death was a fact by the time I wrote the second half of the book, I myself didn’t know if the speaker was going to live or die until I wrote the last poems. Looking back, I can see that writing the book gave me some sense of control over a situation that is always out of our control in real life.

I love that you said part of being a caregiver is “embracing empathy and sadness at the same time.” If you don’t embrace the empathy and sadness, you’re swimming upstream, right? You’d have to deal with these overwhelming feelings all while trying to take care of someone you love.

While I admit that sinking too far into the sadness of a loved one (animal or human) with a terminal diagnosis can be harmful, I believe we lean too far in the opposite direction. We are conditioned, especially in the US, to deny sadness and whitewash our mourning. For me, allowing myself to be sad throughout all three cats’ last days helped me survive their deaths.

I do believe that Libby, Lou-Lou, and Gracie have all taught me important empathetic lessons about being a caregiver and mourning a loved one. I don’t think this means I’ll weather another loss any easier, but I’ll be less confused, more caring, and more willing to give myself a break when I need one.

"We are conditioned, especially in the US, to deny sadness and whitewash our mourning."

Libby

Are there specific poems you turn to when you seek out comfort?

Mary Oliver’s “In Blackwater Woods”

Lucille Clifton’s “won’t you celebrate with me”

Stephen Dobyn’s “How to Like It”

Emily Dickinson’s “After great pain, a formal feeling comes”

Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art”

Let’s switch gears a little. In your blog post “The Work Behind the Reward,” you write, “I've made a conscious effort to champion writers I admire, whether I know them or not. I've made a conscious effort to read widely and diversely to combat the gatekeepers. When I read a poem that blows me away, I Tweet/Facebook post about it. Often, I send private messages to a poet when I've read something that strikes me as extraordinary. Most importantly, I buy books of poetry, so many books of poetry that I don't have time to read them all.”

To me, these are the hallmarks of good literary citizenship, something I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. What other advice do you have for poets who want to support the community and make it more inclusive?

Seek out writers of work different from your own and interact with them and their work. We are living in a time of amazing access to all manner of voices. Take advantage of all that the online world has to offer (but don’t get sucked down the time-waste drain – some self-control is required).

Writing is hard, and many writers are more inclined to introversion, so going out and seeking literary events and other writers can be tough from the beginning. Once we find our crowd, I think we are in danger of inertia. This is not to discount the support of a solid literary community, but one runs the risk of stagnating and writing the same poem over and over again. Along with this, I think the poetry world, in particular, is prone to cliques and those cliques can lead to a kind of us-versus-them mentality. Before we can change this tendency, we have to be aware of it in ourselves.

All art is subjective, and I’m not saying we have to force ourselves to enjoy art that isn’t to our taste; however, if we don’t read widely, how will we know what our tastes are?

"If we don’t read widely, how will we know what our tastes are?"

Gracie

On your blog, you often write about the process of drafting your poems. Does blogging about the process help you revise the poems or write poems in general? Also, please tell us the secret to diligent blogging.

Hah! Your last statement makes me laugh. Once upon a time, I was quite diligent. In fact, you can find draft notes on the blog for all of the poems in The Alchemy of My Mortal Form and many of the poems in my second book. However, I’ve fallen out of that practice. In part, this is because I recently started a tenure-track job with more responsibilities than I had in my previous position at a community college. Like all things, blogging well takes time and concentration, two things I’ve been short on lately.

That being said, posting draft notes was once a great motivator to keep my BIC (Butt in Chair) and to keep me writing new poems. I confess that just a few comments on a blog post is enough gratification to make me want to post the next set of notes, propelling me to write the next new draft.

What projects are you working on now? I noticed a few blog posts about a “self ekphrasis” project based on your collages… tell me more!

When I’m not working on poems, I often work in collage. Last year, I starting thinking about a project where I would make a certain number of collages and then write poems in conversation with them. Once the project became a reality, I called this “self ekphrasis” since I was working with my own art, and the collages always came first.

One of my goals with this project was to try and explore my subconscious in a new way to find out if I had other obsessions lurking there. I tried my best to let the images of the collages guide the process. With the collages in hand, I sat down to draft the poems. After several false starts and a few weeks of frustration, everything clicked and I was able to draft a matching poem for each collage.

The result is “20 x 20: a Self-Ekphrastic Poetry Project,” which includes 20 collages and the 20 self-ekphrastic poems. I’ll spend the next few month revising the poems and sending out poem/collage pairs for publication. The ultimate goal is to publish a collection of the complete project.

Working my way back to George – do you think he’ll show up in a poem one of these days? And a follow-up: when are animals mostly likely to appear in your poems?

This is a great question. None of the cats have ever been mentioned in a poem, I don’t think. So, there’s a good chance this will remain true for George as well. Although, maybe this will be a new draft challenge. I admit that I might have steered away from poems about Chuck and the cats, or from even including them tangentially, because of the way these subjects often result in women’s poetry being labeled “domestic” as a way of lessening its importance.

I’m also fascinated with the next question. The animals most likely to show up in my poems are non-pets: coyotes, fox, bobcat, birds of all kinds, wolves, bears – they’ve all been there. I’ll be thinking about why this might be the case and what I’m trying to say by featuring the wild over the tamed.

"These subjects often result in women’s poetry being labeled 'domestic' as a way of lessening its importance."

Lou-Lou & Libby

A simile or metaphor for your cats?

George has a voice like a firehouse alarm when he is hungry or lonely, but he is my mindfulness guide, reminding me to stay in the moment.

Gracie was a green-eyed bowling ball of a diva; she was the only cat that never lost weight on chemotherapy.

Lou-Lou was Tony Hawk’s shadow; she could leap and zoom with the best of them.

Libby was my blood pressure medicine, hot water bottle, and bed burrower.

Emilia Phillips: A Lesson in Joy

Emilia Phillips discusses the wordless bond between her and her dog Grady, the humanness of dogs, and how to find an occasion of joy.

I've had dog joy on the brain lately, and I can't properly introduce this interview with poetry hero Emilia Phillips without noting her thoughts on it came at the right time. As I try to figure out what to do for my terminally ill dog Pete, Emilia's words are both a salve and a reminder: yes, our dogs pass through our lives too quickly, but they can teach you joy. And it can alter your life.

For me, joy is such an elusive thing. I joke sometimes that my neutral is melancholy. But the magic of dogs is that they pull you out of your head and on to their level. If you pay enough attention, you'll find what Emilia calls "ideas for occasions of joy." (Spoiler: everything she says is thoughtful. That's just how Emilia operates.)

So let's bask in Emilia's insight on the wordless bond between her and her dog Grady, how his companionship prompts her to practice empathy, the humanness of dogs, and how to find an occasion of joy.

If you haven't been fervently following Emilia's work (um, get on that), here's a little background: she is the author of two poetry collections from the University of Akron Press, Signaletics (2013) and Groundspeed (2016), and three chapbooks, most recently Beneath the Ice Fish Like Souls Look Alike (Bull City Press, 2015). Her poems and lyric essays appear in Agni, Boston Review, Gulf Coast, The Kenyon Review, New England Review, Ninth Letter, Ploughshares, Poem-a-Day, Poetry, Verse Daily, and elsewhere. She received StoryQuarterly’s 2015 Nonfiction Prize, The Journal’s 2012 Poetry Prize, as well as the 2013–2014 Emerging Writer Lectureship from Gettysburg College and fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, The Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop, U.S. Poets in Mexico, and Vermont Studio Center. She is the Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Centenary University. She’s now at work on new poems, a collection of lyric essays titled Wound Revisions, and Offset: A Poetry Broadside Digitization Project.

You noted you adopted Grady in 2015, and “he was born the same week in early January of that year that we had to put down my husband’s 15-year dog companion Phaeton.” I love that you noted that connection – did it affirm you and your husband made the right choice?

Phaeton died the week of her birthday. We didn’t intend on getting another dog right away, but our other dog at the time, Percy, was beside himself with grief, and so our vet suggested that we get a puppy to accompany him. By the time we started looking for another dog, Grady was put up for adoption through a rescue group. We were already in love with Grady; he was goofy and shy and sweet. Then they said when he was born, and we knew he was right.

You mentioned in our pre-interview chat that you don’t write much about Grady because “animals in past poems haven’t had the best fates.” Is this a similar notion to getting a tattoo of a lover’s name? That permanence – in poem or ink – invites doom?

This may be a chicken and egg sort of thing. I’m not sure if poems themselves invite doom so much as doom invites poems. Because of my happiness in having a pet, I haven’t felt the need to write about having a pet. I admit: I don’t know how to make it interesting without loss. Maybe that’s something I need to continue working on.

"I’m not sure if poems themselves invite doom so much as doom invites poems."

I lean hard on my dogs for comfort. Has that been true for you? Can you talk a little about how profound that comfort can be when words fail?

I certainly do. This summer, I have spent a great deal of time at home, and in a small town where I know no one else. Without Grady, I feel I would have gone crazy in my head. Additionally, he may not be able to speak words, but he’s the most talkative dog I know—he seems to want to speak. He vocalizes his wants. In some strange way, he makes an argument for the strength of a voice, even when words themselves fail.

I recently read and loved your chapbook Bestiary of Gall (Sundress Publications, 2013), a collection of fables (many about animals) reimagined and recast in the contemporary, human mode. This is a world where the real – foxes and drones and carrier pigeons with incendiaries and war – feels surreal in its retelling. What was the impetus for this collection, and why are animals a natural vehicle for the violence, chaos, and majesty of this subject matter and experimental form?

Sometimes I think the one-to-one equation between the realm of beasts and violence simplifies animals to their instincts. In this chapbook, I wanted to reckon with the notion that human violence demonstrates our species’ “animal” side; ultimately, I felt that wasn’t the case. I think animals of all kinds have lives and personalities beyond their instincts, and their instincts—even for violence—are natural. Human violence, I believe, is much more sinister than animal violence, but who’s to really say? We can never truly know what it’s like to be an animal, what an animal sees.

"We can never truly know what it’s like to be an animal, what an animal sees."

You described “Pastoral (With One’s Head Out the Car Window)” as a poem that exhibits “the same kind of dog-joy of putting one's head out the window of a moving car.” A sample:

Although drizzle nettles the cheeks red

& one’s ears fill with wind’s grey-green noise—

there’s clover & honeysuckle, the cheeks held

intimately by almost nothing.

Let’s talk a little about the importance of acknowledging joy with poems (it’s harder than it seems, right?). Does Grady help you in this regard?

It’s so hard to acknowledge joy in poems, and I’m so glad you saw this moment as joy. Grady—well, really, all the dogs I’ve ever had—give me ideas for occasions of joy. They lead by example. When I was a kid, I started riding with my head out the window because I saw my dogs do it, and I still do it occasionally because it feels so amazing. It allows for a moment in which all my human responsibilities blow away in the window, and my ears are filled with white noise, and I can just be in my body. Sometimes Grady just reminds me the joy of being in a body, to being a thing: to do, to run.

This summer I have been taking Grady on long walks to an abandoned suburban tract. The lots without houses have grown up with shrubbery, and deer live there. I have spent some of the best moments of my entire summer standing with my dog at the edge of a tall thicket listening for something inside. Often we see deer, and there are orioles and blue birds that swoop over our heads. Sometimes we even venture back into the thickets, in a kind of young flowering grove. There, I am beyond myself, entirely focused on having a similar experience as he does. In some ways, I would say, having a dog makes me more adept at understanding the experience of another because Grady’s experience of the world is often so different than mine that when I try to imagine what his experience is, it closes the gap between my experience and those experiences of other people that are more like mine than his.

"All the dogs I’ve ever had give me ideas for occasions of joy."

You mentioned that Groundspeed’s poem “YouTube: Dog Eating a Human Leg on the Ganges” demonstrates “the way in which I embrace the animalness of a pet even as I talk and sing to my dog, personify him by lending him human emotion, and so on.” I think dogs are such an interesting case study for this – they are perhaps the most humanlike animal we interact with on a regular basis, and maybe that humanness is directly derived from the fact that they could turn on us, and we simply have to trust that they won’t.

Do you think it’s this dynamic that makes dogs a ripe subject matter for poetry?

Our last dog, Percy, had been severely abused and abandoned when he was an adolescent. The humane society found him chained up behind an abandoned house in Newport News with a chain growing into his neck. He was always a nervous dog, a little unpredictable, but when Phaeton died, he became so struck with grief that he was self-harming when he was left alone during the day. He began to chew his legs and paws until they were bleeding; he threw himself against the crate and walls. After Phaeton’s death, he suddenly became dog aggressive. One day, while a dog sitter was walking him, he got away from her and attacked a neighbor’s foster dog, and we had to pay for the surgery. Fortunately, Percy had broken a couple of his teeth earlier in his life and didn’t do that much damage.

I took Percy into the vet, and they did behavioral assessments and put him on Prozac. As I mentioned before, the vet suggested that we get a puppy (Grady) to give him companionship. They felt that he would have the drive to take care of and bond with a puppy, and he did—until Grady became a full-grown dog. One Sunday, I was working in the kitchen and, without prompting, Percy ran in from the other room and attacked Grady. I couldn’t get him off of Grady, even though he didn’t even break the skin. I don’t know how long it was, but I finally got them away from one another and I dragged Percy to his crate. His eyes were like nothing I’d ever seen. He didn’t even look like himself; it was like he was possessed. After about fifteen minutes, his eyes softened and he began to whine. It was the saddest thing I’d ever seen. He was a liability, I knew, and I didn’t want Grady in danger. He never once acted aggressive toward a person, and even in that fight, he was gentle toward me. Still, I was suddenly afraid of him. That’s when I knew we had to put him down, and the vet agreed. I sobbed the whole time. He licked the tears from my chin as they injected him. He was eleven.

For me, seeing that side of a dog come out was terrifying. It was like I’d been on the main line into Percy’s wildness. Of course, that line was opened by human abuse and trauma, something that never left him. The vet described it as PTSD, which had once again been triggered by the death of his companion. Once I heard that, it made me feel that, no, it wasn’t the animal I was seeing in him. I was seeing something essentially human, or what we know to be a human experience. That violence wasn’t animal; it was human.

The humanness I see in Grady is altogether different. It’s non-violent. It’s talk, albeit wordless. It’s also his personality, his attention to emotion. So, I would say that the humanness of dogs is what attracts us to them, whether or not that humanness is good or bad.

"The humanness of dogs is what attracts us to them, whether or not that humanness is good or bad."

Shifting gears a little: for three years, you interviewed poets for the 32 Poems blog. What did being on the other side of the interviewing process teach you about engaging with other artists? Asking for a friend.

One of the best takeaways I had from interviews is that the conversation often gives both the interviewer and the interviewee insights into the work at hand. When I’ve been interviewed, I often feel like I find out something about my work I didn’t know, and I had more than one interviewee express the same. The conversation and its capacity for mutual discovery helps fortify the notion that the poems have their own lives.

You recently completed your third manuscript Empty Clip (congratulations!!). What’s next for you? Can I expect more animal poems?

Thank you so much! I am working on some new poems for a possible new project, some of them really come out of the time I’ve spent without words in my summer with Grady. He’s already in some of the poems.

A simile for Grady?

Like a younger prince who never has to be king, he doesn’t care who’s watching.

Ruth Baumann: Feral Like Me

Ruth Baumann talks about the heart-opening work of caring for animals, how her two adopted cats helped her get some stability in her life, and her best advice on getting your poetry to stand out in the slush pile.

Ruth and I are working on a little theory: maybe all Ruths are ardent animal lovers. (Are you a Ruth and a detractor? Let us know so we can account for outliers.) Maybe one day we'll meet in person and it will be an instant Disney movie – animals EVERYWHERE. #TeamRuth

Here's the next best thing: talking to Ruth about the heart-opening work of caring for animals, how her two adopted cats helped her get some stability in her life, the feral nature of love and heartbreak, and her best advice on getting your poetry to stand out in the slush pile.

So now that you're biting at the bit to hear her do the talking, some background: Ruth Baumann is the author of three chapbooks: I’ll Love You Forever & Other Temporary Valentines (Salt Hill, 2015), wildcold (Slash Pines Press, 2016), and Retribution Binary (Black Lawrence Press, forthcoming 2017). Her poems have been published in Colorado Review, Sonora Review, Sycamore Review, The Journal, Third Coast, and others. She received an AWP Intro Journals Project Award in 2014. She holds an MFA from the University of Memphis and is pursuing her PhD at Florida State University.

Additionally, she is former managing editor of The Pinch literary journal, and she currently edits Nightjar Review with Tara Mae Mulroy. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with her two cats Julia and Autumn (and the occasional foster feline).

You mentioned that you adopted your cats Julia and Autumn from the Richmond SPCA when you were in a transitional period in your life. Was it the uncertainty of this time that made you seek out your cat companions?

I wonder about this—or, the bigger picture version: what draws me to animals, particularly cats? I’ve always loved animals, always gravitated towards that which watches, communicates differently, needs protection or translation. There’s something really comforting to me about the animal mind, about how wild & honest it is. I think it’s a sort of perpetual underdog empathy that comes from a billion sources & can be analyzed to death but never eradicated.

On a smaller scale: I was something of a delinquent youth (as I imagine many artists were), & I adopted the cats a little over 8 years ago, when I began to transition my life into stability. I think the turn into acceptance of a normal, non-chaotic life allowed me to open my heart back up, & to be able to care responsibly for animals. Anytime I’m not in fight-or-flight mode, I feel like the person I want to be, which is one that is useful & has a lot of love to give. The cats probably grounded me in this new life as much as I helped ground them in a home where they’d be loved (the little one, Julia, was an owner surrender multiple times before we fell in love, & I believe she’d been abused).

Also, I grew up with cats, & have consistently loved them—I’m the weirdo at the party who will go hang out in the corner with the resident cats rather than talk to y’all.

"There’s something really comforting to me about the animal mind, about how wild & honest it is."

Autumn

I love the biographical note left in Julia’s file when you first got her: “EVIL.” They didn’t even try to mince words, huh? Can you talk a little about how affirming the affection of a picky animal is? And what caring for animals teaches you about unconditional love?

Oh, so affirming! I’ve given it a lot of thought & Julia is pretty solidly my soulmate. (Or, one of—I guess we get a few.) Like I mentioned, I got them when I was in the process of shifting lifestyles, & any transition that requires letting down defenses & feeling what’s been numbed causes a lot of fragility. Fragility that’s been there all along, I believe, but has been masked. Julia in so many ways represents this me, the me that I still contain: she’s been endlessly loving to me from the first moment (she will sit by me sometimes & purr for hours on end, she is waiting at the front door whenever I come home—even if it’s just from a walk to the mailbox, etc.), but gets so instinctual sometimes. If someone pets her too soon, or if I pet her too much, or don’t pay attention to her body language, blood is shed (very literally). I had an ex she used to spit on—I’d never seen a cat spit before!

I believe that most creatures are like that, honestly: it’s just our hurts that block our unconditional love capacity. By whatever stroke of luck/fate, Julia recognized a kindred in me, & we bring out the best in each other. She’s mellowed a little bit over the years, too, believe it or not. (Autumn, too, is a fragile spirit—she was found on the streets at about a year old, & is incredibly skittish. Once she’s comfortable around you, she’s completely demanding of love & won’t stop purring & cuddling, but until then, she will—despite being a 17 pound calico—be impossible to find.)

I think unconditional love is easily taught by animals. I think perhaps more correctly, unconditional love is already inherent but animals remind us of it. There’s no fear of the hurt or trickery that can come from human relationships, really—a kitten won’t have control issues or manipulate you or drink too much or fall in love with a different person, etc. (I hope.) Taking care of animals also grants me a specific purpose in the relationship—especially in the case of the baby kitten I fostered recently & had to bottle-feed every few hours—which I think is a lot of what we want as humans, to feel love (not just towards us, but to feel love outwards) & to feel useful. I’ve heard a lot over the years about love being not a feeling but an action, & taking care of animals is a great way for me to practice this.

"Unconditional love is already inherent but animals remind us of it."

Ruth and Julia

To thread the needle of the last question, let’s talk about your poetry through the lens of unconditional love. Does it play a role in your work or how you engage with your subject matter?

That’s an interesting question. I wish I could say yes, but so many of my poems have come from my wounded places, from my difficulties with trauma & human relationships & reconciliation with my past that I’m not sure they deal in unconditional love as much. They try to. They try to wade through the conditions they were taught, & they try to learn to love themselves & others as best they can. I guess my poems are as fallible as their writer. While there are moments of light in the poems, they’re often more concerned with seeking & broadcasting the truth than a particular kindness or love.

Poetry is often a safe space for me, as all written language is, to work out the pains that can’t be expressed healthily or comprehended in a particular relationship (often the relationship between self & universe). Maybe I can reframe this as unconditional love for self being an unspoken tenet of writing at all—that there’s some hope, some flicker of survival that wants to be love underneath every attempt at communication, growth. Otherwise, why bother?

Even in your poems, the speaker can’t stop thinking about the wellbeing of the animals that populate the lines. Examples: in “Loving You Terrifies Me,” you write: “Your fear is waking up with a raccoon in your face. My fear is / the poor animal will realize there’s another side” and in “In Media Res,” you write: “Scientists are killing one species of owl to allow another to survive. / I’ve forgotten to read the news for a decade. Promise love isn’t a series of / selfish confessions? Did anybody ask the owls?” Would you say that’s a confessional impulse at work?

Oh, of course! Probably all writing (& all actions) are confessional, really. Also, I literally was dating someone once that had a wild animal in his attic. Every night we’d go to bed this one winter & hear scratching above our heads. This was years before I fell in love with raccoons, of course, so I didn’t befriend him/her. That anecdote isn’t really that useful, but it’s confessional, too.

I don’t know anything beyond my own experience, I think. I mean: I can understand many other things, I am guilty of having way too many opinions sometimes, I can sympathize & empathize with others, etc.—but all that I can truly speak to is that which I have been through. I try to be mindful of never speaking for that which I’m not qualified, & I’m sure this reflects in my poems.

"I identify with the sense of watchfulness, the wariness of animals."

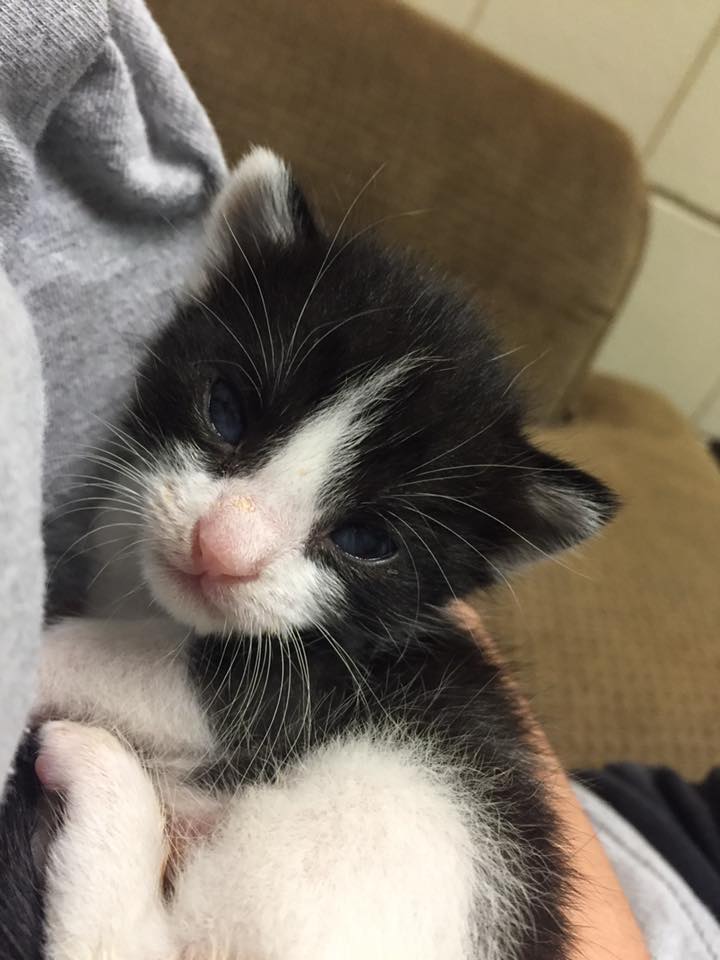

Ruth bottle-feeding Luz

I was so heartbroken to hear your little foster kitten Luz didn’t survive, but I’m moved by how deeply you cared for her in your short time together. Can we expect to see a poem about Luz in the future?

Yes. I’ve already written her into some. I also dedicated my full-length manuscript to her. Luz meant a lot to me because she was ridiculously perfect, & I’ve never been in that much of a mothering position before: it’s impossible (at least for someone like me) to not attach deeply to an animal you wrap up in a washcloth & bottle feed & tuck in with a heated blanket every few hours. (I mean—did you see the pictures?) I also was going through a period of some loss in my personal relationships, & having an animal to love deeply & claim as family was really crucial to my healing at the time, to my remembering & walking back into the depths of my capacity to love.

Animals show up quite a bit in your work, especially when you write about love and heartbreak. How are these ideas linked for you?

We are animals! I think humans forget that far too often. We are animals, pack animals at that. As much as it may seem that our consciousness separates us, & our laws & rules & ideologies do, I don’t think we’re that far off from the other species. We are just one animal on the planet, & it gives me peace to remember this. Also, as a writer, as a Pisces, as an introvert, etc., I identify with the sense of watchfulness, the wariness of animals.

In terms of love & heartbreak, I believe these are some of the most deep, visceral emotions we can experience, & I’ve often felt intensity that seems wild. If you’re a poet & you don’t claim you’ve felt feral before, I’m not sure I believe you.

"If you’re a poet & you don’t claim you’ve felt feral before, I’m not sure I believe you."

Autumn

You’re the author of three chapbooks: I’ll Love You Forever & Other Temporary Valentines, wildcold, and Retribution Binary. What about the shorter form of the chapbook appeals to you? And your best tip for putting together a chapbook?

I think maybe my attention span? It’s easier for me to write a cohesive body of work when it’s shorter. I’ve actually written some longer manuscripts, but they usually eventually end up feeling too disparate—it’s really difficult to pull together a full-length book’s worth of poetry that connects from the first to last page.

The best tip I have for putting together a chapbook is to print out everything you’ve written lately (lately being a relative term) & spread it across your floor. Then I pile together the poems that make sense with each other, the poems that speak to each other, & see if the pile(s) are big enough to attempt a larger endeavor like a chapbook or book. Usually, poets have obsessions or work through something for long enough that there’s a thread through a season’s worth of work, I think.

Fill in the blank: when you’re reading through piles of slush, the work that most catches your attention…

Has a moment of truth. Has a break into clarity. Says beautiful things that have meaning, gives as much credence to the message as to the delivery. Reminds me of an old self or a new way to look at my current self or a self I want to be.

"My cats are like an affirmation from the universe."

Meta Julia

If cats were a poetic form (e.g., sestina, sonnet, ode), they’d be…?

Free verse! Would you try to contain them?!

A simile for your cats?

This stumps me. I want them to be metaphors. My cats are like an affirmation from the universe.

Sonya Vatomsky: Hierarchify Your Love

Poet Sonya Vatomky talks about how their companion Magpie Underfoot helps them write and survive.

It's hard not to fangirl over Sonya Vatomsky, gothy, cat-loving, say-anything poet with a must-follow Instagram feed and a penchant for concision. So I will cosign myself to saying this: I could've probably asked Sonya any boring question and their response would've been interesting. That's just who they are.

But fear not, dear reader – I didn't put that theory to the test. I talked to Sonya about their painfully cute companion Magpie Underfoot and how this cat helps Sonya write and survive.

A little about Sonya before we hop to it: they are a Russian American non-binary artist with too many feelings on the inside and too much cat hair on the outside. They are the author of Salt Is For Curing (Sator Press, 2015), a debut poetry collection about bones, dill, and survival, as well as one chapbook. Poems, essays, and interviews have appeared in Dirge Magazine, Entropy Magazine, The Hairpin, Lodown Magazine, VIDA, The Poetry Foundation, and other publications. They live in Seattle with their cat, Magpie Underfoot, and a growing collection of taxidermy, wet specimens, and other oddities.

[CW: sexual assault]

Your cat has the coolest name. What inspired it?

Thank you! She’s named after the recurring symbolism of the magpie in 80s progressive rock band Marillion’s lyrics. “Underfoot” was added later after our vet called her “Magpie Vatomsky” — she doesn’t strike me as the kind of cat who would take someone else’s last name.

You mention that you adopted Magpie Underfoot from the shelter and she was "horrifically underweight." Can you talk about the process of caring for her in those early months and what impact it had on your relationship with her?

She fattened back up to normal quickly so that wasn’t really an issue, but whatever her life was like before the shelter left its mark. The first six months I had her, she’d meow me awake at 4 a.m. and meow the entire time I was at work. I almost had to move! She still gets really pissy when she can see the bottom of her food bowl; she has a little plastic bow she carries around and places in her food dish when she’s dissatisfied with it. It’s from a Christmas like 3 years ago but is so funny I don’t throw it out.

“She doesn’t strike me as the kind of cat who would take someone else’s last name.”

In our pre-interview chat, you said Magpie Underfoot is "more like an emotional support source without which most of my writing wouldn't happen." That made me remember your interview with Maudlin House when you said Salt Is for Curing is about "exorcising my demons – literal demons, literal exorcisms." I'm thinking there's a connective thread here – did Magpie Underfoot's emotional support help make those exorcisms possible?

Yes, absolutely. Around when the catalyst for my book happened — actually, I’m just going to be blunt here. I got assaulted by a friend of a friend after a party, and in the month or so around that, I also started taking antidepressants, had a horrific breakup, and needed a medical procedure that really stressed me out so I was basically a shitshow. Magpie, who normally slept by my feet, started sleeping on the pillow next to me. She still does that. I put both arms around her and my nose in her fur.

You described what I'm going to call "love transference" in your poetry, where you're writing about one subject, but channeling feelings you have for another. And I love how you put this to use in "Valerian Tea," a poem you said is "some kind of weirdo hybrid love poem about her [Magpie Underfoot] and my partner." (For our readers, a taste: "this interconnected belonging where our / eyelashes braid together and I fossilize with you and die / tomorrow and live forever and my face feels like my face…") How has Magpie complicated your understanding of what love is?

I don’t think she’s complicated it. Every once in a while my brain does the thing where I NEED TO HIERARCHIFY ALL MY LOVES and I’m like, is it reasonable for a cat to be this important? But she is, so whatever.

“Every once in a while my brain does the thing where I NEED TO HIERARCHIFY ALL MY LOVES and I’m like, is it reasonable for a cat to be this important? But she is, so whatever.”

Not a question about animals, but a question about being a human animal. How has identifying as non-binary influenced your work? I'm thinking specifically about Salt's meditations on what it means to occupy space in a patriarchal world.

At the time that I was writing Salt, I felt very female. It’s actually the only time in my life I’ve felt that way and it was in the aftermath of a sexual assault — like a man stamped WOMAN on my brow. To be so viscerally read as a woman after a lifetime of feeling inadequate was a bit of a journey, for sure. I started coming out as non-binary around when Salt got the publication offer and was worried that would be weird somehow, but it hasn’t been.

Tell me about your writing process. Do you have a ritual or schedule you follow? Does the poem start with an idea or a line? Is Magpie nearby?

No ritual or schedule, but I do prefer to write at home and my apartment is tiny so she’s definitely nearby and trying to sit on my laptop.

“To be so viscerally read as a woman after a lifetime of feeling inadequate was a bit of a journey, for sure.”

Salt is full of references to the body – specifically, the human and animal body as meat, fitting for a collection that uses food as a device to explore power dynamics and to dissect the self. But I want to focus on a specific animal – the fish in "Spidersilk" ("You looked so far away, I felt crazed; gutted myself like / a fish and dug in") and in "Herring under a fur coat" ("I put my coat on. Under, I / am cold wet fish, scales and weights, / I am wide maw and narrow fin"). Why did you choose the fish to name the vulnerability in these poems?

This isn’t that philosophical, but a fish is basically the only animal your average home cook is going to gut, yeah? I wanted the gutting to feel messy and vulnerable but not add any extra context, like using a deer or a rabbit might have. “Herring under a fur coat” is actually just the translated name of a Russian salad, which is why that poem also has all those beet and potato and mayonnaise bits.

True or false: poetry is a kind of spell work.

Definitely.

A poem with an animal in it (metaphorical or otherwise) that you wish you'd written?

I’ve been writing a lot about whales recently, even though I kind of dodged that fish question up above. I guess it would be another sea creature. I’m really fascinated by how little we know of the deep sea, the animals that live there.

“A fish is basically the only animal your average home cook is going to gut, yeah?”

A simile for Magpie Underfoot?

A little lemon. She is so sour. I love it.

Amie Whittemore: The End of an Era