Megan Peak: Something Other than Myself

I don't know about you, but I've been keeping my eye on Megan Peak, a hella smart writer who is already penning some of the most memorable poems I've had the good fortune to read. She's bound to do amazing things over her career.

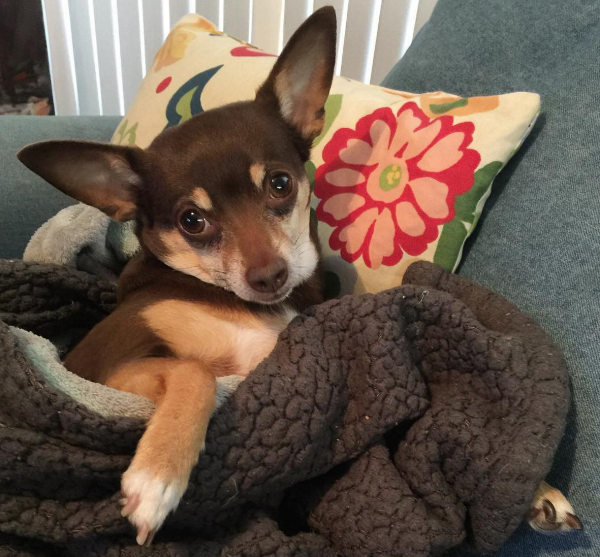

And so as a Halloween treat (no tricks), you get to spend some time with Megan and her dog Radish. We chat about how Rad helps her put self care first (and how writing is part of that process). We also discuss bridging the gap from poetry thesis to book manuscript and poetry's role in effecting social change, including dismantling rape culture.

I told you – all treats.

A little about Megan: she received her MFA in poetry from The Ohio State University, where she was former poetry editor at The Journal. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming from Blackbird, DIAGRAM, Four Way Review, Indiana Review, Muzzle, Ninth Letter, North American Review, PANK, The Pinch, Ploughshares, Sou'wester, Tupelo Quarterly, and Valparaiso Poetry Review, among others. She lives in Fort Worth, TX with her partner and her dog Radish. You can find her at www.meganpeak.com.

Tell us a little about Radish and how she came into your life.

My family has always had pets. There hasn’t been a time in my life when I didn’t have an animal of some kind as a part of my daily experiences. So, when I moved to Ohio from Texas for my MFA, I felt that void intensely. And, if I remember correctly, the five of us poets in the incoming MFA program were some of the most heartsick people—all coming from some personal grief: break-ups, homesickness, sheer loneliness. But, as the year went on, I was comforted and enlivened by my cohort, my professors, the act of coming to the page day after day, the poems. So, when I rescued Radish in my second year at OSU and she was the one mistreated, malnourished, fearful, I was ready to tend to something other than myself. She taught me a great deal about relearning how to trust and practicing patience.

From what I can tell, Rad is part Chihuahua, part Miniature Pinscher. The people at the shelter named her Radish, and I couldn’t agree more with the name. She has a little kick to her—bold but sweet. She’s fiercely loyal, smart, and resilient. I think she misses the snow and the longevity of the Ohio winter, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter because she is such a mama’s girl. She is happy wherever I am. She is sitting on my lap right now, belly thick and rhythmic with whatever little dream she is having.

"I was ready to tend to something other than myself."

Throughout these interviews, I’ve talked on and off about my experiences with Dog Magic. It’s difficult for me to picture how much different a person I would be now if it weren’t for my dogs. (For example, my dog Pete is the reason I became a vegan. She’s also the reason I’m a very reluctant traveler. She hates traveling.) Have you noticed any significant way your life has changed because of Radish’s companionship? Has she impacted your writing?

I think, with Rad’s help and the outright passage of time, I have become more aware of my need to balance self-care with that of comforting others. What I love about Radish is that if she doesn’t want to be crammed on the couch with my partner and me while we watch a movie, she will jump down and curl up in her bed. I love that independent impulse in her, knowing when she needs us and when she would like to have some space. There have been times in my life when that boundary has been slippery at best, and when I notice these small moments with Radish, I find some affirmation in my impulses to be alone, to reach out, and/or to serve others.

Going off of that, one of my needs is to write. So, Radish does influence my writing, I suppose, indirectly. Writing exists, for me, as a form of self-care because without it I become anxious, overwhelmed, unable to process my surroundings and the events in my life. She aids in that ritual of returning to the page each day.

What’s one poem you couldn’t have written without a spark of inspiration from the animal world? What unexpected place did it take the poem?

Actually, my whole second manuscript that I am currently working on draws directly from the animal world. Egrets, horses, does—the project emerges from the strange connection between sisters and place and what drives one away from and back toward family. The manuscript explores the wild and the domestic, the exterior worlds of New Orleans, of swamps, of the Texas plains and the interior spaces of the home. It focuses on the female experience of marriage, of sacrifice, of daughterhood and sisterhood. The project attempts to examine that very tender, wild thread that links sisters as they bear witness to each other's trajectories. Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual.

One poem, “The Egret Bride,” which was recently published in Iron Horse Literary Review, is one such piece. It was one of those pieces that had no title, that began after reading someone else’s work (Kiki Petrosino, I think!). Ultimately, I found a way to speak about marriage, what one might lose in that union, and the ways in which family influences our choices. The poem documents the speaker watching as the sister transforms from girl to egret, from daughter to wife, from connected to estranged.

"Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual."

You graduated from OSU with an MFA in poetry last year (belated congratulations!). I don’t know if this is true for you, but I graduated expecting to just shop around my thesis as my book and that would be it. But after sitting with it for a couple months and even after getting a few finalist bites, I realized I still had more work to do before the thing was a legit manuscript for me. What has your experience been like? How much distance is there between your thesis and your current manuscript?

Oh, I definitely feel that. I knew the thesis wasn’t where I truly wanted it to be after my defense. My professor and mentor even said, “You have a thesis, but now we need it to be a manuscript.” I’m a perfectionist, so I don’t know if it will ever really be “done,” in my opinion, but the fact that I am comfortable moving on to this second project is a good sign that the manuscript is in the right place. And yes, the manuscript is pretty different than the original thesis—different title, different order, new poems, all of which has created a more compelling arc than what I originally had. Here’s to hoping that it won’t be a bridesmaid for much longer!

Your biggest, most ostentatious poetry goal that you may not even want to publicly admit? Here, I’ll share mine: I want to win a freaking Pulitzer one day.

Oh, goodness. I suppose I would love to be financially stable from my poems and books one day, to be able to rely solely on my writing as a source of income. I don’t know if that will ever happen with poetry, but one can dream. On a broader note, my partner and I are working on a graphic novel together, and I would absolutely LOVE 1) to finish it and 2) to have some network like HBO pick it up. That would be the life.

Several of your poems are about sexual assault: “Elegy with a River Inside It,” “What I Don’t Tell My Mother About Ohio,” and “When Asked If I Said ‘No’.” How do you balance the beauty of language when writing about something so violent and traumatic?

I’ve always remembered this quote by Plath from her journals:

“Some things are hard to write about. After something happens to you, you go to write it down, and either you over dramatize it, or underplay it, exaggerate the wrong parts or ignore the important ones. At any rate, you never write it quite the way you want to.”

The poems that you mention and others that address assault and sexual violence came from this very raw and unhinged place at first. Just me trying to get it down on paper. And yet, they never felt “right” or “done” or whatever you say in terms of finishing a poem. People in my workshop never really knew what to say about them, except that it was brave or important or necessary work. While it was nice to hear, it wasn’t helpful. So, I had to find my own way to frame these poems, and that usually emerged by juxtaposing the “drama” or trauma of the event with the violent beauty of place, environment, weather. I think it helped me, and I suppose the speaker of the poem, to fluctuate the lenses on these traumatic moments, which felt truthful to the experience and gave the poem / reader perspective.

"Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict."

And a headier follow-up: what role do you think poetry has in changing rape culture?

Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict. Even now, we have poets writing necessary pieces ranging from race and gun violence to the injustices of the current academic job market in regards to contingent faculty. So, I think poetry has and always will have a vital role in bringing awareness to cultural and social trends and issues.

Will my poems change rape culture? I don’t know. But magazines publishing these pieces like Vinyl, Winter Tangerine Review, Tinderbox Poetry, The Adroit Journal, etc. are dismantling that taboo cloud that hangs over the subject of sexual assault and rape—something that happens to too many women, girls, and members of the LGBTQ community. I don’t know what my poems will do in regards to changing rape culture, but I know that writing / talking about it is the only way to show the world that it is an unacceptable violence that occurs all too often in our society.

A metaphor or simile for Rad?

An America’s Next Top Model contestant. She can smile with her eyes, and she’s got a snout for days. She’s got a sturdy following on Instagram of 2,200 admirers and counting. You can follow her at @radthedog to see all of her shenanigans and beauty shots.