Gretchen Marquette: The Last Time We Were Strangers

Poet Gretchen Marquette on her life-making relationship with her dog Lucy, the creative process, Rumi's love dogs, and what animals have taught her about vulnerability.

I'll keep this short because I want you to experience Gretchen Marquette’s love stories about her dog Lucy and her insight on the creative process right now. But I will say, if you haven't checked out her first book May Day yet, do it. It sticks with you.

About Gretchen: Her work has been featured in Poetry Magazine, The Paris Review, Tin House, Harper’s, The Literary Review, PBS NewsHour, and other places. Her first book, May Day, was released in 2016 from Graywolf Press. She lives and works in Minneapolis.

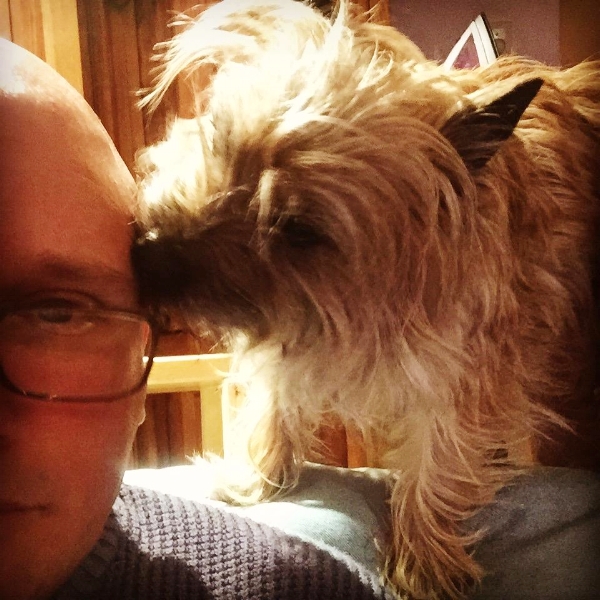

Tell us about Lucy and your 14 years of companionship with her. Some favorite moments, memories?

I brought Lucy home on Mother’s Day in 2003. Lucy (then named Minnie) had been living at a shelter for six months, and was a little over a year old. I’d gone to the Humane Society with a friend to see if they had any rabbits, but while we were there, he convinced me to look at the dogs, and the second I saw her, I knew she was mine. I visited her several times, and went through the long application process they required, but eventually I was there handing a green leash over to the woman behind the counter. She said, “This morning I told Minnie that she’s finally going to her forever home.”

Now that I’ve written that, it sounds saccharine, but it wasn’t. Lucy had shown up there in pain and a little underweight, and watched her littermate be adopted and disappear three days into her own six month stay. She arrived knowing no commands, and with an infection in her leg so bad she couldn’t step on it. She wasn’t spayed, and didn’t know her own name. I didn’t know it yet, but here was a dog that wanted to be touched all the time, and she had gone so long without any consistent affection. And all of that was over for her. She did have a home.

There have been dark times in my life, but rescuing Lucy and giving her the love she wanted is one thing I know I’ve done right, and one reason I’ve been glad I was alive to help her. We’re getting into an It’s a Wonderful Life moment here, which is the opposite of trying to prove all this isn’t saccharine, so I’m going to stop there.

When I took Lucy outside of the shelter, she was too afraid to get in the car. It turned out she was afraid of everything. While we stood there, a strong wind blew, and she cowered in the grass and peed. It had been so long since she’d been outside, and her entire puppyhood had been spent in a small outdoor kennel. I knew I had to lift her in the car, but I was afraid, too. Would she bite me? It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since.

It’s hard to pick the stories I want to tell about my life with Lucy – I could write pages and pages, and this is especially true because until July of 2014, there was another dog with us – my husky, Sage. Sage and Lucy were not very close most of the time, but were partners in crime when it came to getting in trouble – running away in particular.

Once, I got a phone call from an unknown number. It turned out that someone had left the gate open at the house I was renting, and my dogs had gotten out. Lucy is a Treeing Walker Coonhound, but when the woman said, “I have your beagle I think?” I knew it was Lucy. “My husband is trying to catch your husky,” she said. I was two hours away, so I told the woman my address and asked if she would put the dogs inside (I left my doors unlocked in those days), and she said, “Honey, these dogs have been down to the river rolling in dead carp and they are covered in it.” When I showed up at home, I saw for myself. It was the foulest thing I could imagine, but they were both so happy. Still, it was a night of a thousand baths.

Lucy has always been a good friend to me; she’s very tuned in. One night, I woke in the worst pain I had ever felt. I would have a root canal later that day, but when I woke, I didn’t know what was going on, and it was 3 a.m., and I was afraid. My boyfriend told me to relax and not get upset because it would make it worse, and then went back to sleep, but Lucy sat up with me for hours while I cried on the living room floor. At one point she came and sat right in front of me, and I put my arms around her and cried into her neck, and she sat there and let me do that for as long as I needed. It was a profound experience of being loved and comforted – it’s for that reason that of all the thousands of days I’ve spent with my dog, this is one I choose to tell you about.

"It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since."

In your book May Day’s dedication and in your interview with Kaveh Akbar on Divedapper, we can see that you value your friendships: “I don’t think I’d be here if it wasn’t for those friendships. Which is strange because we give such a privileged place for romantic love and familial love, but in both of those forms of love you are under a contract in some way. But then you have friendships, which have actually been some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had in my life.” Do you count Lucy among these life-saving relationships? Or do you consider that relationship more familial? I’m always curious about how folks think about their relationship with their pets.

My relationship with Lucy is definitely a life-making/life-saving one. She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman. I realized recently that I’ve spent more time with her than I have with my siblings.

One thing I hate is getting in the car for a long drive home alone. Especially at night, but really any time. Having Lucy in the back seat makes it suck less. She’s lived in three states with me, and at nine different addresses. She was there when my brother deployed (twice) and when my partner left (also, unfortunately, twice) and she was there when my niece came home from the hospital and when I came home after signing the contract for my first book. I know she hasn’t “shared” in these moments in the way a human being could have, but she accompanied me through them in a deep way and I’m grateful.

"She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman."

I love that your dogs show up in your first poetry collection May Day (Graywolf Press, 2016), like in the poem “Powderhorn, after the Storm.” This part is one I think most people with dogs can relate to (maybe too well – I winced remembering times I had lost my temper with my now-dead dog Pete; I think that regret will follow me a lifetime):

I jerked her leash, nudged

her through the door

with my knee. These cruelties

aren’t held against me.

I regret them deeply.

What is it about documenting regret in a poem that appeals most to you?

Sage

I suppose I felt like it was important to be honest about that night, and losing my temper with Sage was part of it. I didn’t know it until I had time to process it later, but I was irrationally angry at her that she was sick, and I knew that she wouldn’t be with me much longer. I was terrified to think of losing her. I’d raised her from a six-week-old; she’d been in my life since I was nineteen.

I had also just had a terrible, frightening day, and I wanted so much to be asleep. She’d woken me up, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to fall back asleep. The power was out everywhere and it was hot, and there were constant sirens. I still regret it. Sage was such a good dog. She deserved so much better that night. Letting myself off the hook in that poem would have ruined it.

So much of May Day is in conversation with the interiors grief creates (to quote one of many examples, in “About Suffering”: “there are so many / places for grief to live that we can’t note each address”). These poems trace the ending of a romantic relationship, the worry over your brother who was deployed to Iraq. And it seems that animals are a language for grief in this collection – the deer wandering through these poems (which we’ll talk more about in a bit), the macaw and painted turtle, the cardinals in the poem “Red.” Can you talk a bit about how animals helped you excavate this rawness, this vulnerability in your work?

I lived outside of a small town in a wooded area, and there were animals everywhere. There would be hoofprints in the sandbox some mornings, and the railroad tie retaining wall behind our house was full of toads. There were skunks, and raccoons, chipmunks and squirrels – I saw them every day. Sometimes terrible things happened to these animals. They got sick and died. They killed each other. They were hit by cars. I don’t remember processing any of this, but my dad told me that when I was two, I would remind him, every time he drove away from the house, not to “bump the deers.” So their well-being was an early concern. They were vulnerability personified.

I also think (and this might have to do with my deer imagery issue as well) that watching a deer skinned and dressed in my neighbor’s yard when I was small was shocking and transformative in a huge way for me. For one thing, it changed how I thought about bodies, including my own.

I have used this quotation many times in connection with stories about what might have led me toward poetry, but it has never stopped feeling right to me. Alan Williamson says that, “for many of us, the moment when we experienced something we could not share with our outer world, because our outer world had given us no 'word' to acknowledge it, was the moment that impelled us toward poetry. And poetry was a struggle with the given language, to make it give us better words than 'unlikely' for what had fallen out of this world’s likelihood.” I think that’s the truest statement I’ve ever read, and my earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals.

"My earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals."

True or false: To love is to grieve in slow motion.

False. I feel they are separate. I’ve actually spent a lot of time thinking about this! I prefer to think of grief as being powerless to negate or eliminate beauty or joy, and I’ve also accepted (more or less) that beauty can’t eliminate grief. Grief is not going anywhere – there’s always more to come. But there’s a good insurance policy in that. If grief and joy can’t touch each other, joy is protected, and there will always be more of that, too.

Lucy is going to be sixteen years old in December. In August, they thought she had a mass in her bladder, and for a few weeks I was wiped out with sadness and worry. It turned out that wasn’t true, and now she’s healthy again. But I know she can’t stay forever. Every day, I cook ground beef and mix it with pureed pumpkin and mix it with her dog chow, to help keep her weight up. Every day it makes me happy to watch her eat. She wags her tail the entire time.

When I was reading May Day, I started noting in the margins “Gretchen’s deer” whenever one popped up. Let’s look at “Deer Suite” in particular, where the deer is directly tied to the theme of want that drives so much of this collection:

If I say my longing is a doe,

that it bounds,

that it chokes, has parts that splinter,

that it can be split

from breastbone to pelvis.

(I love how seamlessly this connects to the epigraph in “Doe,” a poem that appears earlier in the collection: “A Wounded Deer—leaps highest—” from Emily Dickinson.) Let’s talk about longing and want and when you first realized that theme would shape this book.

I think that theme has shaped everything I’ve ever written and will continue to do so. About a third of the poems in May Day were taken from my thesis. At the time I was really interested in those lines of Rumi’s – “There are love dogs / no one knows the name of. // Kill yourself / to be one of them.” I heard another poet use them once in the spirit of romantic adventure and they rang a little false to me. I don’t think we all get to be love dogs.

The poems I was writing during graduate school were about the partner I was in love with, and about Lorca, and about my little brother who is a soldier. They were about my own broken heart. I wondered if we were all love dogs, and if the condition of being one comes and goes, or if it really is a choice, as the poet I mentioned above seemed to think it was. I still don’t know. But this idea of longing plays into that directly.

During graduate school I wrote a poem called “Love Dog” (and, in fact, that was the title of the manuscript I first turned over to Jeff Shotts). The poem was about the first dog I ever met who was afraid of me and didn’t want to be touched. It was the dog that belonged with the family who bought our house in the woods. I had reached out to pet the dog and she growled at me. Her boy held her collar and apologized, and then said, “Some people hurt her for fun,” and then told me that she had been a stray, and that someone had shot her with BBs and they were still under her fur when they found her, running loose.

I realized there was nothing I could do to prove myself to this dog, and I saw myself for the first time as an unknown quantity to another creature. That I had the capacity to hurt someone else. She didn’t get to be a love dog. Things have happened in my life that have made it harder for me to be one, too. Is that a failure of courage or character? I don’t know.

Even though this seems to be getting off topic, I don’t really think it is. I want to be a love dog. I long to be one. And sometimes I feel like I am killing myself to be. But what I really wish is that I could be a love dog and also not kill myself.

"I don’t think we all get to be love dogs."

What are you absolutely obsessed with right now? It can be anything, not necessarily poetry or animal related.

I’m obsessed with cave paintings, with the spacetime continuum, with images of The Madonna, and with origins of human mythology and our earliest attempts at situating ourselves in the world. (I’ve been reading Joseph Campbell.)

What’s changed the most for you since your first book came out?

I suppose that it’s been an adjustment to realize, after so many years, that my poems have an audience. For so long it was just my classmates and my teachers. I’ve met new people because of my book; it’s brought friends and opportunities into my life. In some cases, it gave me a deeper home in poetry, and a chance to connect with other poets I deeply admire – some new to their audiences like I am, and others who have been heroes a long time.

Advice for poets staring wildly at the expectation of a second book and coming up short?

I’m working on my second book, too. Some days I feel like I have an answer for you, and some days I want you to tell me what others have to say on the subject!

I know that for me, the process is different than it was when I was writing May Day. I’m much farther removed from my academic community, and I’m working differently because my life as a poet has changed (see above). When I’m writing a poem I have to remind myself that each one deserves its own space. Every poem won’t make it into the book; I have to let the poems arrive, whatever they’re about and whatever form they want to take. That said, it is fun to watch a book arrive slowly – to see themes and motifs materialize. It helps me understand myself and the life I’m living.

I would say trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something.

It’s also a good time to rest, especially if your book just came out. I like intentionally taking time away from writing and using that time for reading. Collections of poetry are always inspiring, but nonfiction books also bring a lot to the surface for me. I just work hard in my writer’s notebook–taking notes, jotting down ideas or lines, etc. During my writing vacations, either what I read will inspire me, or the obstinate part of my brain that’s been told it can’t write for ten days will suddenly find itself very active. It works most of the time.

"Trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something."

A metaphor or simile for Lucy?

Lucy is my home.

Brandon Jordan Brown: Satan Must Love Animals

Poet Brandon Jordan Brown on his cats Wyatt and Little Bear, writing about spirituality, the absolutes that exist for him in poetry, and the one statement about poetry he can stand behind for five (or 50) years.

I'm going to keep this introduction short and sweet because I am so excited for you all to check out this interview with Brandon Jordan Brown, a poet whose craft is outshined only by his generosity – and maybe his cute kitties. Friends, I even stole the title for this interview from a line of one of his poems because I love it too much. I had the singular honor of chatting with Brandon for a few hours about everything – growing up in the South, how animals help define a place in his poems, religion, schools of poetic thought, and some advice any writer would be wise to remember.

DID I MENTION HE HAS A KITTEN RIGHT NOW? Let's do this.

Some background: Brandon was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in the South. He is a PEN Center USA Emerging Voices Fellow, winner of the 2016 Orison Anthology Poetry Prize, a scholarship recipient from The Sun, and a former PEN in the Community poetry instructor. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Grist; Scalawag; Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review; Forklift, Ohio; Day One; Winter Tangerine Review and elsewhere. He currently lives in Los Angeles and you can follow his work here.

Note: The following interview has been edited for both length and clarity. Enjoy!

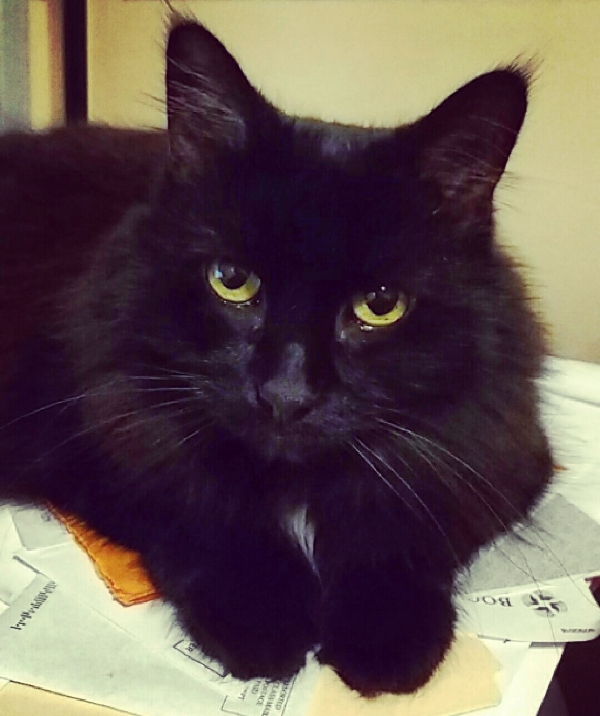

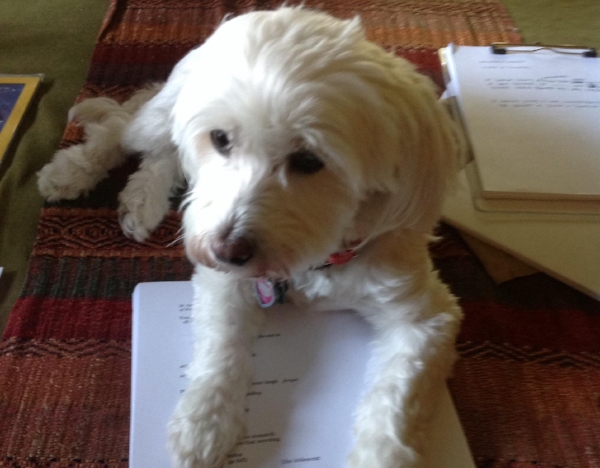

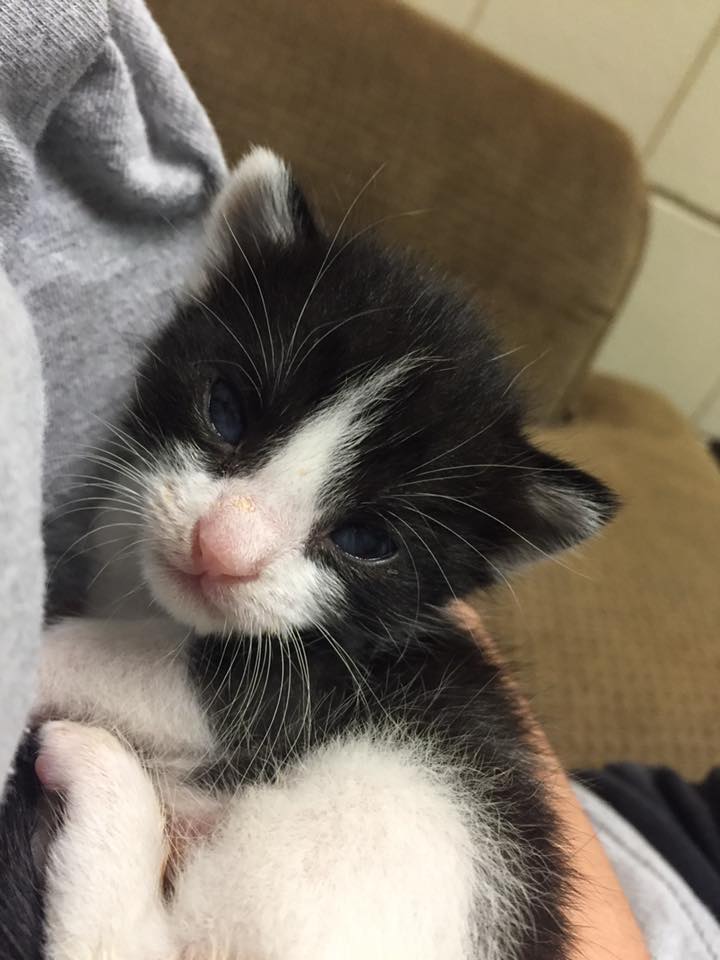

Photo: Little Bear, a tortoise-shell baby cat, sitting on stack of books on a desk.

I guess this is a good time to ask about your cats. So tell me everything – how your cats came into your life, how they changed things for you – everything.

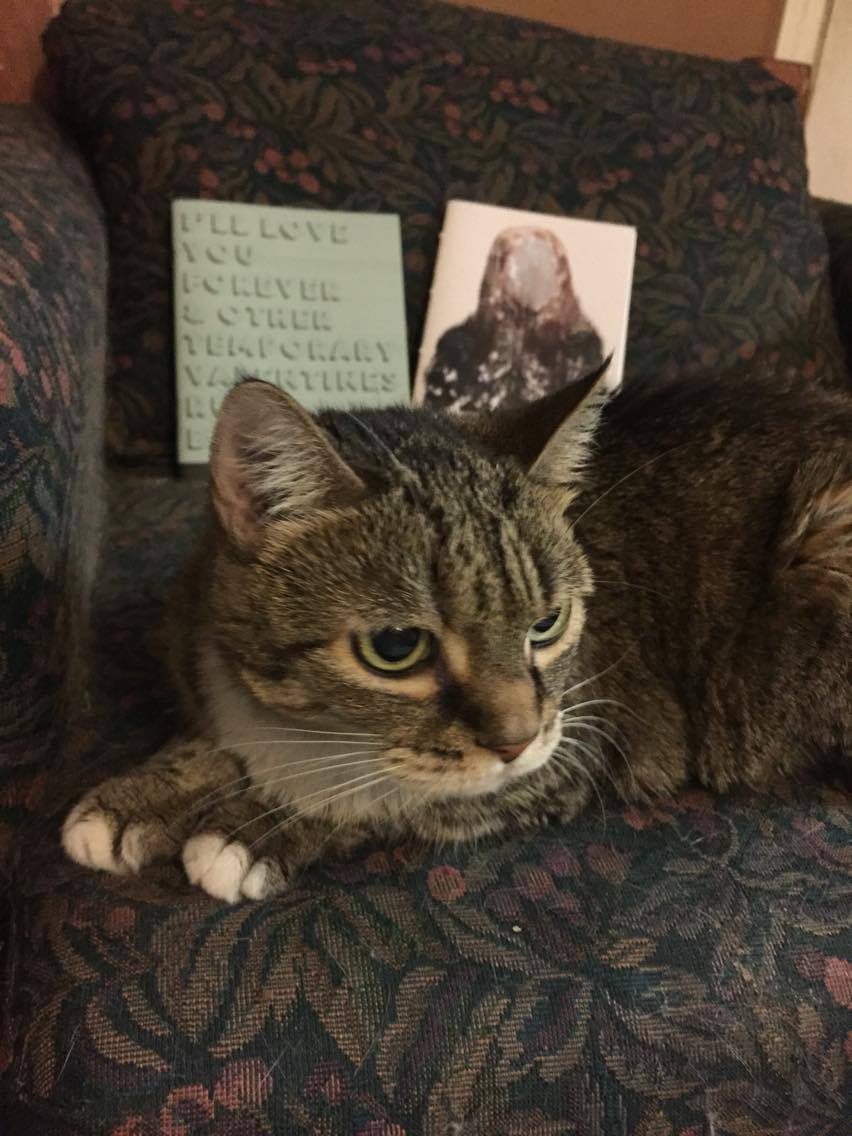

We have two cats. The older brother, his name is Wyatt. He's a tuxedo cat, and we adopted him from a shelter out here a little over a year ago when he was a few months old, and he is such a unique cat. He is a very needy cat. He is very high maintenance, but he's such a sweetheart. He wants engagement and play, but that can be tricky when you're not always able to offer it because you have to go to dinner after work or you make plans to go on a date or go hang out with friends.

And we made the decision to adopt another cat so he can have a friend. So we were at the vet getting Wyatt a checkup because of his behavioral issues and told the doctor we thought about getting another cat. And they said, “We have some kittens in the back that you should come check out.” And that's where we found Little Bear. She’s brand new to our family. We've had her for a little under a month now and she's tiny, tiny, tiny, a little tortoise-shell cat. And she's been so good for Wyatt. Wyatt has a friend, we have more love in the house. Last night, I was sitting in a chair in my living room with her asleep on my lap and him asleep on my chest. And I had achieved a rare moment of joy. Like I was I was fully in a moment.

And we only have plans to get more animals. We would really love at least one dog. Having a goat would be rad. I have big dreams. Give me a cow. Give me everything. I want it all.

My favorite piece of cow trivia is they have best friends.

That's amazing. And I think, too, the idea of having animals is almost synonymous with a certain pace of life. Like having pets and being able to tend to your pets is a sign that you have enough space in your life to care for something and to develop a relationship with something. I think that is one of the most powerful things about what it means to have animals – this ability to take time to be slow. Especially living in the city, that can be very hard. And coming from where I grew up [in Alabama and Tennessee], it's almost like it has a heavy symbolic weight, that idea.

"I think that is one of the most powerful things about what it means to have animals – this ability to take time to be slow."

That falls in line with something that I always tell people about what changed in me when I got animals, and it's that caring for animals takes you out of yourself, you know? It gets you off your bullshit.

There's something unique about that: pulling you out of yourself to care for something. I mean I even see it in [my] relationship [with my wife]. It's like only one of us bottoms out at a time because as soon as one of us does, the other person snaps to attention to care for that person. I think we do the same thing with pets, too.

Pets are magic. So let me ask you: have your pets ever influenced or inspired your poetry? Specifically, I want to ask you about your cats inspiring some of the lines in your poem "Satan," which is amazing:

The sun has a particular way of cutting

through the blinds and lighting up

the cat’s spine. That sunlight is all Satan.

And so I must make peace with two hells cooking me

at once: the hell below me and the one above

this ball of light and its army of swirling moons. Now I hate birds.

And this wonderful line: “Satan must love animals, too.”

For some reason, it's kind of rare that I write about things that are happening in the present for me. I almost have this feeling the things that need to be in my poems need to have some sort of sticking power so that I'll be proud of them sticking around later, I guess.

But animals from my childhood make an appearance in my poetry. I have poems with my Papaw's goats or the cow in the backyard that he got angry at and he punched. And because a cow is much stronger than my Papaw, it broke his hand. Just standing there, being a cow… So I have animals that pop in and out of my work all the time. But I'm in a season of writing right now where I'm focused a lot on recalling memories from the past and sorting through all that. So maybe I'll have some really good poems about Wyatt and Little Bear in like 2020, 2022. Look for them; they're coming.

Photo: Wyatt, a tuxedo cat, looking up at the camera with soulful eyes.

You know, some people sit down and write every single day. Maybe that lends itself more to poems born of the present. I write whenever I feel like it, and I usually reach far back into my most painful past.

So are we in the glutton for punishment school? When people talk about literary movements, is that where our names are going to pop up?

You know, I hope that my name pops up under that school because I would be very proud.

Because our last names are close, we may be near each other in the list. We may be just a few commas away.

That would be a really great anthology. So hold on that idea and then take my work.

It's really just you and me dialoguing back and forth about being super sad.

Being sad and loving animals.

That's it. A great working title.

My follow-up question: I was reading every poem of yours I can find online. And in your poems "Boyhood" and "Biology," I notice that you use animals to help tell a story about a place's values and also about masculinity and its expectations. For example, in the poem "Boyhood," you write:

This is how things are to be done. How a man is to be made: by pushing

logs that fall from the backs of trucks into the ditch across the road and

whipping the mutt that follows you to the mailbox each day

until it feels thankful and a little scared to even be alive.

So I was hoping you would talk about the relationship between animals and place – how you use animals in poems to help shape a place and its mood and its values.

Animals, they're so intimately connected to a place. How they share space with you. I grew up with animals everywhere. Like lightning bugs – those don't exist in other parts of the country, but I know what they are. And I remember having memories directly connected to an animal that doesn't exist other places. And my home in Tennessee – we always had dogs and right beside us was a field full of cows. And then you'd go visit your grandparents and there are more animals down there, animals to be afraid of and animals to get excited to see. For the sake of writing, they almost can become a literary device in a way to pull out the feeling.

I think there is something about our relationships to animals that closely mirrors our relationships to each other. So a defenseless, even confused or clueless dog getting beat – that's only a small subset of things that we do to each other. And that's both in the tenderness that we show and in the violence that we commit against each other. You look through history, and one way that we oppress whole groups of people is to liken them to creatures that are not human. On the other hand, we call people we love pet names, right?

"You look through history, and one way that we oppress whole groups of people is to liken them to creatures that are not human. On the other hand, we call people we love pet names."

Exactly! So I read that you are working on your first book of poetry. Do you want to talk a little bit about that project, the scope?

I have a chapbook manuscript that is done – several of the poems that you've mentioned are in there. And the big thrust of it is really some of the themes that you nailed down just by reading a couple of pieces that you found online. It deals a lot with growing up in the South. That is my whole lineage, I guess, that's the place that shaped me in a lot of ways. Maybe even in the most unconscious of ways, the most subtle and unexamined of ways.

And I didn't even realize until I was ordering the manuscript how big the theme of manhood or masculinity was until I started looking at it as a whole, cohesive unit and having other people give me feedback on it. I had this idea that it was about faith, a lot about the landscape, a lot about family, relationships.

One of the themes is based off of Saint Augustine's understanding of sin, this idea that your love is out of order, the things that you are pouring your love into are disordered. And so you need to reorder them to flourish or live the best life. You have to pour your love into the right places. So the book is a wrestling with what it means to love someone or something. How do I do that, and in what order? That's how we end up spending our life, I think – trying to figure out how to do that.

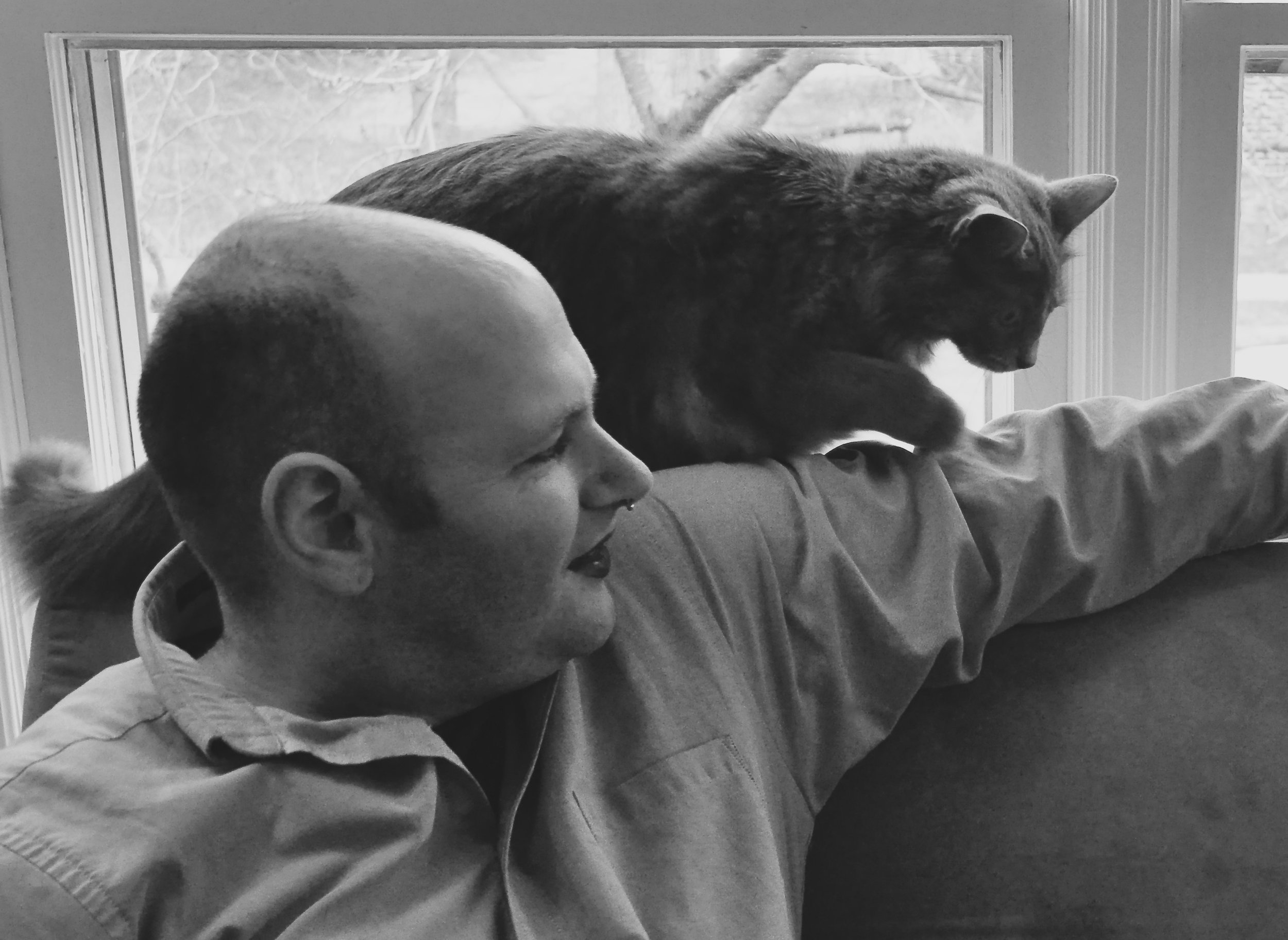

Photo: Brandon with Little Bear, faces together.

I never thought about that before and I really like that concept. I kind of hate to think about how much of my time and effort I pour into like my job, my work. So in your own life, where do you think you're placing your love and do where you want to place it?

Oh my gosh. That question is terrifying. I guess one of the questions that I have a lot is: how much love do I place on myself? Because that can be a very tricky question to answer. And I think maybe there's a thing in me, there's an impulse in me, that says leaning too far in either direction is wrong. Like overly loving yourself at other people's expense or self indulgence or super ego-driven narcissism – I never want to lean in that direction, but I also want to be kind to myself. I had a mentor one time tell me that I needed to talk to my own heart like I would a friend because we can be so hard on ourselves. And I want to be able to do that.

That is such a difficult balance to strike. Can I ask a prying question? Do you consider yourself a religious person?

I do. So I got into religious studies, thinking that I would maybe take a more traditional, vocationally religious life trajectory. And as I moved further and further in that direction, it started to feel less like a full expression of who I am. That is a part of me. And even if that's the central part of me where everything else flows from, in many scenarios, there's only one way that you can show that side of yourself. And I feel like through the arts, I'm able to do it as a much fuller expression of who I am.

Are there special considerations you make when writing about your faith? I'm angling at how you approach writing and engaging with your spirituality on the page.

I mean, to put it bluntly, all I think about is God. That's I think a really succinct statement that requires a ton of unpacking. That's my chief source of questions. If you're taking faith seriously, it necessitates so many questions – like how could we imagine that we can easily encapsulate the infinite?

"Poetry is a long game... I don't have to say it all at once."

You could write about that for a lifetime and never be done. Ok, here’s a hard one: make a statement about poetry you think you could stand by for the next five years.

What a rad question. I think for the next five years, you could confidently walk up to me at any moment and I would always say, I should be writing more. That is definitely a statement I will probably be able to say in the next 50 years.

You could put that on any poet’s gravestone.

"Should've wrote more. Could have been a contender." I guess some advice I give myself all the time – and this is maybe less about the effect of poetry and more about the practice of writing poetry – is that you don't have to say it all at once. That poetry is a long game. And I think that makes me feel better when I start getting anxious about my output or my momentum or my personal satisfaction with how often I'm writing or investing in the community. I think that's advice that is always good for me remember: I don't have to say it all at once. When you're a poet, you don't retire from being a poet. And that gives me a lot of comfort.

Is there any particular subject that you absolute won't write about? Do absolutes even exist for you in poetry?

I don't want to co-op someone's story or use someone else's pain for some strange artistic benefit because we see that a lot in the history of writing. We still see it happen today, and there are a lot of really good conversations happening around that idea. And I don't want to be a person who does that. When that happens, something about the work has gotten off track, whether the writer realizes it or not. I don't want to make that mistake, so I think about it a lot. Like, I've started this project where I'm working on a series of persona poems, so I've been asking myself, why do I want to do this project?

Photo: Wyatt on Brandon's shoulder.

I feel like poetry and memoir have always kind of dovetailed, but maybe even more so these days, you see a lot of memoir's influence in poetry. And I know for memoir, that's a huge question: what stories do I have a right to tell, what stories are mine?

I feel like throughout our whole conversation, everything feels like to me it's this question of interrelatedness and neighborliness. A lot of our conversation today has been defining our relationships to things or other people that orbit in our sphere. I guess to bring it full circle, in the New Testament, there's this question that gets posed: "Who is your neighbor?" It's kind of a rhetorical question. The whole point of the story is to basically point to the fact that everyone is your neighbor. And we're supposed to treat our neighbors with dignity and love and respect, and I feel like that's kind of one of the central themes that keeps popping into my mind in this conversation – this question of like neighborliness to animals or people. And it's really interesting.

You tend to look outward with your answers, which is really refreshing. I really appreciate when people have that worldview of looking beyond themselves consistently.

I hope so. Long may it continue! Thank you. I guess I should just say thanks.

"Everyone is your neighbor. And we're supposed to treat our neighbors with dignity and love and respect."

So I watched the videos for a couple of your poems on your website. I was wondering if you had a background in visual art? And what’s the process for pairing poetry with visual imagery?

So before I found my way into writing, I was a musician in high school, in college. I started learning the bass guitar in eighth grade, and in high school, I joined my first hardcore band and I was the screamer in this hardcore band. When you’re in a band, it matters that you have T-shirts. It matters that you put on a good performance as opposed to just writing good music. And I think because I have that background, I'm just very interested in how things look. And so I think a video can be a really cool way to bring some of those elements in and to connect with people who are maybe even too intimidated to read the poem on the page because they don't know how to approach it. And so video could be a really cool way to kind of bridge that gap and jump over that threshold.

The guy who I shot those videos with is a buddy of mine, Dru Korab – he's an amazing filmmaker – and we have plans to make more because if it's really about making an impact, getting your work into the world, and making some sort of contribution, then I think collaborating with other artists who have that same impulse in a different medium can be a really cool way to do that.

I’m going to talk about Beyoncé for a second. My favorite parts of Lemonade are when she reads Warsan Shire's poetry. The images paired with the spoken word is some of the most striking stuff I've seen in a long time. I really love how visual imagery can elevate the imagery in the words of the poem.

Yeah, totally. Maybe some people are nervous because they're afraid that it will supersede the poem. But that is the artistic process of figuring out how to say it best. We cut and add new words and phrases all the time to our poems. I think if you're even approaching the visual component like that, it can be similar. It doesn't have to overcome the poem. It can be a nice complement.

It also makes poetry accessible for people who depend on listening to experience poetry, too.

That's a super great point for sure.

Photo: Close-up of Little Bear, her paws stretched out in front of her, looking unbearably cute.

Are you ready for your final question?

Let's do it.

I need a metaphor or a simile for Wyatt and Little Bear.

I'm going to say that Wyatt by himself is a single tooth in a mouth because I think all of the proper elements are there. But our experience with him is he cannot do his best alone, he cannot be his best alone. So he needs another tooth. You're not chewing any food with one tooth.

Little Bear feels like a bubble that won’t burst. Where the whimsy and the exploration and magic is there, but I also don't have to fear that it will burst suddenly.

It's just so, so cheesy, right?

Susannah Nevison: Renaming the Body

Poet Susannah Nevison on her pup Ella May, how her poems aim to resist typical disability narratives, and how animals help her tell that story.

I was just reading in The New Yorker "Are Disability Rights and Animal Rights Connected?," a piece that profiles disability and animal rights advocate Sunaura Taylor and her work as a painter and an author – specifically, how her art explores the contentious "space where disability and animality meet."

It's worth a read, and afterwards, my thoughts immediately circled back to this very interview with Susannah Nevison. It's not that Susannah's ideology aligns with Taylor's – I can't speak to that. But like Taylor, Susannah says her work aims to resist typical disability narratives, the ableist inspiration stories and the ones where the body is "fixed" and assimilated. And animals help her tell that story, too.

Before you hear it and meet her beautiful dog Ella May, I want to thank Susannah for her latest book, which you should read immediately. It sticks with you, every poem.

A bit about Susannah Nevison before we dive in: she is the author of Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry. New work can be found in, or is forthcoming from, Crazyhorse, The National Poetry Review, 32 Poems, Pleiades, The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, Guernica, and elsewhere. She is a Clarence Snow Fellow at the University of Utah, where she is a doctoral candidate. For more information and links to her work, you can visit her at www.susannahnevison.com.

Photo: Susannah's dog Ella May, a pit bull mix (possibly basset hound, dachshund, or beagle, says Susannah), wearing an orange bandana with a vest that says, "Adopt Me."

I know you mentioned you don’t know much about Ella May’s backstory other than she was found on a street. If you had to invent one for her, what would it be?

Ella May is named after a fictional character, Ellen May, on the show Justified, based on Elmore Leonard’s Fire in the Hole series. Ellen May is a sex worker. Her character begins as a stereotypical “stripper with a heart of gold,” but she’s quickly shown to be someone much more layered and nuanced. Our dog is similarly complicated, and there’s part of her that is just so unknowable—she is, after all, a dog—so I always wonder what’s really going on inside her head, where she’s been, and what she really thinks of the world.

I like to imagine Ella May as leading an itinerant lifestyle akin to her namesake’s—maybe she was a boxcar dog, riding the rails and taking in the views. I like to imagine she got off the train in downtown Salt Lake, trotted right to our front door, asked for a room, and hasn’t left since.

Do you ever write about Ella May, purposefully or otherwise?

I don’t ever write about her. I talk about her, and to her, all the time. And I write with her—she’s either at my feet, or seated next to me with her chin or a paw on my lap.

Let’s talk a little about your (stunning, otherworldly) collection Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), a book teeming with animals – there are bats and birds and wolves and foals and horses. We begin with “My Father Dreams of Horses,” the first in a series of poems by the same title. In a book that covers thematic ground like myth, surgical trauma, disability, identity, and family history, the horses here seem almost prophetic:

if you wade into the horses—

if flames—if you cannot keep

her from burning—if she will not

keep—if the horses burn—

if your daughter is born—

Can you talk about the horse as a symbol in this collection and perhaps their connection to the medical history referenced throughout?

Many of the poems in Teratology are reimagined encounters with my extensive medical history, and the ways in which that history intersects with my father’s extensive recovery from severe burns. The opening poem you mentioned hits on both these threads—congenital trauma and my father’s fire accident— and I hope the poem serves as legend for the book that follows.

One of the birth defects I was born with is very common: clubfoot. The medical term for it is talipes equinovarus, which roughly describes the foot’s abnormal shape. A clubfoot is turned in at the ankle, and elevated at the heel like a horse’s foot. I am fascinated that we call congenital birth defects teratogenic—from the Greek for monstrous—but we give these so-called monstrous defects names that describe them in desirable and beautiful forms, such as a horse’s foot. Of course, practically speaking, it’s undesirable for a human foot to be horse-like, but the idea that we name the defect after the place in nature where it is useful, where it makes absolute biological sense is so striking to me. I wanted to use the clinical language of my diagnoses to refigure the disabled body. What might it look like, for example, if the disabled body—at least symbolically— possesses all the strength and wildness of the language we attach to it? What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative— medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself? What if the father figure, himself a trauma survivor, imagines his future child’s disabilities in that shared language?

"What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative—medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself?"

Photo: Ariel view of Ella May lying down, looking up at the camera, one ear pinned back and one pointed skyward.

In “Bestiary,” you write, “You walked / into the wolf’s mouth and you were lost: / as in all good stories, they claimed / you for their own.” So much of this collection is about who lays claim to the speaker’s body. Can you talk more about this guiding question?

Bodies are complicated. Disabled bodies are especially so, since they are always in some way at war with themselves or their environment. As someone who started having surgery when I was five-months-old, I’m the product of extensive medical intervention—I am, quite literally, shaped by surgeons’ hands. In many ways, this is an enormous gift, because I’ve been able to engage with my environment in ways that seemed impossible at first (I wasn’t expected to ever walk, let alone lead the active childhood I eventually did), and I’m incredibly grateful for all the experiences that surgery has given me access to.

But that access—as granted by medical intervention—does have a cost. Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me. I’ve only known my body as it was made and refashioned by medicine, and as it resisted those procedures. It’s a strange kind of grief: knowing that your body isn’t made for the world you live in, or the life you want to have. But there’s also a strange kind of joy in knowing that you can, quite literally, be remade and reborn, although it doesn’t negate the shame or guilt that comes with living in a body that won’t “behave.” Writing Teratology became about reconciling my gratitude and awe for—and my dependence on—medical intervention with my accompanying grief, shame, and dissociation that comes with inhabiting a body that never feels like it’s mine alone, and one that others deem deviant or wrong.

"Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me."

Photo: Close up of Ella May sleeping on a purple blanket, one paw next to her face, books on bookshelf in the background.

Let’s take a look at “Lore,” a poem that draws an explicit connection between the speaker and an animal, in this case a stillborn foal:

…isn’t this the way

I was born, the wide dark trembling, a swell

of blood pounding across distance,

forcing inlets between bone?

They say I was tied like a calf,

legs knotted for stumble. They say

I was a strange, mute animal.

It seems to me that the animals in this poem and throughout the collection help illustrate ableist world views and their othering, destructive effect. How do you think these poems engage with that history and present?

I really wanted Teratology to resist typical disability narratives—ones wherein a body is diagnosed, fixed, and then happily at home in the world, or ones where the disabled body is tragic, a mirror for what scares or threatens the able-bodied world. To do that, I tried to give the disabled body the literal wildness of its clinical diagnoses, to let the disabled body kick and keen and rage against the constraints imposed upon it, medical or otherwise. So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies. Many of the poems in the book became an exercise in reinventing and refiguring spaces through the disabled gaze, while the disabled body undergoes its own encounter with the medical gaze. I wanted the disabled body, while undergoing medical intervention, to unleash its wildness in these spaces, to reinvent the world around it, even as it undergoes its own kind of reinvention.

"So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies."

Photo: Ella May sitting down and giving some serious side eye, wearing a green bowtie collar.

In poems like “Pre-Op Portrait with a Colony of Bats,” we see glimpses where the wild meets the man-made world:

They held the mask

over your mouth, pumped you

full of forgetting: the sky

fashioned a noose and hanged

herself, purpling and gasping—

Several poems in the collection deal with this fog of forgetting – through anesthesia, morphine – and the way this space blurs the boundaries of the lived-in world. Can you discuss this psychological space and why it’s rich landscape for exploring the body and self?

So many transformative moments happened while I was under anesthesia, and so it’s impossible for me to have any memory or recollection of these key moments in my personal history. The closest I can get is through my own medical records. That momentary space between consciousness and induced unconsciousness is, for me, one of my earliest memories. Most people, I imagine, have specific moments or events they recall as their earliest memory—instead, I have this weird non-event, this kind of fading away. I don’t have access to any moment of witness, but I do have access to the memory of losing that kind of control and autonomy. The act of witnessing, in this collection, had to take place then in the moments before and after surgical intervention—the interstitial spaces, as it were— and for me that became an essential part of disrupting the expected surgical narrative. I had to circle the large surgical events because I was, in terms of memory, absent from them.

You said in an interview with The Cloudy House, “I’ve always been trying to make sense of what it means to live in a body that is constantly undergoing revision—and how physical transformation changes not only one’s relationship to the world, but to family and identity.” Did writing these poems change your relationship with your body in some way? I read the final poem “If You Come to the Sea and You Must Cross” as ars poetica: “When the good work is done / you begin.”

Writing these poems gave me control over a narrative I can’t ever know completely, and in that sense, changed the way I think about my body. If I can’t know my history completely, I can at least invent and shape a narrative that feels the most true to my experience of the world and my body in the world. I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention. The last poem is very much an ars poetica, but it’s also an homage to the disabled body’s ability to reinvent and reshape itself.

"I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention."

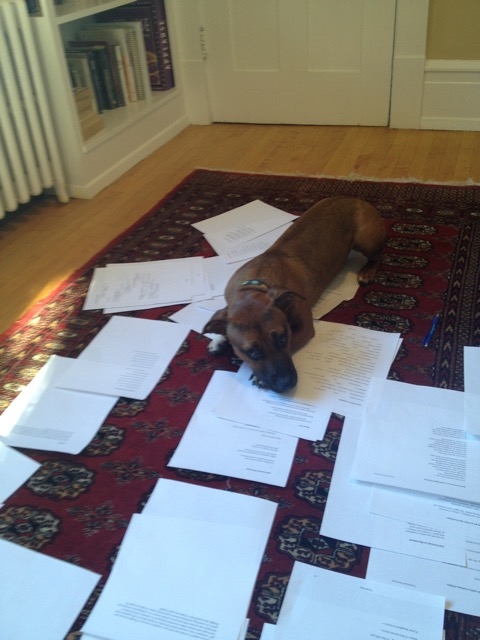

Photo: Ella May lying on top of printed poems laid out on the carpet, possibly helping her human with the editing process.

Was this a difficult collection for you to write, and if so, did Ella May’s companionship help you forward?

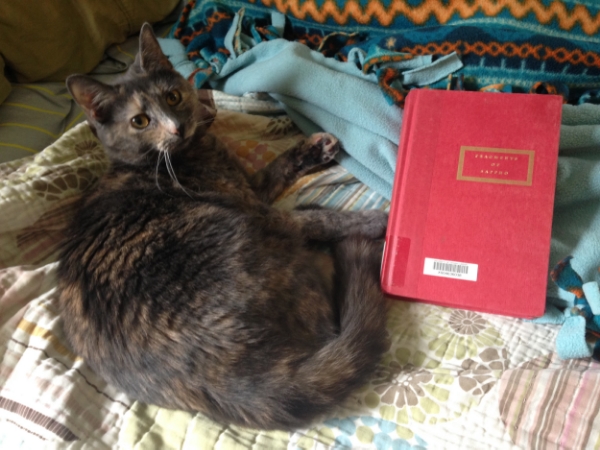

Yes, the collection was pretty difficult to write because so much of the material is emotionally fraught for me. This book was mostly written between dogs—we had to euthanize our previous pup in February 2012, the winter before we moved to Utah. We adopted Ella May in late May 2013. She couldn’t have come into our lives at a better time. I had just finished my first year of a PhD program, and was finally beginning to figure out how to make Utah, and the manuscript in progress, work. She was great company for the final stages of writing and ordering the manuscript. She helpfully stretched out across the pages on the floor, got dog hair everywhere, and rolled around on the floor noisily while I attempted drafts of the final poems. She’s a wonderful lounger and napper—something I also pride myself on—so she also snored loudly while I wrote. (I’m sure that helped keep my expectations for the book in check.)

A metaphor or simile for Ella May?

The best potato west of the Mississippi. A mismatched slot machine. The sweetest warthog you’ll ever meet. Everyone’s favorite, klutzy waitress.

David Winter: A West-Facing Window in Coal Country

Poet David Winter on his lovely cat Emily Cream McWinterson III, his hopes for what exists in the space between his lines, the best line of poetry he's ever written, the art of listening, what makes or keeps people safe, and more.

Photo by the exuberant Raena Shirali

I know you're here for pets and poetics, but let me just say: no one rocks deep-plum lipstick like David Winter. And that's not even scratching the surface of this surprising, talented, considerate person and poet. You'll see.

Here we talk about his lovely cat Emily Cream McWinterson III, his hopes for what exists in the space between his lines, the best line of poetry he's ever written, the art of listening, what makes or keeps people safe, and more.

A bit about David: he is a 2016-18 Stadler Fellow at Bucknell University, the recipient of a 2016 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, and author of the poetry chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013). His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Baffler, The Dead Animal Handbook, Forklift, Ohio, Meridian, Muzzle, New Poetry From the Midwest, Ninth Letter, Winter Tangerine, and other publications. His interviews and reviews have been published by The Journal and the Poetry Foundation. You can find more of his work here. And more pictures of Emily here.

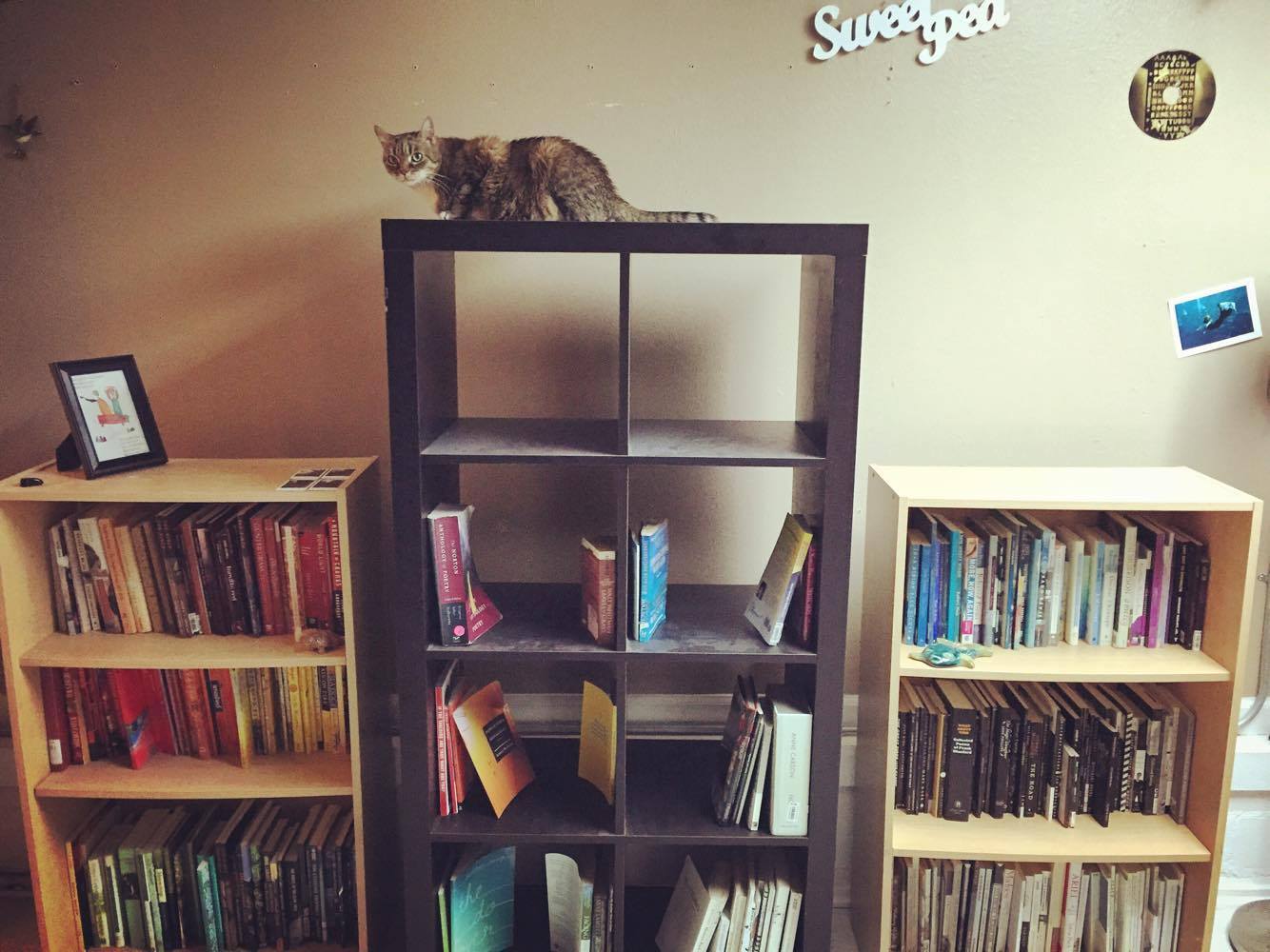

Tell us a little about your cat Emily Cream McWinterson III. I’m guessing she’s as regal as her name suggests?

Like most cats, Emily Cream McWinterson III occasionally strikes a regal pose, but like most members of long and illustrious lines (including imaginary ones), she’s also rather fussy. I don’t mind her fussing most of the time, but her insistence on talking about every step she takes and every craving she experiences does undercut the more dignified visual impression you get in photos. But if you’re the kind of person who likes talking to cats, Emily’s actually a very personable animal, and I think she really tries to be a good friend. There’s this idea about cats being indifferent to humans, but when I’m home and she’s awake, Emily rarely leaves my side. She’s very affectionate and also conscientious of boundaries, at least to the extent that a cat can be. I pretty quickly trained her not to wake me up too early in the morning. And after watching me scoop her litter into plastic bags a few times, she started trying to help by pulling the plastic bags into the litter box after she used it and burying the bags along with her droppings. Of course that actually made more of a mess, but I appreciated the gesture.

How has having Emily’s companionship shaped your writing life? It seems like she may be more than just a bystander to your work.

Emily has been a really important source of emotional support in my writing life. I adopted her shortly after moving to a small town in central Pennsylvania for a fellowship at the Stadler Center for Poetry. The fellowship itself and becoming a part of the the creative community that the Stadler Center cultivates has been an enormous gift and privilege—one I wouldn’t trade for anything. But as a queer Jewish poet who had lived my whole life in or around cities, when I suddenly found myself in the middle of coal country during the 2016 election season, I felt pretty anxious and isolated. I’m a fairly anxious person to begin with—I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and social anxiety disorder as a kid, although I’m ambivalent about what those diagnoses mean—and I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done.

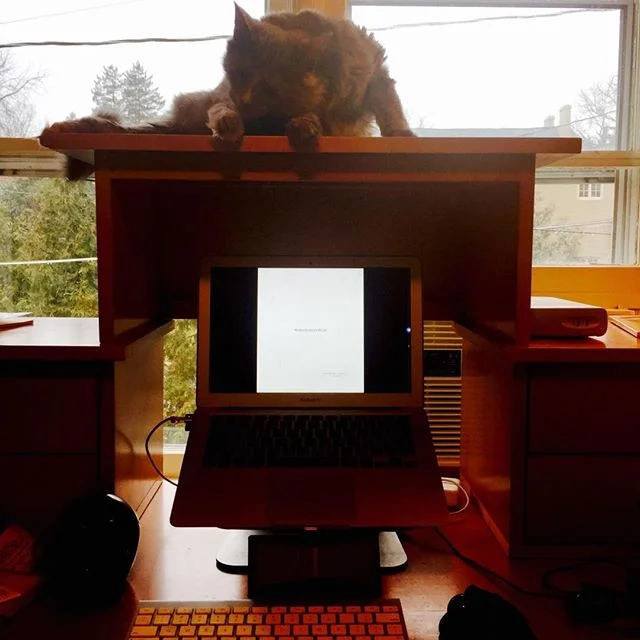

After I adopted Emily, I positioned my desk in front of a west-facing window, and the desk has a built-in shelf above the computer that gets some sunlight in the morning. I usually write for a couple of hours in the morning while Emily lies on that shelf, soaking up some sun and watching the birds, or just napping. It’s really an ideal arrangement because I can enjoy her company while I write, and she’s usually comfortable and occupied enough that she doesn’t walk all over the keyboard while I’m working. I’ve learned that when I feel too anxious to write, I’m better off taking a few minutes to play fetch with her and then returning to work more calmly, rather than opening up Twitter and panic-scrolling through the endless stream of news about the death-throes of American democracy.

"I knew that I needed to take care of my day-to-day emotional health if I actually wanted to get any creative work done."

I recently read your chapbook Safe House (Thrush Press, 2013), and I’m really compelled by its guiding question: “What makes a place safe?” Some poems seem to answer with the psychological (“Introductions” and “Lament With Cello Accompaniment”). Others explore or subvert safety as a physical space (“Parole”). And perhaps my favorite is how we find safety in others (“To Ask Our Bodies” and “Luciano Serafino’s Lover” – especially the line “Men like us / only ever find salvation in the dark.”). Can you talk about how you arrived at this theme?

Thank you for reading the work so closely. In some sense I’ve been thinking about this almost as long as I can remember, and I’m not certain why that is, exactly. I remember as early as second or third grade feeling very cynical about the social boundaries that were supposed to protect kids emotionally—the idea that if someone picked on you, you could tell them to stop or get an adult to protect you, for instance. That idea just seemed absurd to me, although I don’t think I was getting picked on or picking on anyone else all that much. But when I did get picked on, instead of confidently drawing a boundary, I often let things go until I got mad enough to hit back. Maybe this all has to do with being a queer kid before I knew I was queer, or maybe it has to do with my anxiety disorder, or maybe it’s something else altogether. I don’t know.

As I’ve gotten older, it has only become more clear that there’s no reliable adult stepping in to save us from ourselves or each other, and so we have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can. I grew up in what a lot of people would consider a safe and sheltered suburban town, and while I certainly benefited from the privilege that geography afforded me, there are also poems in this chapbook about watching one of my closest childhood friends smoke crack, and how my perception of the world changed the first time he came home from jail and told me what happened to him there. It was really during those years of late adolescence when I started to understand how the safety of the environment I grew up in was predicated upon barely concealed violence.

"We have to find our own safety, or some semblance of it, where we can."

In this chapbook, the poems are lithe and really put that whitespace to work. Henri Cole once told me (I’m paraphrasing here) that what goes unsaid in a poem can be as powerful as what we write. We were talking about Franz Wright, but I see this at work in your poems, too. Can you talk about the art of deciding what exists in the spaces between your lines?

That’s a great question. I think one of the hardest parts of learning to write poetry for me was (and is) accepting that I don’t entirely get to decide what happens in that space between the lines. Because it’s not just the space between the lines themselves, which would be a two dimensional space I could shape, and which might remain fixed and static once I’d shaped it. The space between lines is always also the space between the lines and a reader, which makes it a three-dimensional space somewhat beyond my control as a writer. And so I guess I’ve learned to make my peace with that reality by becoming almost obsessively controlling and deliberate with the language I do put on the page, in the hope that a reader will really engage with my work as they inhabit the imaginative space it creates. But I do think what happens there is ultimately up to the reader.

Here's a hard question: what’s the best line of poetry you’ve ever written and why?

I have no idea at all how to answer this question. Maybe because of what your last question was getting at—for me so much of what happens in poetry happens outside the lines, between the reader and the lines—or maybe just because I lack the distance from my own work to judge. But perhaps one answer is that the line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line. At any given moment the line-in-progress has the most potential energy; it has the potential to become something we’ve only begun to imagine.

"The line I’m writing, or the last line I’ve written, or the line hovering at the edge of my daydream, is almost always the most exciting line."

True or false: A poem can teach a reader how to listen.

True, so long as someone is speaking the poem. I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music. But I do think the poem must be read aloud; otherwise what we’re talking about is looking, and that is a different (although equally worthwhile) conversation. From what I understand most people subvocalize as they read—meaning they make imperceptibly minute movements and sounds—particularly when they’re reading something emotionally engaging or intellectually challenging, which poems tend to be. So I guess what I’m really saying is, yes, a poem can teach a reader how to listen, but the onus is on the reader to engage actively in that project.

What’s your favorite poem ever written about a cat? And do you write about Emily, either directly or indirectly?

I am working on a poem about Emily. It’s about two-thirds of the way finished and I can’t seem to figure out the ending, although I visit the text every week or so and try to figure out where it’s heading, what it wants. At first I thought it was about how much I loved her and also how fascism is encroaching upon and threatening everything we love, but I showed it to a poet I really admire when she visited the Stadler Center and she disagreed. She said it really just seemed to be a poem about a cat, or perhaps about a cat and how we hurt the ones we love. So I’ve been going back and forth on that for a while, exploring these different trails, but not quite finding my way. Who knows where it will end up, or if it will really end up going anywhere at all.

As for the other part of your question, T. S. Eliot’s “The Naming of Cats,” the opening poem in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, is by far my favorite cat poem. There are points in that book—as in pretty much all of Eliot that I’ve read—where his perpetual xenophobia and other prejudices not-so-subtly show, but the musicality of the language is top-notch, and it’s far more fun than most of his other books, and that poem in particular has a very strange wisdom to it. If he wasn’t so obviously a jerk, I’d give a copy of that book to every parent of young children I know, but alas, whiteness strikes again . . .

"I think listening is a practice as much as it is a skill, and we can learn to listen more deeply by listening to almost anything—birdcalls or poems or conversations overheard on the subway or political doublespeak or pop music."

A metaphor or simile for Emily?

Well, she didn’t turn out to be much like her namesake, Emily Dickinson. I suppose in some ways she’s more like Whitman. Her mouth never closes for long, but I’m thankful for that, because she contains multitudes.

J.P. Grasser: Wildness & The Indescribable Realm

Poet J.P. Grasser on his dog Gus: "When I’ve lost myself to the pure pleasure of writing, Gus happily reminds me of all the multitudinous joy & pain & love & suffering going on, at that very minute, in the space outside the margins."

I once told J.P. Grasser that I wanted to live in his brain for a day, and I stand by that. You're about to see why. We talk about his dog Gus, the connection between our desire to tame both poetry and animals, Keats, Herrick, Counting Crows, and Flannery O'Connor's peacocks.

Hold on to your hats!

First, a little about J.P.: he attended Sewanee: The University of the South and received his MFA in poetry from Johns Hopkins University. He is currently a doctoral student in Literature & Creative Writing at the University of Utah, where he teaches undergraduate writing, serves as managing editor of Quarterly West, and helps curate the Working Dog reading series. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in AGNI, Best New Poets 2015, Cincinnati Review, West Branch Wired, The Journal, and Ninth Letter Online, among others. He will begin a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University in Fall 2017. Find more at www.jpgrasser.com.

Tell us a little about your dog Gus. Maybe a story that exemplifies his role in your life?

Gus: (named after Gustav Klimt, the Art Nouveau painter, and/or Gus-Gus, the rotund & ruddy rodent from Disney’s Cinderella).

Gus: sweet & caring, regal & dainty, wild & vicious.

To elaborate: one afternoon last March, while teaching, I received a flurry of phone calls from my partner. When I managed to get in touch, she was beside herself, nearly inconsolable. She & Gus had been hiking on the Bonneville Shoreline Trail—a tract along Salt Lake City’s east side, which had once been the shore of the Bonneville inland ocean, a tract which is now mostly domesticated. Mostly.

As she tells the story, Gus had been trotting at her heels with all of his characteristic amiability—just enjoying the early spring weather, taking in the new smells, soaking up the good light. In a flash, he dove into the scrub brush. Just as quick, he re-emerged with a Magpie firmly in his maw. She got to him just in time to see an iridescent, blue-tipped wing disappear down his throat (whole).

When the scene wrapped up, he returned to Maggie’s side, calm & sweet as ever.

Getting to know Gus, watching our lives interweave & imbricate, has been much like this. He possesses a ferocity of spirit, an untamable instinct, which I admire. Which I’d like to emulate. And yet, there’s a grace in him too. Which I’d also like to emulate.

"No good poem can be written in this way—we must, I think, have one foot in this world & one in that other, indescribable realm."

Where does Gus fit into your writing rituals?

At first, he didn’t. Gus is nothing if not a fetch-fiend, and I usually like to write outside. Which meant, of course, I couldn’t get a thing done. Outside time, for Gus, means playtime. He never gets tired of it.

So, like him, I’ve learned to adapt. I write at the kitchen table most days now and, at times, forget he’s here. That is, until he decides to curl up at my feet.

This has struck me, of late, as a metaphor for the process of composition in general. For us, as writers, when all cylinders are firing in tandem, there’s a breed (pun intended) of absolute absorption that occurs. We forget the world; our psyches recede from it. But no good poem can be written in this way—we must, I think, have one foot in this world & one in that other, indescribable realm.

When I’ve lost myself to the pure pleasure of writing, Gus happily reminds me of all the multitudinous joy & pain & love & suffering going on, at that very minute, in the space outside the margins.

In our pre-interview banter, you noted you saw some connection between how we engage with poems and how we engage with domesticated animals. In essence – please forgive the rough paraphrase here – our aim seems to be to contain both a poem’s and an animal’s wildness. But as you said, “Wildness can exist in even the well-mannered poem.” Can you elaborate on this connection?

Yes! Advance apologies for the grad-school density to follow:

In The Well Wrought Urn, Cleanth Brooks gives one definition for poetry as “the language of paradox.” Or, to go the Keats ‘Negative Capability’ route, one might say good poetry is (un)simply uncertainty unbridled. But isn’t that also the definition of all creatures? Of Gus? Of (your pup) Bowie? Of us?

I often find myself gravitating toward received form as a way to mete & measure this uncertainty—one can’t stare into the void too long without a tether (or leash!). But Gus has made me truly realize that even the most domesticated of forms—the perfectly constructed Elizabethan sonnet, say—must likewise incorporate surprise, variation, spontaneity. It’s not so much duality as multiplicity. (I’m thinking here of Herrick’s line from “Delight in Disorder”: “I see a wild civility.”)

When Gus first came home with us from the humane society (his third home in six months), I was hell-bent on training him. He was going to be the best-behaved dog in the Mountain West. But he isn’t, not even close—he is a dogged dog, to be sure. And now, I love him for his wild, independent spirit, not in spite of it. I love him for his multiplicity.

"We’re animals too, just as subject to the whims of the world as a puffin, a tulip, a dung beetle."

In your poem “Fetch” that appeared in Birmingham Poetry Review, you write: “Stay, I say, and Sit – / exhibits of my neuroses…”

Does this hint at what you think drives our fear of what’s wild? Or, more specific to this conversation, what drives our need to control both wildness on the page and in our animals?

Many of our neuroses & anxieties, I think, stem directly from this fundamental dissonance. We like to think of ourselves as higher order beings—fully rational, fully civilized, fully in control. But, we’re not. We’re animals too, just as subject to the whims of the world as a puffin, a tulip, a dung beetle.

We’re happy to acknowledge this in abstract discourse, but we’ve done everything possible to hide this fact from ourselves. We use forks & knives & spoons (god forbid we eat a salad with our hands). We’ve invented commodes & bidets (for sanitary and sanity reasons, I’d argue).

For the past year or so, I’ve started to work toward a regular practice of Mindfulness. Which is, of course, exactly what our dogs practice every day. They live in the present. They control what they can. They don’t worry about the rest. What great teachers they could be, if only we were more willing pupils.

Your poems are so drenched in rhyme, slant rhyme, assonance, and consonance. I could pick a number of examples, but let’s go with “Surrender the Animal” because those last few lines won’t come down from my mind:

Me: too rational,

too busy thinking what these people thought

of me, wearing a suit to a funeral

in Nebraska. Maybe regret’s futile.

Still though, I wish I’d screamed my animal

grief like the animal I think I am.

What is the ideal role for sound to play in a poem?

The role sound must play in a poem is exactly that: serious play, playful sincerity. (If you see Gus with his tennis ball, you’ll see—he gets it.)

"We must grieve the living if we’re to appreciate them, if we’re to accept their eventual going."

A follow-up about that poem: you draw on how animals grieve to illuminate human grief. How else have animals informed the way you explore human complexities on the page? Has Gus helped in this regard?

I’m not sure this answers the question, but, being a poet, how could I pass up the opportunity to share some thoughts on mortality.

By comparison, death makes the previously mentioned problems-of-being-human quite minor. (To quote Larkin: “The mind blanks at the glare.”) Think of the pomp & circumstance we ascribe to death—the ornamentation of funeral rites, 21-gun salutes, the Minwax-sheen of the casket itself. We ritualize & aestheticize death out of terror and uncertainty. We make sure the urn is well-wrought.

But this only takes us farther from the grief-work we must do, the excavation. On a farm, death is flat, plain, and part of life. You don’t get used to it, but you accept it. (This time, Harold Bloom, on Keats: the poet’s “gift is one of tragic acceptance.”)

Since Gus has joined our pack, we’ve already begun the process of grieving for him. He’s only two. He’s healthy. He’s impossibly energetic. But we must grieve the living if we’re to appreciate them, if we’re to accept their eventual going.

There’s that age-old adage, perhaps best summarized (for my generation, at least) by Counting Crows: “Don't it always seem to go / That you don't know what you've got ‘til its gone.”

Only in accepting the impending gone can we know what we’ve got.

Your poem “Dog,” which appeared in diode, opens with the epigraph “Let them have dominion” from Genesis 1:26 and uses an uncle’s treatment of a dog as a microcosm of that dominion. Can you talk more about the premise of this poem and what you hope readers take away from it?

The passage from Genesis reads, in full, “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

But why shouldn’t dogs have dominion too? Or any other animal, for that matter? If you ask me, there’s something creepy about this transitive god-complex.

But, again, we’re back to the idea of control and domestication. To me, the poem is about averting my own glance, about taking pleasure in suffering, when I was a child. My uncle, who was once a professor of biology (and who, therefore, unequivocally knew the scientifically-verifiable ‘interrelatedness of all things’), kept dogs chained down by the ponds on my grandparents’ farm. Why he did this, I don’t know.

But this is a phenomenon almost entirely distinct to humans (if we disregard, for the time being, cats and orcas)—the malevolent thrill we find in exerting power over other creatures.

We all know the one about the ants and the boy and the magnifying glass.

Or, to take the Aristotelian route, it’s a poem about the competing desires of egoism and the supererogatory, avarice vs. charity. Or, simply put, self-importance winning out over fundamental goodness. We must care for the world & all its beautiful, beautiful things.

"...there’s something creepy about this transitive god-complex."

A metaphor or simile for Gus?

Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks.

Raena Shirali: When the Looking Hurts

Raena Shirali on her beloved pit Harley, the impetus behind her (must-read) debut book, and why she believes poetry should do the hard work of looking, of validating those who feel unseen.

I'm going to keep this introduction short because goddamn. We are lucky to live in a world with Raena Shirali, and this interview is proof of that. We talk about her beloved pit Harley; how reckoning her identity and history informed themes of survival, race, assimilation, and trauma in her debut book (which you must read); and why she hopes this collection helps readers look "especially when the looking hurts."

A little about Raena: she's the author of GILT (YesYes Books, 2017). Her honors include a 2016 Pushcart Prize, the 2016 Cosmonauts Avenue Poetry Prize, the 2014 Gulf Coast Poetry Prize, & a “Discovery” / Boston Review Poetry Prize in 2013. Raised in Charleston, South Carolina, the Indian American poet currently lives in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where she is the Philip Roth Resident at Bucknell University’s Stadler Center for Poetry, & serves as a poetry reader for Muzzle Magazine. You can read her poems online at Gulf Coast, Ninth Letter, and Tupelo Quarterly.

TW: sexual assault

Tell us a little about your dog Harley. How did he come into your life?

Harley is an incredibly energetic pit mix puppy, though his crazy comes in bouts—right now, he’s curled up next to me on the couch, snoring and apparently dreaming about squirrels.

I imagine origin stories like Harley’s are common, especially because of the stigma that comes with rescuing a pit. About a year ago, I found myself saying to a prospective roommate—without having planned to at all—that I was looking for pet-friendly housing (which was maybe a bit preemptive on my part, considering I had no pets and no pet prospects). Before I even moved in, my soon-to-be-roomie sent me Harley’s info, and I really just could not handle how adorable he was. Fast forward through a winding a series of Facebook posts & meetings with Harley at his foster home, to the adoption event at our local Petco, where Harley was crated on the bottom row (because he is huge) of stacks and stacks of perturbed animals. He had apparently just shredded a comforter out of stress. Bits of stuffing were scattered around his cage, and an event employee—a self-proclaimed “pit expert”—told my partner and I what a huge mistake we might be making by rescuing him, regaling us with tales of pits gone wrong, none of which were about Harley. We very awkwardly paid for and took him home anyway, and I’m happy to report that he has not shredded a comforter to date (R.I.P to the two shoes he’s chewed up, though). Haters gonna hate.

What impact has Harley had on your writing? I know in the thank-you notes for your book Gilt (YesYes Books, 2017), you thank Harley for “making every day possible.” (Oh, my heart!) Other than the general force field of love and support dogs offer, does Harley help make the actual process of writing possible?

Perhaps this has more to do with the nature of my projects, but writing can be extremely traumatic for me. There are certain poems whose generation I find cathartic, but for the most part, my writing either seeks to reconcile aspects of my identity as a woman of color and survivor of sexual assault, or seeks to interrogate cultural and national systems related to the treatment of women. And I love doing that work, but that’s not to say it isn’t painful. Harley really helps me write by helping me not write—by making me look up & around & see something that’s alive & not human & that has, I think, a good soul.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that I have struggled with depression and anorexia in the past, and those struggles are ongoing simply by virtue of my having to be vigilant about, say, feeding myself enough, or making myself get out of bed. Having a 68-pound dog-son to take care of every day means I have to get up. I have to eat. I have to take care of myself in order to take care of him, in order to not be bothered constantly so that I can then have the space to write. As a Virgo, the joy of having a pet has come largely from daily regimen—regimen that necessitates that I be mindful about making space and time for writing, for cooking, for exercise. Especially now that I’m on a writing residency, where every day opens before me like a blank page, caring for Harley is indispensable to caring for my work and myself.

"Harley really helps me write by helping me not write—by making me look up & around & see something that’s alive & not human & that has, I think, a good soul."

Speaking of Gilt, I have to say this book took me by surprise in the best way. It turned out to be everything I wanted to read about grappling with first-gen identity and being a woman of color in America and the added complexities that brings to the romantic realm. How did the vision for this book come about? And what is your hope for this book?