Susannah Nevison: Renaming the Body

I was just reading in The New Yorker "Are Disability Rights and Animal Rights Connected?," a piece that profiles disability and animal rights advocate Sunaura Taylor and her work as a painter and an author – specifically, how her art explores the contentious "space where disability and animality meet."

It's worth a read, and afterwards, my thoughts immediately circled back to this very interview with Susannah Nevison. It's not that Susannah's ideology aligns with Taylor's – I can't speak to that. But like Taylor, Susannah says her work aims to resist typical disability narratives, the ableist inspiration stories and the ones where the body is "fixed" and assimilated. And animals help her tell that story, too.

Before you hear it and meet her beautiful dog Ella May, I want to thank Susannah for her latest book, which you should read immediately. It sticks with you, every poem.

A bit about Susannah Nevison before we dive in: she is the author of Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry. New work can be found in, or is forthcoming from, Crazyhorse, The National Poetry Review, 32 Poems, Pleiades, The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, Guernica, and elsewhere. She is a Clarence Snow Fellow at the University of Utah, where she is a doctoral candidate. For more information and links to her work, you can visit her at www.susannahnevison.com.

Photo: Susannah's dog Ella May, a pit bull mix (possibly basset hound, dachshund, or beagle, says Susannah), wearing an orange bandana with a vest that says, "Adopt Me."

I know you mentioned you don’t know much about Ella May’s backstory other than she was found on a street. If you had to invent one for her, what would it be?

Ella May is named after a fictional character, Ellen May, on the show Justified, based on Elmore Leonard’s Fire in the Hole series. Ellen May is a sex worker. Her character begins as a stereotypical “stripper with a heart of gold,” but she’s quickly shown to be someone much more layered and nuanced. Our dog is similarly complicated, and there’s part of her that is just so unknowable—she is, after all, a dog—so I always wonder what’s really going on inside her head, where she’s been, and what she really thinks of the world.

I like to imagine Ella May as leading an itinerant lifestyle akin to her namesake’s—maybe she was a boxcar dog, riding the rails and taking in the views. I like to imagine she got off the train in downtown Salt Lake, trotted right to our front door, asked for a room, and hasn’t left since.

Do you ever write about Ella May, purposefully or otherwise?

I don’t ever write about her. I talk about her, and to her, all the time. And I write with her—she’s either at my feet, or seated next to me with her chin or a paw on my lap.

Let’s talk a little about your (stunning, otherworldly) collection Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), a book teeming with animals – there are bats and birds and wolves and foals and horses. We begin with “My Father Dreams of Horses,” the first in a series of poems by the same title. In a book that covers thematic ground like myth, surgical trauma, disability, identity, and family history, the horses here seem almost prophetic:

if you wade into the horses—

if flames—if you cannot keep

her from burning—if she will not

keep—if the horses burn—

if your daughter is born—

Can you talk about the horse as a symbol in this collection and perhaps their connection to the medical history referenced throughout?

Many of the poems in Teratology are reimagined encounters with my extensive medical history, and the ways in which that history intersects with my father’s extensive recovery from severe burns. The opening poem you mentioned hits on both these threads—congenital trauma and my father’s fire accident— and I hope the poem serves as legend for the book that follows.

One of the birth defects I was born with is very common: clubfoot. The medical term for it is talipes equinovarus, which roughly describes the foot’s abnormal shape. A clubfoot is turned in at the ankle, and elevated at the heel like a horse’s foot. I am fascinated that we call congenital birth defects teratogenic—from the Greek for monstrous—but we give these so-called monstrous defects names that describe them in desirable and beautiful forms, such as a horse’s foot. Of course, practically speaking, it’s undesirable for a human foot to be horse-like, but the idea that we name the defect after the place in nature where it is useful, where it makes absolute biological sense is so striking to me. I wanted to use the clinical language of my diagnoses to refigure the disabled body. What might it look like, for example, if the disabled body—at least symbolically— possesses all the strength and wildness of the language we attach to it? What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative— medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself? What if the father figure, himself a trauma survivor, imagines his future child’s disabilities in that shared language?

"What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative—medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself?"

Photo: Ariel view of Ella May lying down, looking up at the camera, one ear pinned back and one pointed skyward.

In “Bestiary,” you write, “You walked / into the wolf’s mouth and you were lost: / as in all good stories, they claimed / you for their own.” So much of this collection is about who lays claim to the speaker’s body. Can you talk more about this guiding question?

Bodies are complicated. Disabled bodies are especially so, since they are always in some way at war with themselves or their environment. As someone who started having surgery when I was five-months-old, I’m the product of extensive medical intervention—I am, quite literally, shaped by surgeons’ hands. In many ways, this is an enormous gift, because I’ve been able to engage with my environment in ways that seemed impossible at first (I wasn’t expected to ever walk, let alone lead the active childhood I eventually did), and I’m incredibly grateful for all the experiences that surgery has given me access to.

But that access—as granted by medical intervention—does have a cost. Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me. I’ve only known my body as it was made and refashioned by medicine, and as it resisted those procedures. It’s a strange kind of grief: knowing that your body isn’t made for the world you live in, or the life you want to have. But there’s also a strange kind of joy in knowing that you can, quite literally, be remade and reborn, although it doesn’t negate the shame or guilt that comes with living in a body that won’t “behave.” Writing Teratology became about reconciling my gratitude and awe for—and my dependence on—medical intervention with my accompanying grief, shame, and dissociation that comes with inhabiting a body that never feels like it’s mine alone, and one that others deem deviant or wrong.

"Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me."

Photo: Close up of Ella May sleeping on a purple blanket, one paw next to her face, books on bookshelf in the background.

Let’s take a look at “Lore,” a poem that draws an explicit connection between the speaker and an animal, in this case a stillborn foal:

…isn’t this the way

I was born, the wide dark trembling, a swell

of blood pounding across distance,

forcing inlets between bone?

They say I was tied like a calf,

legs knotted for stumble. They say

I was a strange, mute animal.

It seems to me that the animals in this poem and throughout the collection help illustrate ableist world views and their othering, destructive effect. How do you think these poems engage with that history and present?

I really wanted Teratology to resist typical disability narratives—ones wherein a body is diagnosed, fixed, and then happily at home in the world, or ones where the disabled body is tragic, a mirror for what scares or threatens the able-bodied world. To do that, I tried to give the disabled body the literal wildness of its clinical diagnoses, to let the disabled body kick and keen and rage against the constraints imposed upon it, medical or otherwise. So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies. Many of the poems in the book became an exercise in reinventing and refiguring spaces through the disabled gaze, while the disabled body undergoes its own encounter with the medical gaze. I wanted the disabled body, while undergoing medical intervention, to unleash its wildness in these spaces, to reinvent the world around it, even as it undergoes its own kind of reinvention.

"So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies."

Photo: Ella May sitting down and giving some serious side eye, wearing a green bowtie collar.

In poems like “Pre-Op Portrait with a Colony of Bats,” we see glimpses where the wild meets the man-made world:

They held the mask

over your mouth, pumped you

full of forgetting: the sky

fashioned a noose and hanged

herself, purpling and gasping—

Several poems in the collection deal with this fog of forgetting – through anesthesia, morphine – and the way this space blurs the boundaries of the lived-in world. Can you discuss this psychological space and why it’s rich landscape for exploring the body and self?

So many transformative moments happened while I was under anesthesia, and so it’s impossible for me to have any memory or recollection of these key moments in my personal history. The closest I can get is through my own medical records. That momentary space between consciousness and induced unconsciousness is, for me, one of my earliest memories. Most people, I imagine, have specific moments or events they recall as their earliest memory—instead, I have this weird non-event, this kind of fading away. I don’t have access to any moment of witness, but I do have access to the memory of losing that kind of control and autonomy. The act of witnessing, in this collection, had to take place then in the moments before and after surgical intervention—the interstitial spaces, as it were— and for me that became an essential part of disrupting the expected surgical narrative. I had to circle the large surgical events because I was, in terms of memory, absent from them.

You said in an interview with The Cloudy House, “I’ve always been trying to make sense of what it means to live in a body that is constantly undergoing revision—and how physical transformation changes not only one’s relationship to the world, but to family and identity.” Did writing these poems change your relationship with your body in some way? I read the final poem “If You Come to the Sea and You Must Cross” as ars poetica: “When the good work is done / you begin.”

Writing these poems gave me control over a narrative I can’t ever know completely, and in that sense, changed the way I think about my body. If I can’t know my history completely, I can at least invent and shape a narrative that feels the most true to my experience of the world and my body in the world. I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention. The last poem is very much an ars poetica, but it’s also an homage to the disabled body’s ability to reinvent and reshape itself.

"I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention."

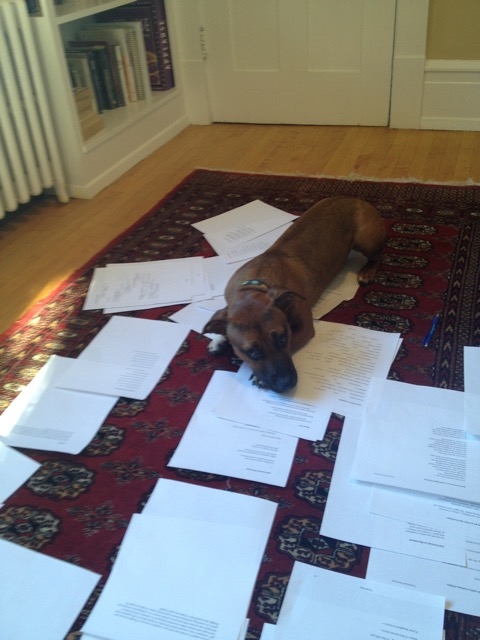

Photo: Ella May lying on top of printed poems laid out on the carpet, possibly helping her human with the editing process.

Was this a difficult collection for you to write, and if so, did Ella May’s companionship help you forward?

Yes, the collection was pretty difficult to write because so much of the material is emotionally fraught for me. This book was mostly written between dogs—we had to euthanize our previous pup in February 2012, the winter before we moved to Utah. We adopted Ella May in late May 2013. She couldn’t have come into our lives at a better time. I had just finished my first year of a PhD program, and was finally beginning to figure out how to make Utah, and the manuscript in progress, work. She was great company for the final stages of writing and ordering the manuscript. She helpfully stretched out across the pages on the floor, got dog hair everywhere, and rolled around on the floor noisily while I attempted drafts of the final poems. She’s a wonderful lounger and napper—something I also pride myself on—so she also snored loudly while I wrote. (I’m sure that helped keep my expectations for the book in check.)

A metaphor or simile for Ella May?

The best potato west of the Mississippi. A mismatched slot machine. The sweetest warthog you’ll ever meet. Everyone’s favorite, klutzy waitress.