Allison Titus: What Resilience Is

Poet Allison Titus on fostering pugs, veganism, and writing with conviction.

Friends, I'm honored to share this conversation with Allison Titus in loving memory of her pug Elly who died shortly after we started this interview. Allison's devotion to her dogs and animals is palpable both in her life and in her poetry. I don't say this lightly: she is a force of love and goodness.

A little about Allison: she is the author of three chapbooks: Instructions from the Narwhal, Topography of Tears, and the forthcoming Sob Story; two books of poems: Sum of every lost ship, The True Book of Animal Homes; and a novel, The Arsonist’s Song Has Nothing to Do with Fire. She is the recipient of an NEA literature fellowship, and her poems have appeared in A Public Space, Tin House, Boston Review, Blackbird, and Typo, among other journals. A proofreader / copy editor by day, she also teaches in the low-residency MFA program at New England College. Along with the poet Ashley Capps, she is editing an anthology called The New Sent(i)ence which explores the creative agency of non-human animals in 21st-century poetry.

Before we talk about your pugs Eleanor (Elly) and Daisy, can you tell us a little about your background with fostering and rescuing pugs? What made you start, and how has it affected you?

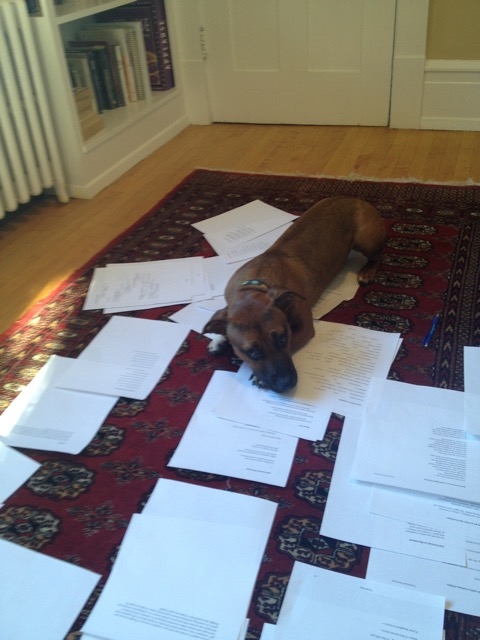

Ruben, the pug who inspired Allison to start rescuing.

I started fostering pugs because I adopted Ruben, a pug who came from a goat farm. Pugs are weird! They are ancient foot warmers, and all they want is to lounge. This is the dog that is after my own heart: we are lazy, and we like to sprawl. When I discovered that there was a Mid-Atlantic Pug Rescue, I volunteered because I figured, if all it took for a dog to get a new permanent home was a temporary stay with me, or something as simple as a transport need, at the very least I could provide those things. The endless population of stray and homeless dogs—I mean all homeless animals, but dogs have wedged themselves the deepest in my life—is one systemic problem (of many!) that breaks my heart on a daily (hourly) basis. I also believe very strongly in adopting animals rather than buying them, while understanding that a person might want a particular breed of dog for a variety of legitimate reasons, and that’s where rescue groups dedicated to certain breeds come in: they remove a fraction of animals from already over-populated shelters and offer an alternative to purchasing a purebred dog from a breeder or pet store.

You mentioned Elly and Daisy helped you through some difficult times, something I can really relate to. I feel like I’m always trying to explain why dog companionship is such soul salve, and I’m curious about your take.

It’s so hard to explain to someone who doesn’t already get it, isn’t it? And if you get it, you get it, absolutely. There was a period of time, of about three years, when I moved from apartment to apartment by myself with Elly and Daisy. At that point, I’d never lived alone, and I had one understanding of what home was—the house I had lived in for 14 years when I was married. And so all of a sudden, the only thing that made me understand what home was became: wherever Elly and Daisy were. Even if it was a temporary place, as long as those guys were with me, we were OK/we were home.

I guess that was the first time in my life that I really understood “home” as a concept that could be embodied emotionally rather than as something that was primarily represented as a physical place. And they were just such great companions during a time in my life when I was the saddest and the loneliest: I don’t know what I would have done without them; they made the hours bearable and hilarious. Also they taught me what resilience is.

Daisy and Elly

"They taught me what resilience is."

As you may have gathered from my fangirling on social media, your latest book The True Book of Animal Homes (Saturnalia, 2017) absolutely floored me. (I read the entire collection out loud to my husband because I needed to talk about it with someone immediately.) It has such a concrete and expansive vision of its world. For those who haven’t read it yet, it’s divided into three sections: the office poems, the animal homes poem, and the essay poems. I love how the collection uses habitat as a way to emphasize how close the human and animal worlds are, all the overlap. How did the arc of this book take shape for you?

Piper

Oh my gosh: thank you! That is actually the most amazing compliment I think I’ve ever been given: that you would have read my poems aloud. I am so lucky my book found you and your heart.

The book took shape over several long years, and the office poems were written first. I spent a lot of my post-grad years working temp jobs that were pretty corporate, and I was extremely out of my element in those environments. I am basically always disheveled. I spent eight hours a day feeling like an alien, and at some point, I had to make those days into something that felt worthwhile, that wasn’t just lost beige time, or I would have died. OK, that’s dramatic, but I would have gone crazy.

So I started writing poems about real and invented offices. I thought a lot about the spaces and stations I occupied in those roles, physically and philosophically. And then as the years went on, I started writing more overtly about animals, and it was just such a natural overlap, to combine those two impulses, considering the space and stations humans and non-human animals are relegated to. We’re all just roaming around the same planet, trying to stay alive, hoping to match our desires with whatever kindred external force is compatible and game. And then the final gesture, the essay poems—naming them “essays” allowed them to exist for me in a space that felt more...sanctioned to hold a stance but not subvert or sacrifice the craft of the poem. I wanted those poems to do what essays aim to do: try to establish an argument by exploring an idea or a series of ideas that accumulate to some larger question or inquiry.

"We’re all just roaming around the same planet, trying to stay alive, hoping to match our desires with whatever kindred external force is compatible and game."

I see the offices in the first section as a symbol of both the human disconnect from and intersection with animal world. How our fates are yoked to the fate of animals. Has caring for your dogs contributed to this outlook in your poems?

I think living with dogs for my whole life, and being the kind of person who considers my dogs to absolutely be family, and being aware that not everyone feels that way, and that not everyone has had a bonded relationship with an animal, and that actually so many animals suffer such terrible abuse and neglect at the hand of humans…I think my awareness of that disparity and disconnect, and my awareness of the extreme variability in our human experience with non-human animals informs the poems, and the book in general.

I can’t help reading animal rights philosophy into a lot of these poems, but especially “The True Book of Animal Homes,” which you noted is dedicated to your rescue pugs:

Some are sold by the road like jam like chairs like bonnets

What’s invisible

the cages or the shreds or the barns,

how their callused bellies drag

whelp-heavy & freckled

And this incredible line, too: “Here they come, the mongrel ghosts of my heart.”

And this from “Essay on Economies of Scale”:

This morning on the kill floor

the piglet tried to nuzzle the worker Like a puppy,

the worker says, It happens all the time.

How did your veganism help inform this collection? And what were the specific challenges of writing about a subject both so personal and (usually) divisive?

I became vegan in 2009, and I think as I became more informed about veganism and about animal rights initiatives, the lifestyle became more political for me than I expected it to. And it just grew harder to avoid having that fundamental layer of my life not become a texture in my poems—basically, veganism is my one conviction; I have no religion, have never had a religion. I believe in kindness and in generosity and in doing no harm. I want to try to get close to what I feel are the essential things, in my poems, but I don’t want to just write polemics that sacrifice artfulness for pronouncement. I care too much about poems to not worry that there’s a tricky balance to strike between idea and image and experience. More than I care about creating anything defined, I want to create something felt.

"More than I care about creating anything defined, I want to create something felt."

I want to talk about “Essay on the New Year,” namely that ending:

Who’s to say

how we go on or don’t

go on, despairing

unspecifically.

That thy misery be

known for what it is:

vernacular, of

an interior sea.

I think this is a good reminder that despair can be neutral, that it doesn’t need to be cured, that maybe what we need is a better language for our inner worlds. Can you talk about what prompted this poem?

Honestly, it was written so many years ago, I don’t remember what the exact impetus was, beyond creating a specific texture and intensity: but yes, it seems at some point, maybe the desire is not to repress the darkness, but to embrace it. Life is hard and sad and strange, and also miraculous: why pretend it’s anything else?

Which is more necessary to you right now: poems about grief or poems about joy?

For now: poems about grief.

A metaphor or simile for Elly and Daisy?

Well, Elly is (was—she passed away in July) my shadow. Daisy … is the Fear of Missing Out, embodied. Also, Daisy came with her name. She would be the perfect Betty.

Gretchen Marquette: The Last Time We Were Strangers

Poet Gretchen Marquette on her life-making relationship with her dog Lucy, the creative process, Rumi's love dogs, and what animals have taught her about vulnerability.

I'll keep this short because I want you to experience Gretchen Marquette’s love stories about her dog Lucy and her insight on the creative process right now. But I will say, if you haven't checked out her first book May Day yet, do it. It sticks with you.

About Gretchen: Her work has been featured in Poetry Magazine, The Paris Review, Tin House, Harper’s, The Literary Review, PBS NewsHour, and other places. Her first book, May Day, was released in 2016 from Graywolf Press. She lives and works in Minneapolis.

Tell us about Lucy and your 14 years of companionship with her. Some favorite moments, memories?

I brought Lucy home on Mother’s Day in 2003. Lucy (then named Minnie) had been living at a shelter for six months, and was a little over a year old. I’d gone to the Humane Society with a friend to see if they had any rabbits, but while we were there, he convinced me to look at the dogs, and the second I saw her, I knew she was mine. I visited her several times, and went through the long application process they required, but eventually I was there handing a green leash over to the woman behind the counter. She said, “This morning I told Minnie that she’s finally going to her forever home.”

Now that I’ve written that, it sounds saccharine, but it wasn’t. Lucy had shown up there in pain and a little underweight, and watched her littermate be adopted and disappear three days into her own six month stay. She arrived knowing no commands, and with an infection in her leg so bad she couldn’t step on it. She wasn’t spayed, and didn’t know her own name. I didn’t know it yet, but here was a dog that wanted to be touched all the time, and she had gone so long without any consistent affection. And all of that was over for her. She did have a home.

There have been dark times in my life, but rescuing Lucy and giving her the love she wanted is one thing I know I’ve done right, and one reason I’ve been glad I was alive to help her. We’re getting into an It’s a Wonderful Life moment here, which is the opposite of trying to prove all this isn’t saccharine, so I’m going to stop there.

When I took Lucy outside of the shelter, she was too afraid to get in the car. It turned out she was afraid of everything. While we stood there, a strong wind blew, and she cowered in the grass and peed. It had been so long since she’d been outside, and her entire puppyhood had been spent in a small outdoor kennel. I knew I had to lift her in the car, but I was afraid, too. Would she bite me? It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since.

It’s hard to pick the stories I want to tell about my life with Lucy – I could write pages and pages, and this is especially true because until July of 2014, there was another dog with us – my husky, Sage. Sage and Lucy were not very close most of the time, but were partners in crime when it came to getting in trouble – running away in particular.

Once, I got a phone call from an unknown number. It turned out that someone had left the gate open at the house I was renting, and my dogs had gotten out. Lucy is a Treeing Walker Coonhound, but when the woman said, “I have your beagle I think?” I knew it was Lucy. “My husband is trying to catch your husky,” she said. I was two hours away, so I told the woman my address and asked if she would put the dogs inside (I left my doors unlocked in those days), and she said, “Honey, these dogs have been down to the river rolling in dead carp and they are covered in it.” When I showed up at home, I saw for myself. It was the foulest thing I could imagine, but they were both so happy. Still, it was a night of a thousand baths.

Lucy has always been a good friend to me; she’s very tuned in. One night, I woke in the worst pain I had ever felt. I would have a root canal later that day, but when I woke, I didn’t know what was going on, and it was 3 a.m., and I was afraid. My boyfriend told me to relax and not get upset because it would make it worse, and then went back to sleep, but Lucy sat up with me for hours while I cried on the living room floor. At one point she came and sat right in front of me, and I put my arms around her and cried into her neck, and she sat there and let me do that for as long as I needed. It was a profound experience of being loved and comforted – it’s for that reason that of all the thousands of days I’ve spent with my dog, this is one I choose to tell you about.

"It almost makes me cry, remembering this, because it was the last time she and I were strangers to one another. That night she slept in my bed after a lifetime on a concrete floor. She’s slept beside me every night since."

In your book May Day’s dedication and in your interview with Kaveh Akbar on Divedapper, we can see that you value your friendships: “I don’t think I’d be here if it wasn’t for those friendships. Which is strange because we give such a privileged place for romantic love and familial love, but in both of those forms of love you are under a contract in some way. But then you have friendships, which have actually been some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had in my life.” Do you count Lucy among these life-saving relationships? Or do you consider that relationship more familial? I’m always curious about how folks think about their relationship with their pets.

My relationship with Lucy is definitely a life-making/life-saving one. She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman. I realized recently that I’ve spent more time with her than I have with my siblings.

One thing I hate is getting in the car for a long drive home alone. Especially at night, but really any time. Having Lucy in the back seat makes it suck less. She’s lived in three states with me, and at nine different addresses. She was there when my brother deployed (twice) and when my partner left (also, unfortunately, twice) and she was there when my niece came home from the hospital and when I came home after signing the contract for my first book. I know she hasn’t “shared” in these moments in the way a human being could have, but she accompanied me through them in a deep way and I’m grateful.

"She has steadily accompanied me through my adult life in a way no other creature has, human or nonhuman."

I love that your dogs show up in your first poetry collection May Day (Graywolf Press, 2016), like in the poem “Powderhorn, after the Storm.” This part is one I think most people with dogs can relate to (maybe too well – I winced remembering times I had lost my temper with my now-dead dog Pete; I think that regret will follow me a lifetime):

I jerked her leash, nudged

her through the door

with my knee. These cruelties

aren’t held against me.

I regret them deeply.

What is it about documenting regret in a poem that appeals most to you?

Sage

I suppose I felt like it was important to be honest about that night, and losing my temper with Sage was part of it. I didn’t know it until I had time to process it later, but I was irrationally angry at her that she was sick, and I knew that she wouldn’t be with me much longer. I was terrified to think of losing her. I’d raised her from a six-week-old; she’d been in my life since I was nineteen.

I had also just had a terrible, frightening day, and I wanted so much to be asleep. She’d woken me up, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to fall back asleep. The power was out everywhere and it was hot, and there were constant sirens. I still regret it. Sage was such a good dog. She deserved so much better that night. Letting myself off the hook in that poem would have ruined it.

So much of May Day is in conversation with the interiors grief creates (to quote one of many examples, in “About Suffering”: “there are so many / places for grief to live that we can’t note each address”). These poems trace the ending of a romantic relationship, the worry over your brother who was deployed to Iraq. And it seems that animals are a language for grief in this collection – the deer wandering through these poems (which we’ll talk more about in a bit), the macaw and painted turtle, the cardinals in the poem “Red.” Can you talk a bit about how animals helped you excavate this rawness, this vulnerability in your work?

I lived outside of a small town in a wooded area, and there were animals everywhere. There would be hoofprints in the sandbox some mornings, and the railroad tie retaining wall behind our house was full of toads. There were skunks, and raccoons, chipmunks and squirrels – I saw them every day. Sometimes terrible things happened to these animals. They got sick and died. They killed each other. They were hit by cars. I don’t remember processing any of this, but my dad told me that when I was two, I would remind him, every time he drove away from the house, not to “bump the deers.” So their well-being was an early concern. They were vulnerability personified.

I also think (and this might have to do with my deer imagery issue as well) that watching a deer skinned and dressed in my neighbor’s yard when I was small was shocking and transformative in a huge way for me. For one thing, it changed how I thought about bodies, including my own.

I have used this quotation many times in connection with stories about what might have led me toward poetry, but it has never stopped feeling right to me. Alan Williamson says that, “for many of us, the moment when we experienced something we could not share with our outer world, because our outer world had given us no 'word' to acknowledge it, was the moment that impelled us toward poetry. And poetry was a struggle with the given language, to make it give us better words than 'unlikely' for what had fallen out of this world’s likelihood.” I think that’s the truest statement I’ve ever read, and my earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals.

"My earliest transformative experiences that fell out of the world’s likelihood – stories that taught me about life and death – were told by animals."

True or false: To love is to grieve in slow motion.

False. I feel they are separate. I’ve actually spent a lot of time thinking about this! I prefer to think of grief as being powerless to negate or eliminate beauty or joy, and I’ve also accepted (more or less) that beauty can’t eliminate grief. Grief is not going anywhere – there’s always more to come. But there’s a good insurance policy in that. If grief and joy can’t touch each other, joy is protected, and there will always be more of that, too.

Lucy is going to be sixteen years old in December. In August, they thought she had a mass in her bladder, and for a few weeks I was wiped out with sadness and worry. It turned out that wasn’t true, and now she’s healthy again. But I know she can’t stay forever. Every day, I cook ground beef and mix it with pureed pumpkin and mix it with her dog chow, to help keep her weight up. Every day it makes me happy to watch her eat. She wags her tail the entire time.

When I was reading May Day, I started noting in the margins “Gretchen’s deer” whenever one popped up. Let’s look at “Deer Suite” in particular, where the deer is directly tied to the theme of want that drives so much of this collection:

If I say my longing is a doe,

that it bounds,

that it chokes, has parts that splinter,

that it can be split

from breastbone to pelvis.

(I love how seamlessly this connects to the epigraph in “Doe,” a poem that appears earlier in the collection: “A Wounded Deer—leaps highest—” from Emily Dickinson.) Let’s talk about longing and want and when you first realized that theme would shape this book.

I think that theme has shaped everything I’ve ever written and will continue to do so. About a third of the poems in May Day were taken from my thesis. At the time I was really interested in those lines of Rumi’s – “There are love dogs / no one knows the name of. // Kill yourself / to be one of them.” I heard another poet use them once in the spirit of romantic adventure and they rang a little false to me. I don’t think we all get to be love dogs.

The poems I was writing during graduate school were about the partner I was in love with, and about Lorca, and about my little brother who is a soldier. They were about my own broken heart. I wondered if we were all love dogs, and if the condition of being one comes and goes, or if it really is a choice, as the poet I mentioned above seemed to think it was. I still don’t know. But this idea of longing plays into that directly.

During graduate school I wrote a poem called “Love Dog” (and, in fact, that was the title of the manuscript I first turned over to Jeff Shotts). The poem was about the first dog I ever met who was afraid of me and didn’t want to be touched. It was the dog that belonged with the family who bought our house in the woods. I had reached out to pet the dog and she growled at me. Her boy held her collar and apologized, and then said, “Some people hurt her for fun,” and then told me that she had been a stray, and that someone had shot her with BBs and they were still under her fur when they found her, running loose.

I realized there was nothing I could do to prove myself to this dog, and I saw myself for the first time as an unknown quantity to another creature. That I had the capacity to hurt someone else. She didn’t get to be a love dog. Things have happened in my life that have made it harder for me to be one, too. Is that a failure of courage or character? I don’t know.

Even though this seems to be getting off topic, I don’t really think it is. I want to be a love dog. I long to be one. And sometimes I feel like I am killing myself to be. But what I really wish is that I could be a love dog and also not kill myself.

"I don’t think we all get to be love dogs."

What are you absolutely obsessed with right now? It can be anything, not necessarily poetry or animal related.

I’m obsessed with cave paintings, with the spacetime continuum, with images of The Madonna, and with origins of human mythology and our earliest attempts at situating ourselves in the world. (I’ve been reading Joseph Campbell.)

What’s changed the most for you since your first book came out?

I suppose that it’s been an adjustment to realize, after so many years, that my poems have an audience. For so long it was just my classmates and my teachers. I’ve met new people because of my book; it’s brought friends and opportunities into my life. In some cases, it gave me a deeper home in poetry, and a chance to connect with other poets I deeply admire – some new to their audiences like I am, and others who have been heroes a long time.

Advice for poets staring wildly at the expectation of a second book and coming up short?

I’m working on my second book, too. Some days I feel like I have an answer for you, and some days I want you to tell me what others have to say on the subject!

I know that for me, the process is different than it was when I was writing May Day. I’m much farther removed from my academic community, and I’m working differently because my life as a poet has changed (see above). When I’m writing a poem I have to remind myself that each one deserves its own space. Every poem won’t make it into the book; I have to let the poems arrive, whatever they’re about and whatever form they want to take. That said, it is fun to watch a book arrive slowly – to see themes and motifs materialize. It helps me understand myself and the life I’m living.

I would say trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something.

It’s also a good time to rest, especially if your book just came out. I like intentionally taking time away from writing and using that time for reading. Collections of poetry are always inspiring, but nonfiction books also bring a lot to the surface for me. I just work hard in my writer’s notebook–taking notes, jotting down ideas or lines, etc. During my writing vacations, either what I read will inspire me, or the obstinate part of my brain that’s been told it can’t write for ten days will suddenly find itself very active. It works most of the time.

"Trust yourself the way you used to when you were writing a poem, back before book one. Your new poems can still come into the world the way those poems did, one at a time, and eventually you’ll have something."

A metaphor or simile for Lucy?

Lucy is my home.

Susannah Nevison: Renaming the Body

Poet Susannah Nevison on her pup Ella May, how her poems aim to resist typical disability narratives, and how animals help her tell that story.

I was just reading in The New Yorker "Are Disability Rights and Animal Rights Connected?," a piece that profiles disability and animal rights advocate Sunaura Taylor and her work as a painter and an author – specifically, how her art explores the contentious "space where disability and animality meet."

It's worth a read, and afterwards, my thoughts immediately circled back to this very interview with Susannah Nevison. It's not that Susannah's ideology aligns with Taylor's – I can't speak to that. But like Taylor, Susannah says her work aims to resist typical disability narratives, the ableist inspiration stories and the ones where the body is "fixed" and assimilated. And animals help her tell that story, too.

Before you hear it and meet her beautiful dog Ella May, I want to thank Susannah for her latest book, which you should read immediately. It sticks with you, every poem.

A bit about Susannah Nevison before we dive in: she is the author of Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry. New work can be found in, or is forthcoming from, Crazyhorse, The National Poetry Review, 32 Poems, Pleiades, The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, Guernica, and elsewhere. She is a Clarence Snow Fellow at the University of Utah, where she is a doctoral candidate. For more information and links to her work, you can visit her at www.susannahnevison.com.

Photo: Susannah's dog Ella May, a pit bull mix (possibly basset hound, dachshund, or beagle, says Susannah), wearing an orange bandana with a vest that says, "Adopt Me."

I know you mentioned you don’t know much about Ella May’s backstory other than she was found on a street. If you had to invent one for her, what would it be?

Ella May is named after a fictional character, Ellen May, on the show Justified, based on Elmore Leonard’s Fire in the Hole series. Ellen May is a sex worker. Her character begins as a stereotypical “stripper with a heart of gold,” but she’s quickly shown to be someone much more layered and nuanced. Our dog is similarly complicated, and there’s part of her that is just so unknowable—she is, after all, a dog—so I always wonder what’s really going on inside her head, where she’s been, and what she really thinks of the world.

I like to imagine Ella May as leading an itinerant lifestyle akin to her namesake’s—maybe she was a boxcar dog, riding the rails and taking in the views. I like to imagine she got off the train in downtown Salt Lake, trotted right to our front door, asked for a room, and hasn’t left since.

Do you ever write about Ella May, purposefully or otherwise?

I don’t ever write about her. I talk about her, and to her, all the time. And I write with her—she’s either at my feet, or seated next to me with her chin or a paw on my lap.

Let’s talk a little about your (stunning, otherworldly) collection Teratology (Persea Books, 2015), a book teeming with animals – there are bats and birds and wolves and foals and horses. We begin with “My Father Dreams of Horses,” the first in a series of poems by the same title. In a book that covers thematic ground like myth, surgical trauma, disability, identity, and family history, the horses here seem almost prophetic:

if you wade into the horses—

if flames—if you cannot keep

her from burning—if she will not

keep—if the horses burn—

if your daughter is born—

Can you talk about the horse as a symbol in this collection and perhaps their connection to the medical history referenced throughout?

Many of the poems in Teratology are reimagined encounters with my extensive medical history, and the ways in which that history intersects with my father’s extensive recovery from severe burns. The opening poem you mentioned hits on both these threads—congenital trauma and my father’s fire accident— and I hope the poem serves as legend for the book that follows.

One of the birth defects I was born with is very common: clubfoot. The medical term for it is talipes equinovarus, which roughly describes the foot’s abnormal shape. A clubfoot is turned in at the ankle, and elevated at the heel like a horse’s foot. I am fascinated that we call congenital birth defects teratogenic—from the Greek for monstrous—but we give these so-called monstrous defects names that describe them in desirable and beautiful forms, such as a horse’s foot. Of course, practically speaking, it’s undesirable for a human foot to be horse-like, but the idea that we name the defect after the place in nature where it is useful, where it makes absolute biological sense is so striking to me. I wanted to use the clinical language of my diagnoses to refigure the disabled body. What might it look like, for example, if the disabled body—at least symbolically— possesses all the strength and wildness of the language we attach to it? What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative— medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself? What if the father figure, himself a trauma survivor, imagines his future child’s disabilities in that shared language?

"What happens if we resist the typical disability narrative—medical intervention, assimilation—and instead create a narrative where the language of diagnoses is breeding ground for the disabled body to reinvent and rename itself?"

Photo: Ariel view of Ella May lying down, looking up at the camera, one ear pinned back and one pointed skyward.

In “Bestiary,” you write, “You walked / into the wolf’s mouth and you were lost: / as in all good stories, they claimed / you for their own.” So much of this collection is about who lays claim to the speaker’s body. Can you talk more about this guiding question?

Bodies are complicated. Disabled bodies are especially so, since they are always in some way at war with themselves or their environment. As someone who started having surgery when I was five-months-old, I’m the product of extensive medical intervention—I am, quite literally, shaped by surgeons’ hands. In many ways, this is an enormous gift, because I’ve been able to engage with my environment in ways that seemed impossible at first (I wasn’t expected to ever walk, let alone lead the active childhood I eventually did), and I’m incredibly grateful for all the experiences that surgery has given me access to.

But that access—as granted by medical intervention—does have a cost. Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me. I’ve only known my body as it was made and refashioned by medicine, and as it resisted those procedures. It’s a strange kind of grief: knowing that your body isn’t made for the world you live in, or the life you want to have. But there’s also a strange kind of joy in knowing that you can, quite literally, be remade and reborn, although it doesn’t negate the shame or guilt that comes with living in a body that won’t “behave.” Writing Teratology became about reconciling my gratitude and awe for—and my dependence on—medical intervention with my accompanying grief, shame, and dissociation that comes with inhabiting a body that never feels like it’s mine alone, and one that others deem deviant or wrong.

"Even though I can do most able-bodied activities, I know the only reason I can is because someone else made it possible by literally laying claim to my body, intervening and remaking me."

Photo: Close up of Ella May sleeping on a purple blanket, one paw next to her face, books on bookshelf in the background.

Let’s take a look at “Lore,” a poem that draws an explicit connection between the speaker and an animal, in this case a stillborn foal:

…isn’t this the way

I was born, the wide dark trembling, a swell

of blood pounding across distance,

forcing inlets between bone?

They say I was tied like a calf,

legs knotted for stumble. They say

I was a strange, mute animal.

It seems to me that the animals in this poem and throughout the collection help illustrate ableist world views and their othering, destructive effect. How do you think these poems engage with that history and present?

I really wanted Teratology to resist typical disability narratives—ones wherein a body is diagnosed, fixed, and then happily at home in the world, or ones where the disabled body is tragic, a mirror for what scares or threatens the able-bodied world. To do that, I tried to give the disabled body the literal wildness of its clinical diagnoses, to let the disabled body kick and keen and rage against the constraints imposed upon it, medical or otherwise. So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies. Many of the poems in the book became an exercise in reinventing and refiguring spaces through the disabled gaze, while the disabled body undergoes its own encounter with the medical gaze. I wanted the disabled body, while undergoing medical intervention, to unleash its wildness in these spaces, to reinvent the world around it, even as it undergoes its own kind of reinvention.

"So much of how our culture treats disability depends on ensuring that bodies adhere to certain kinds of protocols in terms of how they look and move, instead of simply expanding or refiguring both environmental and linguistic spaces to make room for these bodies."

Photo: Ella May sitting down and giving some serious side eye, wearing a green bowtie collar.

In poems like “Pre-Op Portrait with a Colony of Bats,” we see glimpses where the wild meets the man-made world:

They held the mask

over your mouth, pumped you

full of forgetting: the sky

fashioned a noose and hanged

herself, purpling and gasping—

Several poems in the collection deal with this fog of forgetting – through anesthesia, morphine – and the way this space blurs the boundaries of the lived-in world. Can you discuss this psychological space and why it’s rich landscape for exploring the body and self?

So many transformative moments happened while I was under anesthesia, and so it’s impossible for me to have any memory or recollection of these key moments in my personal history. The closest I can get is through my own medical records. That momentary space between consciousness and induced unconsciousness is, for me, one of my earliest memories. Most people, I imagine, have specific moments or events they recall as their earliest memory—instead, I have this weird non-event, this kind of fading away. I don’t have access to any moment of witness, but I do have access to the memory of losing that kind of control and autonomy. The act of witnessing, in this collection, had to take place then in the moments before and after surgical intervention—the interstitial spaces, as it were— and for me that became an essential part of disrupting the expected surgical narrative. I had to circle the large surgical events because I was, in terms of memory, absent from them.

You said in an interview with The Cloudy House, “I’ve always been trying to make sense of what it means to live in a body that is constantly undergoing revision—and how physical transformation changes not only one’s relationship to the world, but to family and identity.” Did writing these poems change your relationship with your body in some way? I read the final poem “If You Come to the Sea and You Must Cross” as ars poetica: “When the good work is done / you begin.”

Writing these poems gave me control over a narrative I can’t ever know completely, and in that sense, changed the way I think about my body. If I can’t know my history completely, I can at least invent and shape a narrative that feels the most true to my experience of the world and my body in the world. I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention. The last poem is very much an ars poetica, but it’s also an homage to the disabled body’s ability to reinvent and reshape itself.

"I do think of the disabled body as akin to poetry in many ways: both are made objects, and demand a near-surgical attention to movement, sound, appearance, nuance, detail. Both demand that you see and experience the world differently, with a special kind of attention."

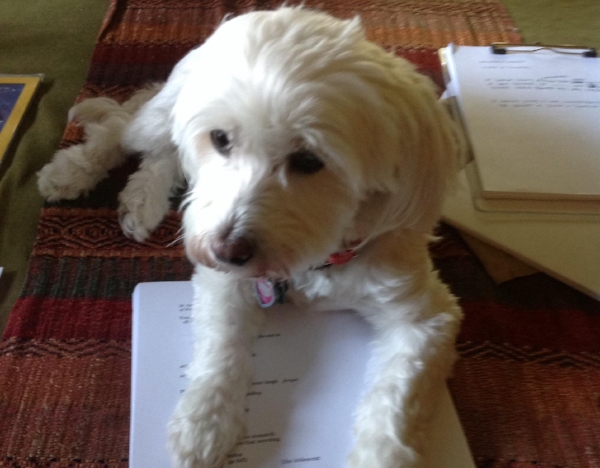

Photo: Ella May lying on top of printed poems laid out on the carpet, possibly helping her human with the editing process.

Was this a difficult collection for you to write, and if so, did Ella May’s companionship help you forward?

Yes, the collection was pretty difficult to write because so much of the material is emotionally fraught for me. This book was mostly written between dogs—we had to euthanize our previous pup in February 2012, the winter before we moved to Utah. We adopted Ella May in late May 2013. She couldn’t have come into our lives at a better time. I had just finished my first year of a PhD program, and was finally beginning to figure out how to make Utah, and the manuscript in progress, work. She was great company for the final stages of writing and ordering the manuscript. She helpfully stretched out across the pages on the floor, got dog hair everywhere, and rolled around on the floor noisily while I attempted drafts of the final poems. She’s a wonderful lounger and napper—something I also pride myself on—so she also snored loudly while I wrote. (I’m sure that helped keep my expectations for the book in check.)

A metaphor or simile for Ella May?

The best potato west of the Mississippi. A mismatched slot machine. The sweetest warthog you’ll ever meet. Everyone’s favorite, klutzy waitress.

J.P. Grasser: Wildness & The Indescribable Realm

Poet J.P. Grasser on his dog Gus: "When I’ve lost myself to the pure pleasure of writing, Gus happily reminds me of all the multitudinous joy & pain & love & suffering going on, at that very minute, in the space outside the margins."

I once told J.P. Grasser that I wanted to live in his brain for a day, and I stand by that. You're about to see why. We talk about his dog Gus, the connection between our desire to tame both poetry and animals, Keats, Herrick, Counting Crows, and Flannery O'Connor's peacocks.

Hold on to your hats!

First, a little about J.P.: he attended Sewanee: The University of the South and received his MFA in poetry from Johns Hopkins University. He is currently a doctoral student in Literature & Creative Writing at the University of Utah, where he teaches undergraduate writing, serves as managing editor of Quarterly West, and helps curate the Working Dog reading series. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in AGNI, Best New Poets 2015, Cincinnati Review, West Branch Wired, The Journal, and Ninth Letter Online, among others. He will begin a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University in Fall 2017. Find more at www.jpgrasser.com.

Tell us a little about your dog Gus. Maybe a story that exemplifies his role in your life?

Gus: (named after Gustav Klimt, the Art Nouveau painter, and/or Gus-Gus, the rotund & ruddy rodent from Disney’s Cinderella).

Gus: sweet & caring, regal & dainty, wild & vicious.

To elaborate: one afternoon last March, while teaching, I received a flurry of phone calls from my partner. When I managed to get in touch, she was beside herself, nearly inconsolable. She & Gus had been hiking on the Bonneville Shoreline Trail—a tract along Salt Lake City’s east side, which had once been the shore of the Bonneville inland ocean, a tract which is now mostly domesticated. Mostly.

As she tells the story, Gus had been trotting at her heels with all of his characteristic amiability—just enjoying the early spring weather, taking in the new smells, soaking up the good light. In a flash, he dove into the scrub brush. Just as quick, he re-emerged with a Magpie firmly in his maw. She got to him just in time to see an iridescent, blue-tipped wing disappear down his throat (whole).

When the scene wrapped up, he returned to Maggie’s side, calm & sweet as ever.

Getting to know Gus, watching our lives interweave & imbricate, has been much like this. He possesses a ferocity of spirit, an untamable instinct, which I admire. Which I’d like to emulate. And yet, there’s a grace in him too. Which I’d also like to emulate.

"No good poem can be written in this way—we must, I think, have one foot in this world & one in that other, indescribable realm."

Where does Gus fit into your writing rituals?

At first, he didn’t. Gus is nothing if not a fetch-fiend, and I usually like to write outside. Which meant, of course, I couldn’t get a thing done. Outside time, for Gus, means playtime. He never gets tired of it.

So, like him, I’ve learned to adapt. I write at the kitchen table most days now and, at times, forget he’s here. That is, until he decides to curl up at my feet.

This has struck me, of late, as a metaphor for the process of composition in general. For us, as writers, when all cylinders are firing in tandem, there’s a breed (pun intended) of absolute absorption that occurs. We forget the world; our psyches recede from it. But no good poem can be written in this way—we must, I think, have one foot in this world & one in that other, indescribable realm.

When I’ve lost myself to the pure pleasure of writing, Gus happily reminds me of all the multitudinous joy & pain & love & suffering going on, at that very minute, in the space outside the margins.

In our pre-interview banter, you noted you saw some connection between how we engage with poems and how we engage with domesticated animals. In essence – please forgive the rough paraphrase here – our aim seems to be to contain both a poem’s and an animal’s wildness. But as you said, “Wildness can exist in even the well-mannered poem.” Can you elaborate on this connection?

Yes! Advance apologies for the grad-school density to follow:

In The Well Wrought Urn, Cleanth Brooks gives one definition for poetry as “the language of paradox.” Or, to go the Keats ‘Negative Capability’ route, one might say good poetry is (un)simply uncertainty unbridled. But isn’t that also the definition of all creatures? Of Gus? Of (your pup) Bowie? Of us?

I often find myself gravitating toward received form as a way to mete & measure this uncertainty—one can’t stare into the void too long without a tether (or leash!). But Gus has made me truly realize that even the most domesticated of forms—the perfectly constructed Elizabethan sonnet, say—must likewise incorporate surprise, variation, spontaneity. It’s not so much duality as multiplicity. (I’m thinking here of Herrick’s line from “Delight in Disorder”: “I see a wild civility.”)

When Gus first came home with us from the humane society (his third home in six months), I was hell-bent on training him. He was going to be the best-behaved dog in the Mountain West. But he isn’t, not even close—he is a dogged dog, to be sure. And now, I love him for his wild, independent spirit, not in spite of it. I love him for his multiplicity.

"We’re animals too, just as subject to the whims of the world as a puffin, a tulip, a dung beetle."

In your poem “Fetch” that appeared in Birmingham Poetry Review, you write: “Stay, I say, and Sit – / exhibits of my neuroses…”

Does this hint at what you think drives our fear of what’s wild? Or, more specific to this conversation, what drives our need to control both wildness on the page and in our animals?

Many of our neuroses & anxieties, I think, stem directly from this fundamental dissonance. We like to think of ourselves as higher order beings—fully rational, fully civilized, fully in control. But, we’re not. We’re animals too, just as subject to the whims of the world as a puffin, a tulip, a dung beetle.

We’re happy to acknowledge this in abstract discourse, but we’ve done everything possible to hide this fact from ourselves. We use forks & knives & spoons (god forbid we eat a salad with our hands). We’ve invented commodes & bidets (for sanitary and sanity reasons, I’d argue).

For the past year or so, I’ve started to work toward a regular practice of Mindfulness. Which is, of course, exactly what our dogs practice every day. They live in the present. They control what they can. They don’t worry about the rest. What great teachers they could be, if only we were more willing pupils.

Your poems are so drenched in rhyme, slant rhyme, assonance, and consonance. I could pick a number of examples, but let’s go with “Surrender the Animal” because those last few lines won’t come down from my mind:

Me: too rational,

too busy thinking what these people thought

of me, wearing a suit to a funeral

in Nebraska. Maybe regret’s futile.

Still though, I wish I’d screamed my animal

grief like the animal I think I am.

What is the ideal role for sound to play in a poem?

The role sound must play in a poem is exactly that: serious play, playful sincerity. (If you see Gus with his tennis ball, you’ll see—he gets it.)

"We must grieve the living if we’re to appreciate them, if we’re to accept their eventual going."

A follow-up about that poem: you draw on how animals grieve to illuminate human grief. How else have animals informed the way you explore human complexities on the page? Has Gus helped in this regard?

I’m not sure this answers the question, but, being a poet, how could I pass up the opportunity to share some thoughts on mortality.

By comparison, death makes the previously mentioned problems-of-being-human quite minor. (To quote Larkin: “The mind blanks at the glare.”) Think of the pomp & circumstance we ascribe to death—the ornamentation of funeral rites, 21-gun salutes, the Minwax-sheen of the casket itself. We ritualize & aestheticize death out of terror and uncertainty. We make sure the urn is well-wrought.

But this only takes us farther from the grief-work we must do, the excavation. On a farm, death is flat, plain, and part of life. You don’t get used to it, but you accept it. (This time, Harold Bloom, on Keats: the poet’s “gift is one of tragic acceptance.”)

Since Gus has joined our pack, we’ve already begun the process of grieving for him. He’s only two. He’s healthy. He’s impossibly energetic. But we must grieve the living if we’re to appreciate them, if we’re to accept their eventual going.

There’s that age-old adage, perhaps best summarized (for my generation, at least) by Counting Crows: “Don't it always seem to go / That you don't know what you've got ‘til its gone.”

Only in accepting the impending gone can we know what we’ve got.

Your poem “Dog,” which appeared in diode, opens with the epigraph “Let them have dominion” from Genesis 1:26 and uses an uncle’s treatment of a dog as a microcosm of that dominion. Can you talk more about the premise of this poem and what you hope readers take away from it?

The passage from Genesis reads, in full, “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

But why shouldn’t dogs have dominion too? Or any other animal, for that matter? If you ask me, there’s something creepy about this transitive god-complex.

But, again, we’re back to the idea of control and domestication. To me, the poem is about averting my own glance, about taking pleasure in suffering, when I was a child. My uncle, who was once a professor of biology (and who, therefore, unequivocally knew the scientifically-verifiable ‘interrelatedness of all things’), kept dogs chained down by the ponds on my grandparents’ farm. Why he did this, I don’t know.

But this is a phenomenon almost entirely distinct to humans (if we disregard, for the time being, cats and orcas)—the malevolent thrill we find in exerting power over other creatures.

We all know the one about the ants and the boy and the magnifying glass.

Or, to take the Aristotelian route, it’s a poem about the competing desires of egoism and the supererogatory, avarice vs. charity. Or, simply put, self-importance winning out over fundamental goodness. We must care for the world & all its beautiful, beautiful things.

"...there’s something creepy about this transitive god-complex."

A metaphor or simile for Gus?

Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks.

Daniel M. Shapiro: Rules You Never Considered Breaking

Poet Daniel M. Shapiro on his pupper Pepper, how a poem has changed his mind before, how he makes editorial decisions, and why he avoids writing about certain topics.

I'm still grieving the election results hard, and I don't know what to say other than I don't want to think about silver linings or "bridging the divide." (You don't get to threaten the majority of Americans and advocate for our oppression and demand that we respect "different opinions." Nah. You get to have an opinion about a favorite ice cream flavor, not the persecution of entire communities.)

But I am grateful for people like Daniel M. Shapiro who remind me that the world isn't a complete garbage can. Thanks, Dan.

Daniel and I spoke before the election, so we don't get into that here. But I know my dogs have been a reliable source of comfort since Tuesday, so I'm glad we get the chance to honor our small companions and talk about poetry because, dammit, something has to get us through.

A little about Daniel M. Shapiro: he is the author of Heavy Metal Fairy Tales (Throwback Books, 2016), How the Potato Chip Was Invented (sunnyoutside, 2013), and The 44th-Worst Album Ever (NAP Books, 2012). Some of his recent work has appeared in Ink in Thirds, Bitterzoet, Uppagus, and Forklift, Ohio. He is a senior poetry editor and reviews editor for Pittsburgh Poetry Review, and he interviews poets at Little Myths.

Tell us a little about how your pupper Pepper came into your life.

Our 13-year-old golden retriever, Heidi, had died more than five years ago, and I was distraught to the point of telling my wife, Kris, that I didn’t think I would want a dog again. Previously, we had discussed getting a cairn terrier, but I had wanted a rescue dog and thought it would be unlikely to find a cairn that way. A couple of weeks after Heidi died, Kris sent me a link to a cairn rescue home page with a picture of an absurdly cute dog, and she wrote, “Maybe we could get one like this sometime.” Even though I had sworn off dogs, I wrote back: “I don’t want a dog LIKE that one. I want THAT one.” So we drove a couple of hours to Ohio and picked her up. She was wormy and weighed 2 pounds. She looked like a Beanie Baby.

What’s the biggest perk of having a dog? The biggest drawback?

The biggest perk is that you get to have a family member that provides unconditional love. She’s perceptive and knows when people need to be left alone or want cuddles or kisses. I don’t think there are any major drawbacks. I don’t like having to board her when we go out of town, but that’s probably it.

Has Pepper had any influence on your writing? If so, how?

I think she has influenced me by helping to provide a comfortable setting. I always write in the same chair, I always put my feet up on an ottoman, and she almost always lies there on top of my legs. She contributes to the right mindset to write.

"I don't want my poems to suggest I have lived or felt things that belong to other people."

If you had to describe your poetry wheelhouse – topics you’re most likely to write about – what would it be? Anything you try not to write about?

My wheelhouse is typically rock or pop music, but it has included other elements of pop culture. I have some new poems based on board games, for example. I try not to write about topics or themes I’ve seen repeatedly, such as nature. I feel like I would be competing against everyone else who has done that, and I wouldn’t have anything to add. I also avoid topics I’m interested in but don’t believe I’m the appropriate speaker for; I don’t want my poems to suggest I have lived or felt things that belong to other people.

True or false: a poem has changed your mind before.

Probably 10 years ago or more, I started to read books by Russell Edson, James Tate, and others who blurred the boundaries between poetry and prose. They broke what I had considered to be rules I never would’ve considered breaking, and their poems encouraged me to be more open to whatever structure or odd subject matter suited my needs as a writer. Now I write more prose poems than anything else.

As an editor for Pittsburgh Poetry Review, you’re no stranger to slush. What are the hallmarks of a poem you’d want to publish?

I am drawn to poems that express the individuality and/or specific obsessions of a poet but that covertly reveal an element of universality. I find that a lot of writing uses the opposite approach; it’s more dedicated to universality, and the unique ideas or experiences of the poet are secondary. The latter scenario can create a sameness in the submissions we see.

One of the best poems we’ve published in PPR was about baseball, but of course it wasn’t about that only, and you could argue it wasn’t about it at all. The poet blended her love of baseball with the culture of where she grew up, her adolescence, her relationship with her father, etc. So I got a sense of why only that poet could write that poem, but the drive of the language, combined with “America’s pastime,” provided a broader appeal, as well.

"The best poets can rearrange topics I tend to avoid—e.g., religion, which usually inspires a kind of emotional shorthand—and find something in the topics I never would’ve seen without their help."

And a follow up: any pro tips on checking an aesthetic bias while reading submissions?

If a poem covers a topic I think has been done to death, I focus on the poet’s approach. Are the trees really trees? Maybe a poem starts as a conventional tree poem, but the trees become vengeful and start to kill people who are ruining the environment. Turn the tree poem upside down, and I’m there. If it’s a dead cat poem, will it become a zombie cat poem (please?)? The best poets can rearrange topics I tend to avoid—e.g., religion, which usually inspires a kind of emotional shorthand—and find something in the topics I never would’ve seen without their help.

What do you think is the best poem you’ve ever written and why?

I don’t know if it’s my best poem, but my favorite poem I’ve written is called “Don Knotts Returns to His Hometown of Morgantown, W.Va., 1982.” I like it because people always laugh when they hear the title, but eventually they realize the poem is quiet and sad. I like how the poem can be many things: silly, poignant, surreal, journalistic, etc.

A metaphor or simile for Pepper?

Pepper is like a neighborhood bar: occasionally deafening, filled with love, on the verge of a pratfall, and all-out fun until she winds up in a deep sleep.

Megan Peak: Something Other than Myself

Poet Megan Peak on self care, bridging the gap between thesis and manuscript, and poetry's role in effecting social change.

I don't know about you, but I've been keeping my eye on Megan Peak, a hella smart writer who is already penning some of the most memorable poems I've had the good fortune to read. She's bound to do amazing things over her career.

And so as a Halloween treat (no tricks), you get to spend some time with Megan and her dog Radish. We chat about how Rad helps her put self care first (and how writing is part of that process). We also discuss bridging the gap from poetry thesis to book manuscript and poetry's role in effecting social change, including dismantling rape culture.

I told you – all treats.

A little about Megan: she received her MFA in poetry from The Ohio State University, where she was former poetry editor at The Journal. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming from Blackbird, DIAGRAM, Four Way Review, Indiana Review, Muzzle, Ninth Letter, North American Review, PANK, The Pinch, Ploughshares, Sou'wester, Tupelo Quarterly, and Valparaiso Poetry Review, among others. She lives in Fort Worth, TX with her partner and her dog Radish. You can find her at www.meganpeak.com.

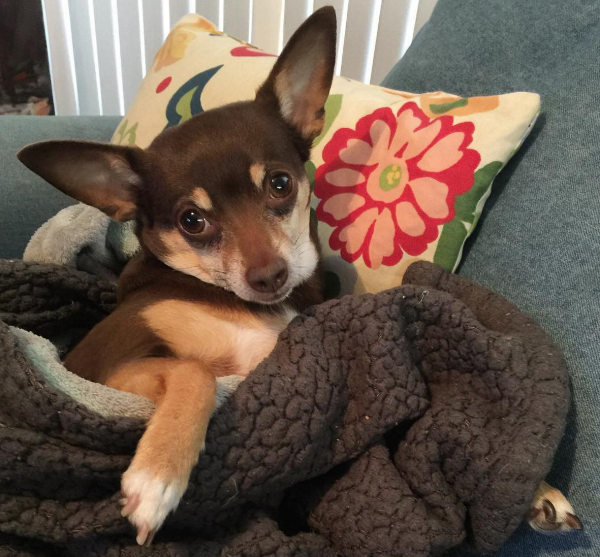

Tell us a little about Radish and how she came into your life.

My family has always had pets. There hasn’t been a time in my life when I didn’t have an animal of some kind as a part of my daily experiences. So, when I moved to Ohio from Texas for my MFA, I felt that void intensely. And, if I remember correctly, the five of us poets in the incoming MFA program were some of the most heartsick people—all coming from some personal grief: break-ups, homesickness, sheer loneliness. But, as the year went on, I was comforted and enlivened by my cohort, my professors, the act of coming to the page day after day, the poems. So, when I rescued Radish in my second year at OSU and she was the one mistreated, malnourished, fearful, I was ready to tend to something other than myself. She taught me a great deal about relearning how to trust and practicing patience.

From what I can tell, Rad is part Chihuahua, part Miniature Pinscher. The people at the shelter named her Radish, and I couldn’t agree more with the name. She has a little kick to her—bold but sweet. She’s fiercely loyal, smart, and resilient. I think she misses the snow and the longevity of the Ohio winter, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter because she is such a mama’s girl. She is happy wherever I am. She is sitting on my lap right now, belly thick and rhythmic with whatever little dream she is having.

"I was ready to tend to something other than myself."

Throughout these interviews, I’ve talked on and off about my experiences with Dog Magic. It’s difficult for me to picture how much different a person I would be now if it weren’t for my dogs. (For example, my dog Pete is the reason I became a vegan. She’s also the reason I’m a very reluctant traveler. She hates traveling.) Have you noticed any significant way your life has changed because of Radish’s companionship? Has she impacted your writing?

I think, with Rad’s help and the outright passage of time, I have become more aware of my need to balance self-care with that of comforting others. What I love about Radish is that if she doesn’t want to be crammed on the couch with my partner and me while we watch a movie, she will jump down and curl up in her bed. I love that independent impulse in her, knowing when she needs us and when she would like to have some space. There have been times in my life when that boundary has been slippery at best, and when I notice these small moments with Radish, I find some affirmation in my impulses to be alone, to reach out, and/or to serve others.

Going off of that, one of my needs is to write. So, Radish does influence my writing, I suppose, indirectly. Writing exists, for me, as a form of self-care because without it I become anxious, overwhelmed, unable to process my surroundings and the events in my life. She aids in that ritual of returning to the page each day.

What’s one poem you couldn’t have written without a spark of inspiration from the animal world? What unexpected place did it take the poem?

Actually, my whole second manuscript that I am currently working on draws directly from the animal world. Egrets, horses, does—the project emerges from the strange connection between sisters and place and what drives one away from and back toward family. The manuscript explores the wild and the domestic, the exterior worlds of New Orleans, of swamps, of the Texas plains and the interior spaces of the home. It focuses on the female experience of marriage, of sacrifice, of daughterhood and sisterhood. The project attempts to examine that very tender, wild thread that links sisters as they bear witness to each other's trajectories. Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual.

One poem, “The Egret Bride,” which was recently published in Iron Horse Literary Review, is one such piece. It was one of those pieces that had no title, that began after reading someone else’s work (Kiki Petrosino, I think!). Ultimately, I found a way to speak about marriage, what one might lose in that union, and the ways in which family influences our choices. The poem documents the speaker watching as the sister transforms from girl to egret, from daughter to wife, from connected to estranged.

"Animals emerge as a way to understand not just place but also the speaker’s relationship to and with her sister—one that is animalistic, violent, protective, and spiritual."

You graduated from OSU with an MFA in poetry last year (belated congratulations!). I don’t know if this is true for you, but I graduated expecting to just shop around my thesis as my book and that would be it. But after sitting with it for a couple months and even after getting a few finalist bites, I realized I still had more work to do before the thing was a legit manuscript for me. What has your experience been like? How much distance is there between your thesis and your current manuscript?

Oh, I definitely feel that. I knew the thesis wasn’t where I truly wanted it to be after my defense. My professor and mentor even said, “You have a thesis, but now we need it to be a manuscript.” I’m a perfectionist, so I don’t know if it will ever really be “done,” in my opinion, but the fact that I am comfortable moving on to this second project is a good sign that the manuscript is in the right place. And yes, the manuscript is pretty different than the original thesis—different title, different order, new poems, all of which has created a more compelling arc than what I originally had. Here’s to hoping that it won’t be a bridesmaid for much longer!

Your biggest, most ostentatious poetry goal that you may not even want to publicly admit? Here, I’ll share mine: I want to win a freaking Pulitzer one day.

Oh, goodness. I suppose I would love to be financially stable from my poems and books one day, to be able to rely solely on my writing as a source of income. I don’t know if that will ever happen with poetry, but one can dream. On a broader note, my partner and I are working on a graphic novel together, and I would absolutely LOVE 1) to finish it and 2) to have some network like HBO pick it up. That would be the life.

Several of your poems are about sexual assault: “Elegy with a River Inside It,” “What I Don’t Tell My Mother About Ohio,” and “When Asked If I Said ‘No’.” How do you balance the beauty of language when writing about something so violent and traumatic?

I’ve always remembered this quote by Plath from her journals:

“Some things are hard to write about. After something happens to you, you go to write it down, and either you over dramatize it, or underplay it, exaggerate the wrong parts or ignore the important ones. At any rate, you never write it quite the way you want to.”

The poems that you mention and others that address assault and sexual violence came from this very raw and unhinged place at first. Just me trying to get it down on paper. And yet, they never felt “right” or “done” or whatever you say in terms of finishing a poem. People in my workshop never really knew what to say about them, except that it was brave or important or necessary work. While it was nice to hear, it wasn’t helpful. So, I had to find my own way to frame these poems, and that usually emerged by juxtaposing the “drama” or trauma of the event with the violent beauty of place, environment, weather. I think it helped me, and I suppose the speaker of the poem, to fluctuate the lenses on these traumatic moments, which felt truthful to the experience and gave the poem / reader perspective.

"Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict."

And a headier follow-up: what role do you think poetry has in changing rape culture?

Historically, I think we’ve always looked to writers, poets especially, in times of chaos, suffering, conflict. Even now, we have poets writing necessary pieces ranging from race and gun violence to the injustices of the current academic job market in regards to contingent faculty. So, I think poetry has and always will have a vital role in bringing awareness to cultural and social trends and issues.

Will my poems change rape culture? I don’t know. But magazines publishing these pieces like Vinyl, Winter Tangerine Review, Tinderbox Poetry, The Adroit Journal, etc. are dismantling that taboo cloud that hangs over the subject of sexual assault and rape—something that happens to too many women, girls, and members of the LGBTQ community. I don’t know what my poems will do in regards to changing rape culture, but I know that writing / talking about it is the only way to show the world that it is an unacceptable violence that occurs all too often in our society.

A metaphor or simile for Rad?

An America’s Next Top Model contestant. She can smile with her eyes, and she’s got a snout for days. She’s got a sturdy following on Instagram of 2,200 admirers and counting. You can follow her at @radthedog to see all of her shenanigans and beauty shots.

Fox Frazier-Foley: What You're Given, What You Use

Fox Frazier-Foley on rescuing her dogs, building a community as a writer, what a successful political poem doesn't do, and how editors can be more inclusive.

I was mindlessly scrolling Facebook the other day when I came across a video my friend posted about a man in Aleppo, Syria, who takes care of abandoned cats. Destruction and loss all around him, and here's this man, doing what he can to make the world a little kinder.

And that's one of the things Fox Frazier-Foley and I talk about today: the concrete ways she works to "make a dent in the terrible terrible awful," whether that's by rescuing her dogs or carving out space for writers to share their work. Bonus: she has some really good pointers for writers who are shopping manuscripts and for editors on inclusive publishing.

Before we get going, meet Fox: she's author of two prize-winning poetry collections, Exodus in X Minor (Sundress Publications, 2014) and The Hydromantic Histories (Bright Hill Press, 2015), and editor of anthologies Political Punch (Sundress Publications, 2016) and Among Margins (Ricochet Editions, 2016). Fox created TheThe Poetry Blog’s Infoxicated Corner, which she edits and curates. She is founding EIC of the small literary press Agape Editions.

Tell me a little about your dogs Dalí Nimbus and Oskar Wild.

Dalí was the first of the two to join our family; she's a Maltese & West Highland Terrier mix. It was love at first sight when I went to meet her. A larger, male dog came up and tried to menace her and assert his dominance over her, and she threw him on his back, then stood over him barking into his face. I thought it was so funny that she had such a tough-as-nails attitude (which would come to be less entertaining later—when she attempts to shout down the sky during midnight thunderstorms, for example, which is a self-assigned responsibility that she takes very seriously). Anyway, she literally jumped into my arms when I met her, and I knew that she was meant to be with me.

Oskar Wild is also a rescue dog—a Chihuahua mix, we think maybe a little corgi because he really likes to herd people. He'll nip at our ankles if one of us leaves the room when the family is chilling together at home to try to herd us back to the “pack.” We went through so much to get him! It actually took the help of several people, partly because he was bounced around a little bit before he made it to the shelter, and partly because the shelter lost him for a couple days after we had paid all the fees and finished all the paperwork! Their computer records showed that he had been taken to the vet, and the vet kept insisting that Oskar had never been brought to him.

So when we came to the shelter to find him, the staff told us we should just take another dog instead. I had spent several days bonding with him, and so I told them pretty emphatically that I didn’t think that that was a very good idea. We ended up searching the shelter, even though they were closed that day, and finally found him locked away in an empty part of the shelter that is only used for quarantine. No one could explain who locked him away or why. He had never even been taken to the shelter vet at all—which is something they won’t budge on: every dog has to be neutered or spayed by their vet specifically, so we had to wait a couple extra days, during which time I was a complete basket case and probably not the most pleasant person to be around. But at least the story has a happy ending! He’s curled up on my hip right now, making a complete baby face at me so I’ll stroke his (comically enormous and absolutely adorable) ears.

"It’s kind of like the Red Queen model of evolution..."

You know, I understand why shelters make folks jump through hoops to adopt animals—obviously, no one wants the animals to end up somewhere that’s not a good fit, but sometimes those hoops seem to box out really worthy owners. I’m glad that didn’t end up being the case with you and Oskar Wild!

So let’s segue to this question: why is it important to you to rescue dogs?

I know this is going to sound pretty dark, but I’m constantly aware, or almost constantly aware, of the fact that this world is a pretty terrible place. We talk about “progress,” and I guess that’s true—progress does happen—but in my mind, it’s kind of like the Red Queen model of evolution—many humans work so hard to be better and do better and make things better for as many people as they can—but the end result is that the human race is (at best) just barely able to keep some semblance of balance between what we might simplistically refer to as forces of good and evil. I suspect that the world has always been this way, and it will probably always be this way, until it ceases to exist.

And so, given that that is my worldview, I have a tendency to concentrate my efforts and energies in tangible or concrete ways that seem like they actually make a dent in the terrible terrible awful. So, obviously, rescue animals have usually had it pretty bad. I love animals and want to have them in my family, so to me, it makes sense to try to have that happen in a way that also helps reduce suffering. I know it’s a drop in the bucket, really, but that’s my general motivation.

Do your dogs affect how you think about or write about animals in your poetry?

They probably do, but probably not in a very overt way. I do think my dogs keep me very aware of the fact that we are all animals. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, either—I know we usually use it in a pejorative way, right, like a really heinous crime happens and we’ll say, “Only an animal could do that,” or “Even animals don’t do things like that,” but I think neither of those statements are really true. Again, I know this will probably sound dark, but from a practical standpoint that history has borne out pretty convincingly that humans do way worse things than animals—and that’s really saying something, because nature is pretty brutal.

But, overall, my dogs remind me that some animals—and this includes human animals—are extremely kind and gentle and wise, and some are very aggressive and predatory and cruel, and most are probably some combination of those two extremes. I know that we like to think we are not really animals, but we are. We are. And those ideas influence pretty much everything I write.

"I know that we like to think we are not really animals, but we are. We are. And those ideas influence pretty much everything I write."

I’d love to talk a little about your poem “St. Gemini Collages Photographs of Distorted Dolls in Vulnerable Poses Together With an Ancient List of Indigo-Colored Objects, and Glues Her Revelations Inside the Book of Truth and Water,” a poem you said “not only expresses how animals function in my work, but I think the poem itself is kind of animalistic.”

A lot of what it was trying to interrogate was the relationship within one human (animal) of predatory tendencies and fear or vulnerability (I guess qualities I would associate with feeling like “prey”). The reference to sirens / mermaids was intended to capture that as well. It's funny, because—this kind of goes along with what I was just saying about how I think people are animals—I also think that my dogs are very much like people. They have personalities. They can’t tell us everything that they understand, but they understand so much. (Look! Science agrees with me! Good job, science.)

To elaborate a little on one of my earlier answers, this poem is animalistic (and references those predator / prey qualities that I consider animalistic) because it reflects what I was saying about how my dogs can be wonderfully kind and sweet and loving, and yet they can also be terribly aggressive—sometimes in funny ways, like toward stuffed animals or Cheez-It crackers, and sometimes in less-funny ways, like toward each other (they’ve gotten into a couple knock-down, drag-out brawls over stuffed-animal toys, which I guess sounds a little funny after the fact, but when it’s happening it’s definitely NOT funny)! And so this poem was kind of a nexus for my considerations about ways in which we humans can love deeply and be enlightened and wonderfully kind, but at the end of the day, we also have incredibly violent tendencies coded into our DNA. (I don’t mean to say that I think everyone is physically violent, but I think we’ve all fallen into the trap of saying, “Oh, so-and-so couldn’t have done that awful thing—he’s such a nice guy!” But the truth, of course, is that sometimes even nice people do things that are aggressive or hurtful, things that they shouldn’t do.)

Maybe this stuff explains why my deep love for my dogs is often characterized by extreme silliness—because everything, all those really deep and terrible, visceral truths are always right there at the surface when I see them. It's a weird, refreshing kind of honesty—and the expressions of joy and tenderness they offer are really honest, too. You know, they literally celebrate when they wake up in the morning. They realize they're awake, and look at me and the tail waggles start, and then they start sneezing uncontrollably (this is how they express serious excitement—they sneeze uncontrollably, and it's the funniest thing ever), and then Dalí prances around digging excitedly on the bed and Oskar chases his tail in circles (he does this when I'm sad, too, because it cracks me up—I find it so endearing that he literally tries to make me laugh when I'm crying or sad). And then, like, they see a housefly moving through the air and their predator faces come out. Their lizard brains take over and they don’t want anything other than to catch and kill and eat that fly. I guess I’m glad I’m the mama and not the fly!