Rachel Mennies: Interrogating Our Animalness

Rachel Mennies talks about the subtle and dynamic ways her dog Otto has shifted her worldview, his wagging presence in and around her poems, and how animals help us understand ourselves.

If you know Rachel Mennies, you don't need me to tell you she's a triple threat of smarts, talent, and generosity. If you don't know her, have a seat, dear reader, and prepare to hand over your heart, silver platter and all. There's perhaps nothing more rewarding than listening to a poet discuss something they deeply love, and for Rachel, that's her dog Otto. She talks about how he came into her life, both the subtle and dynamic ways he's shifted her worldview, his steady presence in and around her poems, and how animals help us understand ourselves.

Before we get to it, a little about Rachel: She's the author of The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards (Texas Tech University Press, 2014), winner of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry, and the chapbook No Silence in the Fields (Blue Hour Press, 2012). Her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Poet Lore, Indiana Review, Black Warrior Review, and other literary journals. She is the series editor (2015-) for the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize at Texas Tech University Press, she teaches in the First-Year Writing Program at Carnegie Mellon University, and she is a member of the editorial staff at AGNI. She lives in Pittsburgh with her dear pup Otto.

How did Otto come into your life?

About three years ago, my husband and I decided to tackle the responsibility of dog ownership, after wanting a dog for many years prior. Moving from that general decision to the specific decision of which dog to adopt—we went the rescue route—was the hardest part of the process. The days spent on Petfinder meant reading one heart-tugging story after another, especially knowing we could only take on one dog and, since we have an apartment with no yard, had to choose a dog carefully that could handle our city-living situation. After all the reading, we went to exactly one shelter and Otto, an Italian greyhound-beagle-other mix who was about four months old at the time, was the second dog we walked. We brought him home the next day.

Did you grow up with pets or was getting a dog a brave new world for you?

My parents got our first dachshund, Maddie, when I was a senior in high school, so I spent most of my time at home without a dog in the house. They now have two sibling dachshunds—Sammie is from the same parents, but a different litter than Maddie—and Otto plays with them as much as Maddie and Sam will allow it when I come home to visit. Because Maddie arrived right as I was preparing to leave home, I participated very little in her dog-care routine—Otto’s mostly “brave new world” territory for me.

“We’re both habit-seekers, and we’ve learned each other’s routines quite well at this point.”

Tell me a story that gives a good snapshot of your relationship with Otto.

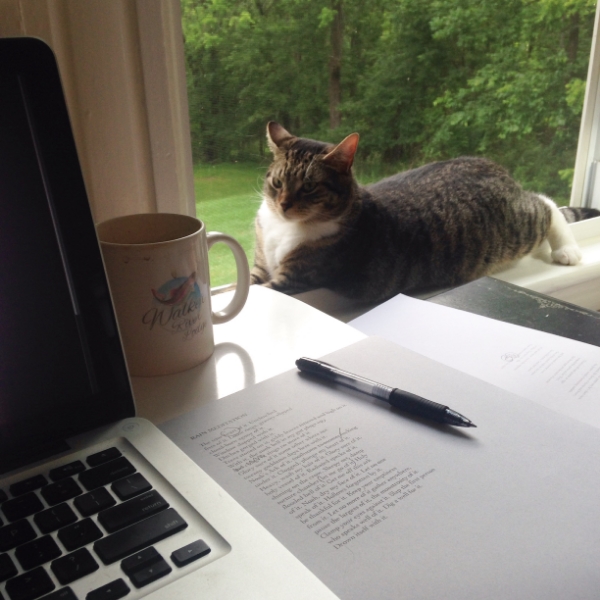

As Otto’s gotten older—he’s three now, so no longer a puppy—he sleeps for longer and longer into the day, while I’m a true morning person. He usually pads into my “office,” the room in our apartment that holds my desk and yoga mat and the best natural light (and a plant, if I’ve managed not to kill it), an hour or so past once I’ve made coffee and begun to work, and he sets his head on my knee to let me know he’d like to go outside. We’re both habit-seekers, and we’ve learned each other’s routines quite well at this point.

You mention how Otto's schedule helps keep your writing life structured in your blog post "Poetry on The Animal Calendar" for the Tahoma Literary Review. (Oh, how we live and die by the dog schedule in my house.) I'm fascinated by this very practical and direct way he's influenced your writing process. Other than the built-in time blocking (bonafide productivity hack: get a dog!), are there other ways Otto's presence has helped you write poems?

I think often about the depth of affection a human earns from a dog once the relationship’s had some time to grow: Otto seeks my presence and time and touch so much in exchange for what to me seems like very little (food, water, shelter, predictable and consistent kindness). The bond helps me write because it exists dependably and without question—often the opposite of how I feel in terms of the writing process.

Otto and I had to earn this slowly in each other, which may also be familiar to other rescue-dog owners. The first month we adopted Otto, which also happened to be the first month of my fall semester, he growled at us from under our couch (thankfully, he’s outgrown being able to fit under there…), destroyed a few of our belongings, pulled hard away from me on his leash, and fought to get out of his crate daily. He almost escaped from our car at the animal shelter. He had no idea who we were, where he’d gone, or why we’d brought him to us. I thought for the first month that I couldn’t handle dog ownership.

But the semester continued, and he calmed down, and I found that he became the calmest when I sat beside him on the couch, each of us on a separate cushion, and I took out my computer and wrote (or graded papers). With time, he eased closer; now, if I write on the couch, he stretches out long between my legs and the couch’s back, burrowed in as close as possible. If I snap the laptop closed, he thinks it’s time for a walk. His calmness and affection feel sanctioning, especially in the many moments that I find the writing process difficult or anxiety producing. Sometimes I read drafts aloud to him, which is a comfort, too.

“The bond helps me write because it exists dependably and without question—often the opposite of how I feel in terms of the writing process.”

We've got to talk about "Elegy with Attack Dog," a poem I will remember as long as I'm on this green earth, especially the closing lines: "And you lie awake / and stare at the loss, rubbing / the soft spot at your throat / that misses the shape / of its mouth." I love the metaphor of the dog to illustrate the mechanics of grief. Can you talk a little about the inspiration behind that?

A couple of summers ago, two friends of ours had taken their own two dogs out for a run when a neighborhood dog broke from his yard and attacked all four of them. It’s a long and sad story, but at the end of it, only one of their dogs survived, and Animal Control eventually euthanized the “attack dog.”

As a dog lover, stories like these—in which the creature we love, that we let sleep in our beds and eat from our tables, bares its teeth and reminds us of its power to destroy—are especially difficult to process. In the specific grief I felt for my friends, I began thinking about the fear the incident left behind in me (that whole summer, each dog that ran up to Otto at the park or on the street made my pulse elevate) as a metaphor for a broader sense of loss—how long it takes, if ever, to pass through the process of grief into permanent safety or calm.

I moved practically from these thoughts into a draft of “Elegy…” in a writing workshop I was spying on that was led by the poet Jill Khoury—we were teaching in a Young Writers program together at the time—who had tasked the high-schoolers with writing a poem that utilized anaphora. I started with the specifics I remembered of my friends’ attack—the dog going for their dog’s neck, and holding on—and the poem unfolded slowly from there.

Let's talk about the non-metaphorical dogs and animals that show up in your poems. Why do you think animals have such a prominent place in poetry at large and in yours in particular?

I write often about the human body and its animal-feeling; I wonder if some of our writing about animals comes partially from our desire to interrogate our own animal-ness. To that end, I’m often struck by the strangeness of living with a domesticated animal, but an animal nonetheless—how at times I can see Otto give into what we might call his “animal nature,” despite his training and domestication. A couple of months ago, Otto (somehow) grabbed a live bird out of the air in his teeth and only let go once I pried open his jaw. He’d just spent the morning sleeping beside my desk, docile, but right in front of me—and in a split second—he’d killed a bird. In moments like this one I’m reminded of my own human-animal modulations between desire, restraint, action.

Otto also makes his way into my poems because of our proximity—I see his face and body in each of the rooms of our apartment, in the park across the street, in the backseat of my car. I probably spend more time with him than any other living creature, so it makes sense that he appears in my poems, too.

“I wonder if some of our writing about animals comes partially from our desire to interrogate our own animal-ness.”

Your favorite poem about an animal or with an animal in it?

Paisley Rekdal’s “Why Some Girls Love Horses” and much of Robin Becker’s poetry, as animals (especially dogs) figure prominently throughout her work. She’s written two of my all-time favorite poems specifically about rescue dogs: “Rescue Parable” and “Rescue Riddle.” The lines “When she takes her morning tea, he settles / beside her – body of law and praise, / procuress, his winter and summer hearth” make me think of the routine I have earned with Otto.

Has caring for an animal helped shape how you see the world around you? If so, how?

Entirely, and that surprised me. My husband and I don’t have children, so we often hear from others that Otto is our child—a joke I’ve made a few times myself, too. Before we adopted Otto, I always rolled my eyes at people who referred to their dogs as their children, and I still find the comparison tenuous as I watch some of my friends become parents, but where I do see similarity (I imagine) is the way that keeping any sort of creature alive puts you on a spectrum of tested patience and earned love. I have agreed to care for Otto as long as he is mine; there is no opting-out or break-taking, because forgetting him would harm him. Even if he destroys something (his most recent chew-obsession, horribly, has been books!) or disobeys me, there is still no opting-out. There is more work to do to keep him behaved, perhaps, or longer walks that must be taken, but there is no backing away from the caretaking altogether.

I look at other dog owners in the park with an understanding that I didn’t possess before Otto’s adoption: what I’m understanding is what it feels like to have offered yourself up to an animal, knowing both the vastness of the work and the even more vastness of the reward, the love.

“What I’m understanding is what it feels like to have offered yourself up to an animal, knowing both the vastness of the work and the even more vastness of the reward, the love.”

Writing can put me in a weird headspace, but I've found that my dogs help pull me back to the surface afterward. Can you relate?

Absolutely, yes. Otto has become a reminder to me of how to access simple joys when my writing has cost me them, and a signal back to participation in the daily life I’ve “left” while writing—I have to walk the dog, have to feed the dog, have to hug the dog.

A simile for Otto?

Otto is like a tiny missile (but one that gives you kisses instead of blowing you up at the end?). He’s focused and incredibly fast and target-obsessed (very greyhound), and once he’s spent all his energy and reaches his destination, usually the couch, he’s warm and immediately inert.

Amie Whittemore: The End of an Era

Amie Whittemore talks about her cats, the specific way grief works when a pet dies, and her advice for writing about that loss in a meaningful way.

Lovers, I hope you're as excited about the first-ever interview in the Pet Poetics series as I am, and what a way to kick it off. I got the chance to chat with Amie Whittemore about her cats, the specific way grief works when a pet dies, and her advice for writing about that loss in a meaningful way.

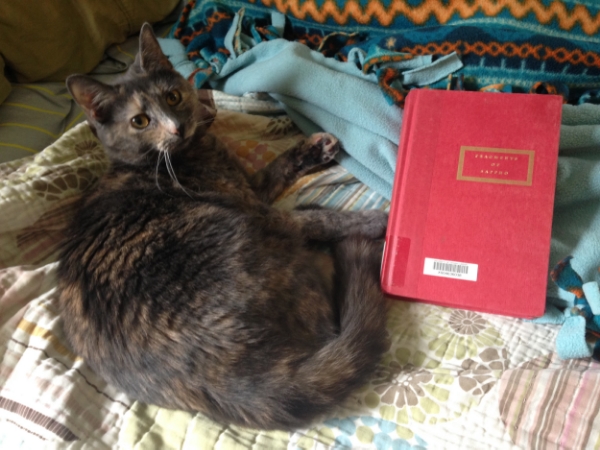

Before we dive in, a little about Amie: she is a poet, educator, and the author of Glass Harvest, forthcoming from Autumn House Press in July 2016. She is also co-founder of the Charlottesville Reading Series. She holds degrees from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (B.A.), Lewis and Clark College (M.A.T.), and Southern Illinois University Carbondale (M.F.A.). Her poems have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Sycamore Review, Rattle, Cimarron Review, and elsewhere. She spent a year photographing her former cat Stevens every day as an experiment in affection and Instagram filters. She lives in Charlottesville with her cats Chicory and Sage.

First of all, Amie, I'm happy to hear your cats Chicory and Sage are finally letting you get some sleep. Tell me about your decision to bring them into your life.

About a year ago, my beloved cat of ten years Stevens (yep, she was cat Stevens) died. As the first pet of my adulthood, adopted the year two grandparents died and lost the year after I divorced, her death marked not only a grievous loss, but also an end to an era of my life. She felt like the last anchor holding me steady; once she was gone, I felt entirely unmoored.

As anyone who has felt unmoored knows, it is largely impossible to imagine feeling moored again. Yet, with time, fantasies of kittens began to frolic in my mind. Having spent a decade fretting that Stevens was excruciatingly lonely as a single cat, I decided to adopt two kittens this time around. I began haunting the SPCA, waiting for love at first sight.

I met Chicory on one of these visits. She mewed at me as I passed her cage. I picked her up; she purred immediately, completely at ease curling up in my lap. A four-year-old boy sat on the floor next to me and informed me this kitten’s name was George and he was going to take her home when his dog died.

However, Chicory (whose middle name is George, in honor of her almost-owner) was there two days later when I decided I needed her in my life. That’s when I found a calico companion for her in Sage. Where Chicory is confident, charming, sociable, and playful, Sage is timid, frenetic, and (strangely enough) aggressively affectionate. They are loving and standoffish with each other in turns. I find their personalities, and their relationship, intensely interesting.

“As anyone who has felt unmoored knows, it is largely impossible to imagine feeling moored again.”

I know you lost your cat Stevens not long ago, and you reference her death in your poem “Year In Review." The line "Grew weepy in conversation about said dead cat / more often than is culturally appropriate" struck a chord with me. Did you feel pressure to meter how you wrote about her death because of the "culturally appropriate" expectation?

The poem picks up on the pressure I felt to withhold the intensity of my grief when friends politely shared their sympathies with me. Even recalling that grief brings tears to my eyes. There is not a day I do not miss Stevens.

I also think my poems about Stevens address a larger issue regarding grief in American society. I do not think we know how to honor it well in each other. We rely on tropes like “time heals” and “you’ll get over it,” though I think, in all our hearts, we know there is no “getting over.” And time may heal, but scars remain.

I think we could learn something from our pets about handling grief. They are such good caretakers of us in times of sorrow. They do not judge our weeping. They cuddle with us. They do not put time limits on feelings.

How did writing about Stevens help you process the loss? I'm thinking specifically about your poem “Song for Stevens” where there's heartbreak in every line. I can hardly read this without tearing up: “If given seven slides of calico hides, / I’d know which side was hers. If blindfolded / and handed seven cats, I’d know her by shape.”

I can’t read those lines without tearing up either. I wrote “Song for Stevens” while she was still alive. Writing that poem, and the poems that confront her death, helped me to honor the unique experience of adoring a pet. These poems give voice to the unbearable—and breathtaking—need to love something else unconditionally, passionately, and thoughtlessly. We have such a hard time doing this well with each other. With pets, we can learn to do this better—for their sakes and for the sakes of our relationships with our partners, families, friends, and all the creatures we with whom we share this earth.

“I think we could learn something from our pets about handling grief. They are such good caretakers of us in times of sorrow...They do not put time limits on feelings.”

What's your writing process like, and do your pets ever figure into it?

My cats are active writing partners! I usually write in the morning, which is one of their favorite times to play. My writing time is interspersed with crumbling up paper balls to toss at them while I work. Usually one decides to stroll across the keyboard to make some edits. One is usually perched in the window beside me or on a printed poem—drafts make great beds, apparently!

Your debut poetry collection Glass Harvest will be out soon (and I can't wait to read it). Do you have some advice for poets who are trying to complete or publish their first book?

Some of the most bolstering advice I received was from the poet Jane Hirshfield when I took a workshop with her at the Key West Literary Seminar. She said to treat every rejection as a gift of time—time to help the manuscript become its best self. I worked on this manuscript for eight years. It was not always easy to see rejection as a gift; however, when I recall its past selves, I’m incredibly glad they did not get published.

Poetry publishing is all long game. And it can feel even longer when you begin to compare your journey to Poet X or Poet Y. Try not to—or, indulge your envy, let it know you hear it, you understand its fiery pain, then move on. Try to remember comparison is the thief of joy. It is the thief of your very life.

“Try to remember comparison is the thief of joy.”

Fill in the blank: you're stuck on a poem, so you…?

Ignore it. I’m always working on multiple poems at a time, so when one is being disagreeable, I focus on others and let my subconscious chew on the stuck poem awhile. Or, I “break” it, tackling the subject from a different angle, trading narrative for lyric, long for short. I try to notice where my attention drifts and cut those parts. If I’m bored or restless, no doubt a reader is, too.

What is it about the animal world that most captures your attention as a poet?

I love learning about animal societies. I’m working on a poem about albatrosses and discovered that they spend years crafting complex courtship dances. Once they mate, the mates abandon the dance and form a private language, discernible only to each other. This is amazing to me and seems profoundly similar to human partnership: every long-term couple I know also has its own private shorthand.

Advice for poets who want to write meaningfully about the death of their pets but don't want to be dismissed as sentimental?

The advice is the same as what I would give for writing about the grief of losing a beloved human: be concrete. Focus on the specific interactions you have with the pet, the specific expressions of its personality. Don’t be afraid to be humorous. My favorite memory of Stevens is of her lying on my face and neck at 3 a.m., a ball of purring sweetness, while also drooling all over me. Include the drool with the purrs and you’ll be in good shape.

A simile for your cats?

Oh lord, I’m such a poet; my cats’ names are metaphors for themselves.

Chicory is an invasive weed in Illinois where I grew up—incredibly hardy, able to grow along roadsides and in pavement cracks. Chicory the cat is the same—hard to imagine her not thriving wherever she goes.

Sage is much like the spice—unique. Flavorful. And, as with the spice, which I rarely use but love the scent of, I don’t quite know what to do with her most of the time.

Introducing Pet Poetics: An Interview Series with Poets about Their Animals & Art

The interview series Pet Poetics explores the intersection of animals and art.

Let's call this what it is: a mission statement. And an invitation.

I've been toying with the idea of starting a blog for a while now, but you know what? I want to hear what you have to say. Specifically, I want to talk to other poets whose lives and art have been affected by the animals they keep and care for.

My own experience tells me this companionship is profound but often dismissed. I've heard the most big-hearted people say after my dog died that "at least it wasn't a family member." OH REALLY NOW.

Look, I get it. Animals can't talk. They can't write poems. They don't go to their little dog jobs and earn little dog wages and put them in the little dog bank.

But you can't tell me that my dogs haven't played a role in fine-tuning my empathy. You can't tell me they haven't rafted me through some of the lowest points of my life. You can't tell me they aren't family.

So that's what this space is for: to give these relationships the spotlight they deserve and to explore how our animals shape us and our work.

What I Can Promise You

- There will be animal pictures. A lot of them.

- Each interview will be distinct, showcase the poet's unique perspective, and explore their work.

- Poets are welcome to share poems inspired by or about their pets (though not required).

- You'll probably discover some new poets and your life will be better for it.

What I Can't Promise You

- Fame.

- Fortune.

- Eternal life.

Interested?

Get in touch, and we'll nerd out about poems and your pets. I'm excited to hear and share your stories.